Quick Snapshot of the Makonde Carvings, Sculpture and Art

Overview of the Makonde Carvings, Sculpture and Art

The Ruvuma river divides northern Mozambique and southern Tanzania, where Makonde carvings and sculpture artisans and painters create their East African sculptures and modern paintings. Traditional African items and contemporary works of art have been categorized within this subgenre by art historians, dealers, and collectors. There has been at least one known exhibition of Makonde wood carving, sculpture and art in Mozambique’s Centro Cultural dos Novos dating back to the early 1930s.

Categorization of Traditional and Contemporary Makonde Wood Carvings, Sculpture and Art Style

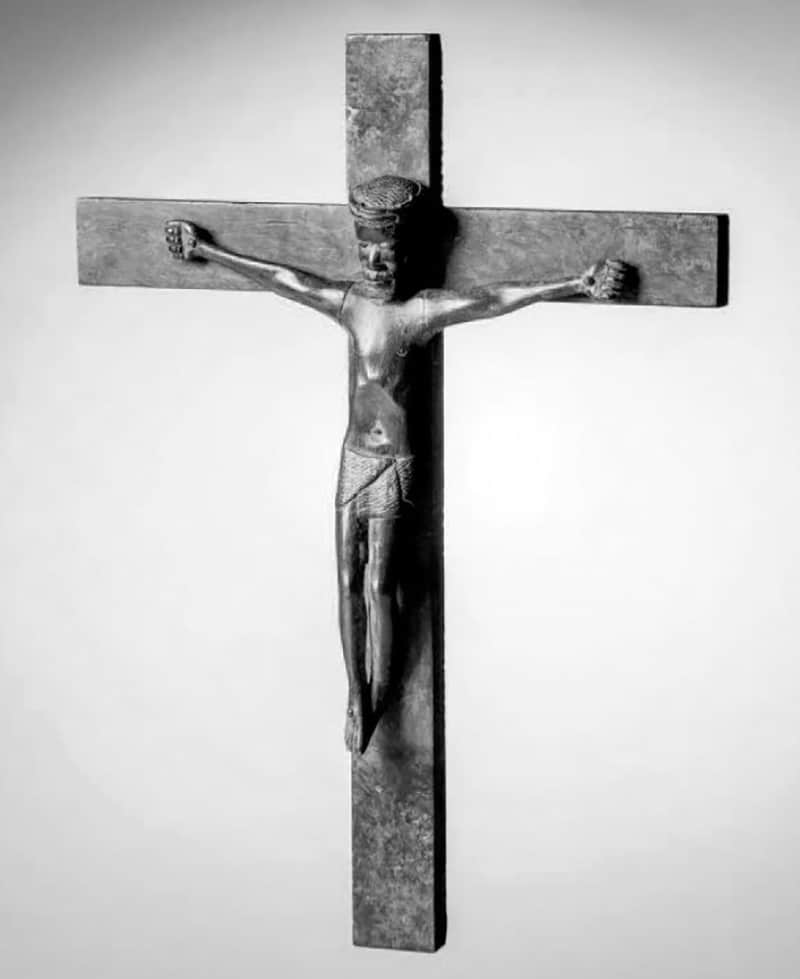

In addition to secular household objects, the Makonde have a long history of creating sacred figures and masks. Colonialists from Portugal as well as from other countries began arriving in the Mueda plateau in northern Mozambique during this time period. Makonde wood carvings piqued their interest, and they ordered a variety of items, from religious to political “eminences.” They decided to use pau-preto (ebony wood, Diospyrus ebenum) and pau-rosa (Swartzia spp.) instead of the previously soft and short-lived wood for the new works after seeing so much interest. When the old Makonde way of life first came into contact with Western culture, it might be said that the classical European style was introduced for the first time.

Known as Modern Makonde carvings, sculpture and art, Tanzania has been cultivating these art categories form since the 1930s. The creation of abstract forms, often representing the evil spirits known as Shetani in Swahili, marked a dramatic break from traditional Swahili sculpture. Master carver Samaki Likankoa created this shetani style in the early 1950s with the help of Tanzanian art curator Mohamed Peera, who played a crucial role in the development of the modern Makonde art movement. It is not uncommon for Makonde sculptors, like George Lugwani, to create works of art that are wholly abstract, lacking any discernible figures. Contemporary African art includes Modern Makonde Art, which has been around since the 1970s. Among these painters, George Lilanga was the most well-known, having begun his career as a carver before transitioning to painting.

A different type of black wood carvings of the Makonde, sculpture and ceremonial art is the Mapiko mask (singular: Lipiko). As far back as the nineteenth century, they have been used in tribal dances preceding coming-of-age celebrations. A single piece of light wood (usually “sumaumeira brava”) was used to meticulously carve these masks, which may depict shetani spirits, ancestors, or contemporary individuals (real or idealized). The dancers either wore the masks on their heads with the mask pointed straight at the audience or bent forward to gaze through the mask’s mouth.

Modern Makonde Carvings Involving Woodcarving and Obsolete Woodworking Techniques in the Twentieth Century

To meet new societal and economic demands, the traditional meaning of this activity began to change after the establishment of road networks by Portuguese forces during World War I. A symbol of ceremonial expression developed by men and kept secret from women, Western influences on Makonde carvings, sculpture and art in general changed who created it and why. Many Makonde were driven to expand their woodcarving techniques due to Portuguese taxation and forced labour. This evolution is depicted in these figures. Crafts such as tools and ritualistic masks have historically been the focus of creation. However, following the construction of roads, Europeans and missionaries began to engage Makonde people to build religious symbols. As a result, Makonde ebony carvings, sculptures and art evolved into three distinct subgenres: Ujamaa, Shetani, and Binadamu.

Branches of Arts the Makonde Culture

Makonde Tree of Life Carving or Its Counterpart Ujamaa

Called the “Tree of Life” because it is rooted in the source of all life, Roberto Yakobo Sangwani escaped Mozambique in the late 1950s and settled in Tanzania. A Makonde art form known as Dimoongo, or “power of strength,” was carried by him at all times. Wrestlers gathering around a victorious champion were showcased in the past. Over time, the central figure came to represent tribal chiefs or other persons standing in solidarity with their neighbours or loved ones. A central figure is depicted in this manner, surrounded and supported by surrounding characters, regardless of the subject matter. This group of people represents the Makonde’s deep veneration for their ancestors and their civilization, as well as their ujamaa (family ties).

Shetani (“Devil” in Swahili) Makonde Carvings – Representations of Makonde Mythology and Spirit

The spiritual dimension is depicted by the use of otherworldly physical qualities, such as large, twisted facial or bodily features, as well as animals. It is thought that Shetani’s essence manifests itself in five forms: human; mammal; fish; bird; and reptile. Culturally significant symbols, such as a mother’s breasts or a calabash, are also included in certain Makonde, carvings, sculptures and art in general.

Binadamu

The Makonde social roles are fully embodied in Binadamu, a naturalistic type. The most common sightings are of men smoking and women doing household chores. The market for Makonde carvings thrived after the Portuguese established contact. They began focusing on their skill and creating representations of Makonde people going about their daily lives to appeal to Western tastes.

Rituals of Passage – Makonde Carvings Value

Before the commercial popularity of Makonde carvings, they were used to depict evil spirits during rites of passage. Getting a man ready for maturity is a big deal since it’s when he gets circumcised. Mapiko, a ritualist dance, is performed at the beginning of this occasion. This dance has three active parts. This young man’s journey into manhood will pit him against the Mashapilo, a malevolent spirit intent on spreading mischief and disrupting health. As well as the dancer wearing a mask impersonating a deceased man who has returned to torture the community. Both of the masked dancers represent the darkness that the boy, who in this day becomes a man, must encounter and defeat in this performance. Mkukomela (or Hammerer), the head of the rite, will then perform the child’s surgery after this dance. Immediately following his circumcision, a boy would be sent to a place called a Likumbi where he would be housed alongside other men and boys for several days. Boys are taught the duties of a man in society while receiving medical treatment. They are learned to hunt and care for the land resulted in a physical shift. A social transformation in the way men are reintegrated into their communities is also taking place. Respect for older people is taught, as well as good sex etiquette and the importance of morality and values. The Likumbi is set ablaze, and the lads are given new names after being healed. However, Makonde carvings in female initiation occurs far later than in male initiation. When a young lady marries, she undergoes a similar transformation through ritualistic dance and solitude. A Makonde woman will go about with a woodcarving doll to induce conception once she is married.

A Collection of Contemporary Makonde Carvings Tanzania

Makonde Binadamu’s sculptural work

The work of Makonde Shetani

Ujamaa sculpture

George Lugwani’s abstract carving in mpingo for the Makonde

Makonde Carvings for Sale

You can find numerous Makonde carvings being sold on various online marketplaces today such as Etsy.com, Ebay and more.

For more articles related to Tanzania arts, click here!