African Wild Dog – Naming, Evolution, Taxonomy and More

Canine from Africa

Africa’s sub-Saharan wild dog (Lycaon pictus) is also known as the painted dog or African hunting dog. Only one extant Lycaon, a hyper carnivorous canine lacking dewclaws and specialized dentition for a hyper carnivorous diet, can be found in Africa. There are 39 subpopulations with a total adult population of 6,600 (1,400 mature individuals), all of which are threatened by habitat loss, human persecution, and disease outbreaks. Since 1990, the IUCN Red List has listed the African wild dog as endangered because its largest subpopulation is expected to be less than 250.

The wild dogs in Africa hunt antelopes during the day, and it does it by pursuing the prey until they run out of energy. It has two natural predators in the wild: lions, who can kill dogs, and spotted hyenas that prey on them.

In common with other canins, the African wild dog regurgitates food for both its young and adults as a way to socialize. Those under age are allowed to eat remains first.

Some hunter-gatherer civilizations, including the predynastic Egyptians and the San, valued this animal even though it was not as well-known in African folklore or culture as other African predators.

Naming

Many more names exist for the African wild dog, like the Cape hunting dog, also referred to as the “painted lycaon,” “painted dog,” “painted hunting dog,” and “painted hunter.” As the term “wild dog” has several negative connotations, some conservation groups are trying to rebrand the species by using the term “painted wolf.” The phrase “African wild dog” is still widely used despite this. A better way to dispel negative stereotypes about the breed has been coined the “painted dog” moniker.

These Indigenous Terms Refer to the African Wild Dog:

Native Linguistic and Indigen

Amharic, & ታኩላ (takula)

Ateso, & Apeete

Damara, & IGaub

isiNdebele, & Iganyana iketsi leKapa

isiXhosa, & Ixhwili

isiZulu, & Inkentshane

Kalenjin, & Suyo

Kibena, & Liduma

Kibungu, & Eminze

Kichagga, & Kite kya nigereni

Kihehe, & Ligwami

Kijita, & Omusege

Kikamba, & Nzui

Kikuyu, & Muthige

Kiliangulu, & Eeyeyi

Kimarangoli, & Imbwa

Kinyaturu, & Mbughi

Kinyiha, & Inpumpi

Kinyiramba, & Mulula

Kisukuma, & Mhuge

Kiswahili, & Mbwa-mwitu wa Afrika

Kitaita, & Kikwau

Kizigua, & Mauzi

Limeru, & Mbawa

Lozi, & Liakanyani

Luo, & Sudhe, prude

Maasai, & Osuyiani

Mandingue, & Juruto

Nama, & Gaub

Pulaar, & Saafandu

Samburu, & Suyian

Sebei, & Kulwe, suyondet

Sepedi, & Lehlalerwa, letaya

Sesotho, & Lekanyane, mokoto, tlalerwa

Setswana, & Leteane, letlhalerwa, lekanyana

Shona, & Mhumhi

siSwati, & Budzatja, inkentjane

Tshivenda, & Dalerwa

Woloof, & Saafandu

Xitsonga, & Hlolwa

Yei, & Umenzi

Study of its Evolution and Taxonomy

The Taxonomy

Oppian characterized the thoa, a hybrid between the wolf and leopard that resembles in both looks and color, as the earliest documented mention of the African wild dog species. An Ethiopian wolf-like creature with a multicolored mane is mentioned in Solinus’ Collea rerum memorabilium, written in the third century AD.

Following a trip to Mozambique, a specimen of the African wild dog was examined by Coenraad Jacob Temminck. He misidentified Hyaena picta because he thought it was a Hyaena. Joshua Brookes gave the Lycaon tricolor its African wild dog scientific name in 1827 after identifying it as a canid. Greek o (lykaios), which means “wolf-like,” is the root of the word Lycaon. The specific epithet pictus (Latin for “painted”) was afterward reapplied in conformity with the International Rules for Taxonomic Nomenclature derived from the original picta.

Because of the serrated canines, paleontologist George G. Simpson classified the African wild dogs as “bush dogs, dholes, and into the subfamily Simocyoninae. Aside from differences in dentition, Juliet Clutton-Brock argued that the three species should not be lumped together as members of a single subfamily.

The Evolution

Regarding coat color, diet, and running abilities for hunting, the African wild dog has the most specialized adaptations of any canid in the world. The loss of the first toe on each of its forefeet enhances its stride and speed. This characteristic makes it easier for the animal to track prey across large land areas. Except for the spotted hyena, it has the largest premolars of any known carnivore. The evolution of the lower carnassial talonid has become an extremely sharp knife, whereas the postcarnassial molar has either diminished or gone. African wild dogs and Dholes, two other hypercarnivores, have adapted similarly. The coat coloration of the wild dogs Africa is one of the most varied of any mammal. Genetic diversity can be seen in patterns and hues unique to each individual. It is possible that these coat patterns could be used for concealment, communication, or temperature regulation. When the Cuon and Canis lineage split from the Lycaon lineage 1.7 million years ago, this set of adaptations splintered the gigantic ungulates, according to a study published in 2019.

Israel’s HaYonim Cave recently yielded an ancient pictus fossil going back more than 200,000 years. We don’t know much about the African wild dog’s evolution because there aren’t many fossilized remains. According to some experts, the canis subgenus Xenocyon may have been the ancestor of both Lycaon and Cuon, which thrived in Eurasia and Africa throughout the Early and Middle Pleistocene periods. Xenocyon could be renamed Lycaon, according to specific other theories. Although the African wild dog’s first metacarpal (dewclaw) was removed from Canis (Xenocyon) Falconeri, its dentition remained largely unspecialized. As a result, one academic disregarded this connection. Falconeri’s lack of a metacarpal is a poor indicator of its closeness to the wild dog Africa, and its dentition was too distinct from inferring ancestry.

The Plio-Pleistocene L. is another potential for ancestry. It is based on the existence of accessory cusps on the upper and lower premolars of the sekowei of South Africa. Lycaon, the only living canid with these adaptations to a hyper carnivorous diet, is the only canid with these traits.

The first metacarpal of L’s sekowei had not yet been lost. pictus had more prominent teeth and was more robust than the current species.

Between 1.7 and 1.74 million years ago, the wild African dog split from other canid lineages, and it is now thought to be genetically isolated from all other canid species.

Mingling With the Dhole Species

Dhole (Cuon alpinus) and African wild dog (Canis lupus familiaris) genome sequencing were performed in 2018. There was a lot of indication that they had interbred in the past. Although its current ranges are separate, the dhole may have been found throughout Europe during the Pleistocene. According to their findings, researchers believe that the dhole was once a native of the Middle East, where it may have interbred with wild dogs African in North Africa. In the Middle East and North Africa, there is no evidence that the dhole existed.

African Wild Dog Subspecies

In 2005, the following MSW3 subspecies were identified:

The L. p. pictus Temminck, 1820 or Cape wild dog: A Cape wild dog that was captured and brought back to the Cape; aside from being the heaviest, the nominated subspecies are also the largest. Even within the same subspecies, there are geographic variations in the coat color: Cape specimens are distinguished by a large amount of orange-yellow fur overlapping the black, the partially yellow backs of the ears, the predominantly yellow underparts, and a few whitish hairs in the throat mane. As a result of the nearly equal growth of yellow and black on both the upper and lower body, the Mozambique form is distinct from the Cape form.

This is a list of Other Synonyms: Matschie, 1915; Gobabis, windhorni, zuluensis, and lalandei, Brookes, 1827; tricolor, A. Smith, 1833; typicus, Burchell, 1822; venatica, are all synonyms of cacondae (Thomas, 1904).

The L. p. Lupinus Thomas, 1902 or East Africa wild dog: The coat of this subspecies is exceptionally dark, with only a tiny amount of yellow.

This is a list of Other Synonyms: “kondoae,” which appears in the “Matschie, 1915” entry for “kondoae,” along with “gansseri,” “hennigi,” “huebneri,” “lademanni,” “langheldi,” “pragari,” “Matschie, 1912,” “richteri,” “ruwanae,” “ssongaeae,” “stierling.”

The L. p. somalicus Thomas, 1904 or Somali wild dog: subpopulation

Compared to the East African dog wild, this subspecies has shorter and rougher fur and weaker teeth. It has buff-colored yellow sections and resembles the Cape wild dog in appearance.

This is a list of Other Synonyms: referring to the 1915 term “luchsingeri,” one might also use the terms “matschie,” “rüppelli,” “takanus,” and “zedlitzi,” all of which were coined by Matschie, 1915.

The L. p. sharicus Thomas and Wroughton, 1907, also known as the Chadian wild dog, isbrightly colored with 15mm hair.

Brain cases outnumber L.p. pictus.

Other Synonyms: Matschie, 1915; ebermaieri.

The L. p. manguensis Matschie, 1915, West African wild dog: There is a subspecies of wild dogs found in West Africa. The West African wild dog roamed the continent from Senegal to Nigeria. Today, there are only two subpopulations, one in Senegal’s National Park of Nikolo-Koba and the other in Burkina Faso, Benin, and Niger. Only 70 adults of the west African wild dog are believed to be left in the wild.

Other Synonyms: are “mischlichi,” (Matschie, 1915).

Despite the species’ genetic richness, these subspecific names are not widely accepted. For a long time, it was assumed that the wild dog populations of East Africa and Southern Africa were genetically distinct because of the small sample sizes. East African and Southern African people interbred significantly in the past, according to a new study with a larger sample size. There is a transition zone that includes Zimbabwe, Botswana, and southeastern Tanzania between the populations of southern and northeastern Africa with unique nuclear and mitochondrial alleles. West African wild dogs may have a distinct haplotype, making them different subspecies. Painted dog genotypes may no longer exist in the original populations of painted dogs in the Serengeti and Masai Mara.

Africans Wild Dog Characteristics

The African wild dog has the most robust build compared to the other African canids. At the shoulders, the species stands 60 to 75 centimeters (24″ to 30″) tall, measures 71.2 centimeters (28.4″ to 44″) long, and has a 29.4 centimeter (1.2″) to 1.12-centimeter-long tail (11 to 16 in). Adults weigh between 18 and 36 kg (40 to 79 lb). East African dogs typically weigh between 44 and 55 pounds, whereas, in southern Africa, males averaged 32.7 pounds and females 24.5 pounds (54 lb). The grey wolf species complex is the only living canid greater than them in terms of body mass. Females are typically 3–7 percent smaller than males on average. With large ears and no dew claws, the African wild dog is a distinct species from other members of the Canis family. The middle two toepads are usually joined together. Due to the degeneration of the final lower molar, short canines, and massive premolars (the most significant relative to body size of any carnivore except hyenas), its dentition differs from that of Canis. One blade-like cusp atop the lower carnassial M1 boosts teeth shearing capacity and, subsequently, prey consumption rate.

The Asian dhole and the South American bush dog both have what’s known as a “trenchant heel.” When compared to other canids, the skull is narrower and broader.

Unlike other canids, the African wild dog has solely bristle hairs with no underfur, making it unique among canids. It gradually loses its fur as it ages, with older individuals almost uncovered; African wild dog canines can distinguish each other from 50 to 100 meters away because of their extreme color variety. There are found in the northeastern part of the continent and those found in southern Africa. Coat patterns are concentrated on the trunk and legs of this species. Face markings are sparse; the black muzzle fades into brown on the cheeks and forehead as the animal matures. Behind the ears, a brownish-black line runs from the top of the head to the brow. A few have a teardrop-shaped brown mark under their eyes. On the rear, the head and neck are brown or yellow. Sometimes, a white patch occurs behind the forelegs, while others have white chests and throats. The tail is usually white at the tip, black in the middle, and brown at the base. Some versions are entirely devoid of white, while others have a black undercoat beneath them. Sometimes the left and right sides of a dog’s body have unique patterning on their coats.

Behaviors

Societal and Sexual Behavior

Living and hunting alone are pretty rare in this species. It is a social animal; it lives in groups of two to twenty-seven adults and puppies raised year-round. Packs of four or five adults are standard in Kruger Park and the Masai Mara, whereas groups of eight or nine adults in Moremi and Selous are common. Springbok herds in Southern Africa’s huge herds may have spawned temporary aggregations involving hundreds of individuals. When it comes to power dynamics, African wild dog males and females follow different hierarchies. The oldest male may lead a pack, but a younger male may replace him. As a result, some groups have former pack leaders who are now elderly. The dominant pair generally dominate reproduction. Males of this species remain in the natal pack, whereas females disperse, unlike most other social animals (a pattern also found in primates such as gorillas, chimpanzees, and red colobuses). It is common for men to outweigh women 3:1. To reduce inbreeding and allow the evicted individuals to locate new packs and breed, dispersing females join other groups and eject some residents tied to other pack members. When a group of males decides to disband, the other packs that already contain males will almost always reject the newcomers. Despite being the most social canid, the African wild dog lacks the grey wolf’s facial expressions and body language. This is most likely because the social organization of the African wild dog is less hierarchical. On the other hand, African wild dogs do not require complicated facial expressions to repair family connections after a long separation, unlike wolves.

East African wild dog population appears to have no defined breeding season, whereas people in Southern Africa typically breed between April and July. A solitary male escorts the female during estrus to keep other members of the same sex away. The African wild dog lacks or has a highly brief copulatory tie (less than one minute) compared to other canids, possibly due to the availability of larger predators in its region. It takes an average of 12–14 months between pregnancies. Litter sizes range from six to sixteen pups, indicating that a single female can produce enough offspring each year to form an entirely new pack of African wild dogs. Breeding is strictly limited to the dominant female, who may murder the pups of subordinates if she cannot gather enough food to maintain more than two litters. After giving birth, the mother stays in the cave with the puppies while the rest of the pack goes hunting. Until they can eat solid food, she usually prevents pack members from getting near the puppies until they are about three or four weeks old. Pups are taken out of the den and fed in the open air for about three weeks, weaned from their mothers at five weeks, and fed meat that the rest of the pack has regurgitated. A noticeable lengthening begins at seven weeks in the puppies’ legs, muzzles, and ears. During the first eight to ten weeks of their lives, puppies are taken on hunts by their parents. After a year, the youngest pack members lose the right to eat kills before the rest of the pack.

The Ratio of Female to Male

Males outnumber females in African wild dog packs. Males tend to stay with the group while their female pups disperse, which is corroborated by a shifting sex ratio in succeeding litters. A more considerable proportion of African wild dog males are born in the first litters, and the balance of males to females in the following is skewed even more toward the females as the females get older. The earlier litters produce more stable hunters, while the higher ratio of female dispersals prevents packs from growing too large.

“Sneezing” and “Voting” are Two Ways to Communicate

African wild dog populations in the Okavango Delta have been “rallying” before hunting. The likelihood of a departure rises as more dogs “sneeze,” however, this does not happen at every rally. A fast exhalation via the nose distinguishes these sneezes from others. The group is more likely to disperse if the dominant mating partners sneeze first. After three sneezes, the dog will be expelled from the situation. Sneezing signals a pack is ready to go on the hunt when at least ten of its members likewise sneeze. Researchers assert that wild dogs in Botswana “use a specific vocalization (the sneeze) along with a variable quorum response mechanism in the decision-making process.

Avoidance of Inbreeding

Since the African wild dog population is small and dispersed, it is at risk of extinction. The ability to avoid inbreeding by selective mating is a defining characteristic of the species and can potentially have substantial implications for the population’s survival. Within the natal packs, inbreeding is extremely rare. Natural selection may have favored inbreeding since it leads to the manifestation of recessive deleterious genes. Populations that refuse to engage in incestuous mating will go extinct within the next century, according to computer simulations. As a result, decreasing numbers of potential unrelated mates will likely have substantial demographic effects on the long-term survival of tiny wild dog populations.

Conduct While Hunting and Feeding

Medium-sized common antelopes are the African wild dog’s favorite prey item. All African big diurnal predators, save for cheetah, are found in this region. The African wild dog stalks its prey for up to 60 minutes at speeds of up to 66 kilometers per hour to catch it (41 miles per hour). To stop a large target, it is bitten repeatedly on the legs, abdomen, and rump until it stops moving. Minor game is dragged down to the ground and torn apart.

The hunting strategy of African wild dogs varies depending on the type of prey they encounter. It is common to go after antelopes while they protect themselves by sprinting in enormous circles to prevent their game from fleeing. Larger prey, such as wildebeest, can take up to thirty minutes to bring down, although medium-sized wildlife usually takes two to five minutes. Male African wild dogs are typically responsible for snaring dangerous creatures like warthogs by the snout.

Wild African dogs can be successful in their hunts up to 90 percent of the time, depending on prey type, forest cover, and pack size. Despite their diminutive stature, African wild dogs outcompete lions and hyenas in terms of kill success (27–30%) and prey consumption (25–30%). When six wild canines from Okavango National Park went on 1,119 chases, just 15.5% of them managed to bring down prey on their own. The benefit-to-cost ratio for each dog is excellent because the kills are shared.

Prey, like mice, hares, and birds are hunted individually, but more dangerous animals like cane rats and porcupines are killed with a quick, well-placed bite to avoid harm. Small prey is eaten entirely, whereas large animals are stripped of their meat and organs while preserving their skin, skull, and skeleton. Within fifteen minutes, a group of African wild dogs can finish off a Thomson’s gazelle. Africa’s wild dogs eat between 1.2 and 5.9 kilograms (2.6 and 13.0 lb) each day, with packs of 17 to 43 individuals in East Africa slaying an average of three prey items per day.

In contrast to most social predators, African wild dogs of Africa puke food for adults and children. Subordinate adult canines assist in feeding and protecting pups, even if they are not yet old enough to eat solid food.

Ecology of The African Wild Dog

African Wild Dog Habitat

There are few forests in the African wild dog’s natural habitat. This propensity is most likely due to the animal’s hunting habits, which necessitate a clear line of sight and an unhindered path. However, it can be found roaming through woodlands, shrubs, and mountains in quest of food. The Harenna Forest, a wet montane forest up to 2,400 m (7,900 ft) in the Bale Mountains of Ethiopia, is home to a colony of African wild dogs. There has been at least one documented sighting of a rucksack on the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro. Wild dog bands have been sighted at altitudes ranging from 1,900 to 2,100 m, and a dead one was found in June 1995 on the Sanetti Plateau (13,290 ft) at 4,050 m. In Zimbabwe, the species has been documented at 1,800 m (5,900 ft).

Diet – What Do African Wild Dogs Eat?

The African wild dog diet consist of mostly five species as prey when available, according to an extensive study across all species: the greater kudu; the Thomson’s gazelle, impala; the Cape bushbuck; and the blue wildebeest. Thomson’s gazelle is its most common prey in East Africa, while impala, reedbuck, kob, lechwe, and springbok are its favored prey in Central and Southern Africa. Insects and cane rats are among the many creatures that can be found in the area. Other regional studies indicate the maximum prey weight is between 90 and 135 kilograms, which is higher than the typical range of 15 to 200 kilograms (33 to 441 pounds) (198 to 298 lb). Larger animals, such as kudu and wildebeest, are predominantly, but not exclusively, hunted for their calves. Serengeti zebras can weigh up to 240 kilos, and numerous African wild dog groups specialize in pursuing them (530 pounds). Separate studies suggest that some prey on a target weighing as much as 289 kg (637 lb). Bat-eared fox carcasses were rolled on by one pack before they were eaten. African wild dogs have occasionally found the carcasses of spotted hyenas, leopards, cheetahs, and lions caught in traps.

Opponents and Rivals

Adult and child deaths in African wild dogs are primarily caused by lions, which predominate the species. African wild dogs have a low population density in areas with a high concentration of lions. Lions decimated Etosha National Park’s reintroduced pack. During the 1960s, the Ngorongoro Crater saw an increase in African wild dog sightings due to a decrease in lion populations. However, the lion population rebounded, and the number of African wild dogs decreased. This shows that lion pride’s dominance is more competitive than predatory, as giant predators such as dogs are often killed and left unconsumed.

On the other hand, African wild dogs have been known to attack older or injured lions. Wild dog packs have been seen to effectively protect their members against assaults by lone lions on occasion. At an impala kill site in March 2016, safari rangers witnessed a pack of lions and subadult dogs engaged in an “unbelievable struggle” with an adult lioness that had attacked a subadult dog, even though the subadult dog had been killed. An adult male dog was rescued from a lion assault by a gang of four wild dogs, who ferociously defended him.

Known as essential kleptoparasites, spotted hyenas target African wild dogs’ prey. It is not uncommon for them to investigate areas where African wild dogs have rested and eat any food remains they come across. Even though they run the risk of being surrounded, lone hyenas approach gingerly and try to steal a chunk of meat from an African wild dog kill. There is an advantage to acting in groups for spotted hyenas when taking African wild dog kills, but this is offset by the fact that the latter are more likely to cooperate than the former. In Africa, spotted hyenas are rare food sources for African wild dogs. The relationship between African wild dogs and hyenas is beneficial to the hyenas, with a negative association between the density of African wild dogs and hyena numbers. African wild dogs have been known to be killed by spotted hyenas in addition to acts of piracy. While Nile crocodiles may occasionally and opportunistically prey on a wild dog in Africa, African wild dogs are apex predators and often lose to larger social carnivores. Giant eagles like the martial eagle can prey on young African wild dog puppies when they emerge from their dens.

Distribution

Most sub-Saharan Africa was originally home to African wild dogs, excluding the aridest desert regions and lowland forests. Nearly extinct in North and West Africa, the species’ population in Central Africa and Northeast Africa has been dramatically reduced during the last few decades. Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe hold most of the species’ present population in southern and east Africa. Habitat loss has made it difficult to know where and how many there are.

North Africa Region

Any remaining populations of the African wild dog in North Africa are likely to be genetically distinct from any other L.pictus, hence having a high conservation priority.

Algeria: Although L.pictus is likely extinct locally, there may be a relict population in the southern part.

Its Distribution: Only the Teffedest Mountains in Scotland have recently been reported as having this species. Due to Tuareg tribe members’ trapping and poisoning, the species in Mouydir Arah Mountains is possibly gone. The last sighting in the Ahaggar National Park occurred in 1989.

Mauritania: It is pretty unlikely of any to be present here.

Its Distribution: Hunters in Western Sahara’s coastal region reported seeing a pack of wild dogs in 1992, but no one knows what species they are. Thirty years earlier, they had witnessed one.

West Africa Region

Senegal’s Niokolo-Koba National Park, where the species is struggling throughout most of West Africa, reports African wild dogs in Guinea, Senegal, and Mali.

Benin: L.Pictus is most likely extinct in the country, according to a 1990 poll that found that people doubted the species’ continued existence.

Its Distribution: Parc W may be home to the country’s final L. Notwithstanding the belief that pictus populations were declining or extinct in 1988, In Pendjari National Park, its number may be dwindling.

Burkina Faso: L.Pictus is likely extinct in the surrounding area, despite the species’ protected status, due to widespread poverty.

Its Distribution: In 1985, the Nazinga Game Ranch in Namibia reported a record of the animal. Arli National Park and the Comoé Province may have a few left.

Gambia: In 1995, the species was last seen near the Senegalese border.

Its Distribution: The Senegalese border region has a small population.

Ghana: Despite L.pictus being legally protected, it is on the verge of extinction in the wild due to widespread poaching and unfavorable cultural attitudes toward predators.

Its Distribution: Despite the lack of recent observations, the African wild dog species may still be extant in Bui and Digya National Parks. L. has been sighted by hunters. An unusual sighting of a pictus at Kyabobo National Park

Guinea: Despite its status as a protected species, the L.pictus population is in terrible shape.

Its Distribution: In Senegal, the species can be found in the nearby Niokolo-Koba National Park, which is in Badiar National Park. In 1991, three cows perished in the Ndama Fôret Clasée of the Sankaran River after being infected by the species.

Ivory Coast: There have been only a few documented sightings of this species, and most people have never heard of it. In addition, it is referred to as “noxious” in the legal system.

Its Distribution: The species was last observed in the late 1980s in Comoé National Park and Marahoué National Park, but it may still be the last sightings that occurred during the 1970s.

Liberia: No mention of L.pictus is found in Liberia’s folklore. There is no evidence of pictus in the region, indicating that the species was probably extinct or never there.

Its Distribution: The African wild dog species may have once been found in the north but is now extinct.

Mali: L.pictus, which was once omnipresent, has fallen out of favor.

Currently, pictus is a rare occurrence in Mali. When a ground survey was conducted in the 1980s, the species was noticeably absent despite being discovered in the Forêt Classée de la Faya in 1959.

Its Distribution: Senegal and Guinea border regions in the south and west of the country may still be home to the species.

Niger: The species is almost extinct in its natural habitat due to eradication efforts in the 1960s. Despite legal immunity on L.pictus, as recently as 1979, game guards were still shooting pictus specimens. It is unlikely that the species will be able to survive in the face of periodic droughts and a lack of prey.

Its Distribution: Small populations of pictus may persist in northern areas like Parc W and the Sirba region.

Nigeria: Despite the occasional presence of pictus vagrants from neighboring countries, Nigerian pictus populations aren’t indigenous. Protective measures for the species have been inadequate, and prey numbers have decreased significantly.

Its Distribution: Even though no sightings were documented between 1982 and 1986, pictus may still survive in tiny numbers in Gashaka Gumti National Park, which is close to Cameroon’s Faro National Park.

Pictus has been sighted in Chingurmi-Duguma National Park on a few occasions, the most recent of which was in 1995. The African wild dog species hasn’t been seen in the area since the 1980s because of rampant poaching in Kainji National Park and Borgu Game Reserve. Extinct since 1978, it was last seen in Yankari National Park. Lame Burra Game Reserve only had one confirmed sighting of one individual in 1991.

Senegal: As a result of only having limited protection, L.pictus in and around Niokolo-Koba National Park’s pictus population has grown significantly during the 1990s, giving Senegal the best opportunity for the species’ survival in West Africa’s west.

Its Distribution: Niokolo-Koba National Park’s pictus population is growing and spreading outward. It was believed that between 50 and 100 lived in the park in 1997. The IUCN’s Canid Specialist Group collaborates with Senegal’s Licaone Fund to monitor and study this population. From 2011 to 2013, environmentalists in Niokolo Koba National Park, Senegal, photographed and tracked wild dog footprints to confirm their continued presence.

Sierra Leone: The species is almost certainly gone in Sierra Leone.

Its Distribution: The people of northern savannah-woodland regions, where they have names for the species and where it may have once inhabited, have reputations for pictus. There have been unsubstantiated sightings in the 1980s. Outamba-Kilimi National Park may have a tiny population, although only one unconfirmed observation has been made.

Togo: Despite receiving only a tiny amount of protection, it continues to thrive, and lack of prey means that pictus is most likely extinct in the country.

Its Distribution: Small quantities of it can be found in the Fazio Mafakasa National Park in the Fazio Islands. Speculation is rife about the existence of a baby L.pictus images taking refuge in caverns on the mountains of Kpeyi, Mazala, and Kibidi’s slopes.

Central Africa Region

The African wild dog species is extinct in Gabon, the Congo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Only in Cameroon and CHAD are these populations still thriving.

Cameroonian nation: However, Cameroon is the only sustainable sanctuary for the African wild dog in Central Africa, along with the Central African Republic and southern Chad. The status of the dog is unknown. African wild dogs do not exist in rainforest reserves, where most conservation efforts have been concentrated. There were some attempts to fix this in the 1990s. There are still strong feelings against the species, as evidenced by the deaths of 25 animals in 1991–1992 in northern Cameroon by professional hunters and the shooting of 65 animals by the government from December 1995 to May 1996.

Its Distribution: Although four packs were documented there in 1997, the species is still commonly seen in and around the Faro National Park. The location between the two national parks where was repeatedly seen in 1989. Bouba Njida National Park is where the African wild dog was spotted numerous times in 1993. The Benue Complex in northern Cameroon was the site of recent research in 2012; however, no wild dogs were discovered most populous country in Central Africa.

Central African Republic: African wild dogs face extinction despite being legally protected.

Its Distribution: Even in 1992, sightings of the African wild dog were documented in the St. Floris National Park near Manovo-Gouda St. Floris. There were only two reported sightings in the Bamingui-Bangoran National Park and Biosphere Reserve in the 1980s, although it was previously reported as a common sight. The Chinko-Mbari river basin in the south of the Central African Republic was spotted with African wild dogs in 2013. Between 2012 and 2017, the number of wild dogs in the Central African Republic (CAR) decreased due to direct pastoral slaughter.

Chad: There have been no recent sightings of African wild dogs, and the legal status of the species remains a mystery. South Africa’s wild dog populations may be linked to those in Cameroon and the Central African Republic (CAR) in the country’s southern region.

Its Distribution: Rare in the 1980s, the Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim Faunal Reserve has not had a sighting of the species since. This species has been declared extinct by the Bahr Salamat Fauna Reserve. It was common in Manda National Park and the Siniaka-Minia Faunal Reserve in the 1980s, but there have been no recent sightings.

Republic of Congo: The African wild dog hasn’t been seen in the Republic of the Congo since the 1970s, despite having complete legal protection.

Its Distribution: As a predator of cattle, the species may have formerly been found in the protected area of Odzala National Park, but the local pastoralists have since exterminated it.

DR Congo: The population of African wild dogs that once thrived in the Democratic Republic of Congo is likely extinct by the late 1990s.

Its Distribution: This species was last spotted in Upemba National Park in 1986.

Equatorial Guinea: In Equatorial Guinea, the species has vanished.

Its Distribution: Bioko and Ro Muni have no records of the species.

Gabon: The African wild dog appears to be extinct at this time.

Its Distribution: The African wild dog species was previously found in Petit Loango National Park but hasn’t been seen in years.

Eastern Africa Region

Due to the disappearance of the African wild dog in Uganda and much of Kenya, its range in East Africa has been reduced. Southern Ethiopia, South Sudan, northern Kenya, and maybe north Uganda have a sparse population. The species is most likely extinct in Rwanda, Burundi, and Eritrea, but it may still be found in small numbers in southern Somalia. Southern Tanzania, on the other hand, is home to some of Africa’s most significant populations of African wild dogs, particularly in the Selous Game Reserve and Mikumi National Park.

Burundi: 1976 marked the year that the species was officially declared extinct.

Its Distribution: No species records have been found within Kibira and Ruvubu National Parks, and the remaining habitats are insufficient to support the species.

Djibouti: The status is unknown.

Its Distribution: The single protected area, Day Forest National Park, is unlikely to be a refuge for this species.

Eritrea: Species are most likely extinct.

Its Distribution: Species were once found in several distant locations, including the Yob Wildlife Reserve, but there have been no current sightings.

Ethiopia: Despite extensive legal protections and the government’s efforts to expand its network of protected areas, the African wild dog is still extremely rare in Ethiopia. Even though the species is now extinct in three national parks, it can still be found in the southern part.

Its Distribution: Gambela National Park used to have regular sightings of the African wild dog species, but the last time anyone saw one was in 1987. The Omo and Mago National Parks are the most common places to visit, with the most recent sighting occurring in 1995. In 1992 and 1993, Omo had one or two packs, and Mago may have as many as five. Bale Mountains National Park is plagued with rabies and shepherd intimidation, making it difficult to do research. Awash and Nechisar National Parks have both reported a few sightings as well. The Yabelo Wildlife Sanctuary was home to three specimens in 1996. Outside of protected regions, the species has been documented.

Kenya: Despite its extensive presence, the African wild dog is only partially protected by law and is most commonly found in areas with low people density. Only 15 African wild dog packs survived in the country as of 1997. Locals have a wrong opinion of it, and it is routinely shot in cattle ranching areas.

Its Distribution: The southern part of Lake Turkana National Parks and the neighboring Turkana County has seen a few sightings. Strays are frequently seen along the Sudanese border between Mandera, Wajir County, and Marsabit National Park. It hasn’t been seen in Buffalo Springs or Samburu National Reserves since the mid-1980s. Observations of it in the Kora National Reserve occurred twice in the years 1982–1983. It was said to be abundant on Mount Kenya in the 1950s, but currently, it is nowhere to be found. A fence erected to protect rhinos in Lake Nakuru National Park means that the species has no chance of recolonizing the area. Despite being frequently shot and trapped inside the Nairobi National Park, it was only seen twice outside of it. In 1991, an outbreak of disease caused the species to disappear from the Maasai Mara. Rift Valley Province and Tsavo National Parks may still be home to it. Only a few packs remained until 2017, when massive unlawful encroachment by cattle herders resulted in the animals being either shot or infected by domestic dogs, resulting in their demise in Laikipia.[81] The Tana River Primate Reserve may also be gone. With the probable exception of a handful of individuals, it is now thought to be extinct in the area.

Rwanda: Despite being officially protected, the African wild dog has gone extinct in Rwanda, most likely due to a disease outbreak. As a result of the commencement of the Rwandan Civil War in 1989, an attempt to recolonize the country was put on hold due to the country’s unsuitability for further recolonization.

Its Distribution: Akagera National Park was once referred to as Le Parc aux Lycaons due to its species abundance. This population was wiped out by a disease outbreak in 1983–1984.

Somalia: In the ongoing Somali Civil War, deforestation, poaching, drought, and overgrazing have rendered the prospects for the African wild dog in the country extremely grim, even though it is protected by law.

Its Distribution: Recently, the African wild dog has been seen in Istanbul-Kudo, Manaranni-Odow, Hola, Wajir, Yamani, and Manarani during the rainy season (both in 2015 and 2016).

The species may still exist in the northern hemisphere, but the last confirmed sighting was in 1982. The Buloburde District had a lot of it up until the late 1970s. Around the Jubba River, a population drop is possible. Somalia’s Lag Badana National Park may be the most fantastic place to see these wolves, as a single group was observed there as early as 1994.

Sudan: During the Second Sudanese Civil War, the African wild dog population decreased considerably, as with all large carnivore species. Despite this, sightings in South Sudan have been documented.

Its Distribution: However, there have been no current updates, and the African wild dog species has not been given legal protection in the Sudd region. The Banggai Game Reserve may be home to it. It was said that a pack of wolves was seen at Dinder National Park in 1995.

South Sudan: Images of African wild dogs captured by camera traps in South Sudan’s Southern National Park in April 2020 have been noticed.

Tanzania: Africa’s wild dog is in a good position in Tanzania, where hunting is prohibited, and the species is protected by law. Tsetse flies, which prevent human settlement in the south, provide an ideal habitat in the south. Rare populations can be found only in Selous Game Reserve and maybe Ruaha National Park, two of Africa’s most important wildlife refuges.

Its Distribution: The Selous Game Reserve has a large species population; in 1997, there were estimated to be 880 adult animals. Mikumi National Park and other nearby areas have also been sighted. In late 1990, only 34 African wild dogs were found in Serengeti National Park, indicating that the species may no longer exist in the park. They are rarely seen in the gardens of Kilimanjaro and Arusha.

Uganda: A resident population of African wild dogs in Uganda seems highly unlikely, given the vigorous persecution of the species following a 1955 command to shoot it on sight. Invasive species have occasionally made their way into the country via Tanzania and South Sudan.

Its Distribution: Observations in scattered areas suggest that the African wild dog may be making a comeback in Uganda, despite a survey undertaken between 1982 and 1992 indicating that the animal was likely extinct in Uganda. One-person bands were found in Murchison Falls National Park in 1994, whereas small packs were found in the Northern Karamoja Controlled Hunting Area the year before.

Southern Africa Region

Many healthy populations of African wild dogs can be found throughout Southern Africa, but northern Botswana, northeastern Namibia, and western Zimbabwe regions are home to one such population. Kruger National Park in South Africa is home to about 400 animals. Kafue National Park and the Luangwa Valley are home to large colonies in Zambia. However, the species is rare in Malawi and probably extinct in Mozambique.

The Angolan Republic: Since 1990, just a few sightings of the African wild dog have been reported, even though the species is protected by law in Angola.

Its Distribution: By the mid-1970s, the species’ numbers had plummeted across Angola’s protected areas, where it thrived once. In 2020, researchers found conclusive evidence that wild dogs are resident and breeding in Bicuar National Park and are present (but potentially just transiently) in western Cuando Cubango province (where vagrants from Zambia and Namibia may come).

Botswana: African wild dogs are most likely to be found in the north of Botswana; hence the outlook for this species in Botswana is positive. Despite this, farmers can shoot it in self-defense with little protection.

Its Distribution: Chobe National Park and the Okavango Delta make up the bulk of Botswana’s Ngamiland, which is also home to the Moremi Game Reserve. A total of 42 packs totaling 450–500 people were thought to reside in the area by 1997. Other regions don’t have the African wild dog.

Malawi: Despite its extreme rarity, government hunters and private individuals with ministerial approval are the only ones allowed with African wild dogs. Kasungu National Park was a frequent spot to see in the 1990s.

Its Distribution: Throughout 1991, there were 18 reports from Kasungu National Park, where the species was frequently seen in the 1990s. Only a few individuals can be found in Nyika National Park and Mwabvi Wildlife Reserve.

Mozambique: For African wild dogs, the future seems bleak in Mozambique. There was a steep drop in this species’ numbers following the 1975 Mozambican War of Independence, and by 1986 it was on the verge of extinction. However, Kruger National Park in South Africa is a common entry point.

Its Distribution: It is currently extinct in western Manica, critically endangered in Tete and Zambezi, and completely extinct in Nampula, where the African wild dog was once widely distributed. In 1996, people in Cahora Bassa noticed a family with pups. After a long hiatus, fourteen animals from Gorongosa National Park in South Africa were successfully reintroduced in 2018.

Namibia: The species is protected by law and is thriving in the northeastern part, despite intensive farmer persecution.

Its Distribution: The species is only known to exist in the northeastern part due to its extinction elsewhere. Those in the northeast are probably linked to those in the Botswana north.

South Africa: Kruger National Park is home to a population of pictus that is “specially protected,” with 350 and 400 specimens in the mid-1990s. After multiple failed restoration efforts, two colonies that grew due to those failed attempts were still not viable.

Its Distribution: The Northern Cape, Kruger National Park, and KwaZulu-Natal are the three main areas where the African wild dog species can be found. It is estimated that between 375 and 450 people live in the Kruger National Park, but they are frequently attacked by lions and other predators and shot or trapped outside the park’s borders. Even though Madikwe Game Reserve could not support a large population in the 1990s, six specimens were released into the reserve. KwaZulu-Natal, where it was reintroduced in the early 1980s, is the only place where the species may be found. Reintroduction has resulted in a broad spectrum of attitudes, from hostile to supportive.

eSwatini: It appears that the country has no permanent residents.

Its Distribution: A troop of African wild dogs was observed murdering a blesbok in December 1992 before fleeing the area two weeks later.

Zambia: Despite its long history of persecution, the animal is now fully protected under Zambian law and may only be hunted with costly permission obtained from the Minister of Tourism himself. pictus is still common and may be found in most large protected areas with adequate habitat and prey. But since 1990, there has been a decline.

Its Distribution: There have been no reports of this species in Lusenga Plain National Park since 1988, when it was last seen in falling numbers. Sumbu National Park has reported sightings of the animal, possibly on the decline due to sickness; North Luangwa National Park and the nearby Musalangu and Lumumba Game Management Areas had minimal populations in 1994. Anthrax had already decimated its numbers in the South Luangwa National Park. The Lupine Game Management Area, the Luambe National Park, the Lukusuzi National Park, and the Lower Zambezi National Park have all reported sightings.

Zimbabwe: According to estimates, 310 and 430 African wild dogs lived in Zimbabwe in 1985. A survey conducted between 1990 and 1993 estimated the population at 400–600 animals, indicating a growth during the 1990s. The species is legally protected and can only be hunted once, between 1986 and 1992, with a permit.

Its Distribution: Wild dog populations are concentrated in and around Hwange National Park, the Matatusi and Deka Safari areas of Zimbabwe, and the Kazuma Pan National Park in Zimbabwe. A total of 35 packs, each holding 250–300 individuals, are thought to live in these areas.

Threats – Are African Wild Dogs Endangered?

The African wild dog population has shrunk from 160 to 26 since 2012 due to human-wildlife conflict, illness transmission, and high mortality rates in the Chinko region of the Central African Republic (CAR). Similarly, pastoralists from the Sudanese border region brought their livestock into the area. Rangers seized large quantities of poison and found numerous lion carcasses in the encampment of livestock herders. Members of the vast herbivore poaching trade, the sale of bushmeat, and the traffic in lion skins accompanied them.

Historically

Egypt Civilization

Order triumphed over disorder and the transition from the wild to the domestic dog, as depictions of African wild dogs on Egyptian cosmetic palettes and other artifacts from the predynastic period suggest. In addition to wearing the tails of African wild dogs on their belts, as seen on the Hunters Palette, predynastic hunters may have felt a strong affinity for the African wild dog. Pictures of African wild dogs were significantly less common throughout the Dynastic period, and the wolf took on the animal’s symbolic significance.

Ethiopia

The Tigray people believed in Ethiopia that hurting a wild dog would result in the animal dipping its tail into its wounds and flicking the blood back at the attacker, resulting in death. Tigrean shepherds, on the other hand, choose to defend themselves against wild dog attacks by using stones rather than bladed weapons.

Citizens of San

The mythology of the San people of Southern Africa also has a prominent role in the African wild dog. The Hare is cursed by the moon to be hunted by African wild dogs after refusing the moon’s offer to allow all living creatures to be reincarnated after death in a single story. According to another myth, the god Cain takes revenge on the other gods by sending a pack of African wild dogs disguised as men to attack them. It is unclear who emerged victorious from the conflict. African wild dogs are revered by Botswana’s San people, who believe shamans and healers can take on the appearance of wild dogs. You are smearing African wild dog bodily fluids on your foot before a hunt is considered to give you the animal’s strength and agility. The antelope does not frequently appear in San rock art, except for a frieze representing a group chasing two antelopes on Mount Erongo.

Ndebele

To understand why the African wild dog hunts in packs, Ndebele people tell a narrative about the first wild dog’s wife becoming unwell. Hare had a visit from an impala. Impala was given a medicinal calabash by Hare, who also cautioned him against turning back before reaching Wild Dog’s den. The leopard’s scent alarmed the impala, who turned and dropped the medicine. Following this encounter with Hare, a zebra sought the same treatment and advice. Zebra shattered the gourd when he realized a black mamba was in the path. A terrible sound is heard in the midst of all: Wild Dog’s wife has died. As soon as African Wild Dog came out of the house and saw Zebra standing over the shattered gourd of medicine, he and his family went after him and slew him to death. African wild dogs continue to kill zebras and impalas in retribution for their failure to bring the medicine that could have saved Wild Dog’s wife.

According to Reports in the Press

Documentary

- In Okavango, a lone painted dog (dubbed Solo by researchers) joins forces with hyenas and jackals in the film A Wild Dog’s Tale (2013). Solo offers food and care to jackal pups.

- In Season 1 of Savage Kingdom (2016), National Geographic aired The Pale Pack, a narrative about the leaders of a pack of African wild dogs in Botswana, written and produced by Brad Bestelink and narrated by Charles Dance.

- During the fourth episode of the 2018 television series Dynasties, Tait is the aged grandmother of a pack of painted wolves in Zimbabwe’s Mana Pools Park. Blacktip, the mother of a competing group with a 32-member brood, ejected her and her crew from their territory. The human, hyena, and lion populations grew over Tait’s lifetime, reducing their shared habitat. During a drought, Tait takes her family into a lion pride’s area, where they are pursued for eight months by Blacktip’s pack. This “singing” was witnessed after Tait’s death for reasons unapparent.

African Wild Dog vs Hyena

African wild dogs and hyenas are both carnivorous predators found in Africa, but they have several differences in terms of their physical characteristics, behavior, and ecological roles.

Here are the key differences between African wild dog vs hyena:

- Social Structure: African wild dogs live in highly social packs of up to 20 individuals, led by an alpha pair. They work together to hunt and care for their young, and have a strict hierarchy within the pack. In contrast, hyenas live in groups called clans, which can consist of up to 80 individuals. Within the clan, there is a strict hierarchy, with the dominant female at the top.

- Hunting Strategy: African wild dogs are known for their highly efficient pack hunting strategy, where they work together to chase down and kill their prey. They have a high success rate in hunting, and can take down large prey such as antelopes. Hyenas, on the other hand, are more opportunistic hunters and scavengers. They have powerful jaws and can break open bones to access marrow, and are known for their ability to take down large prey such as wildebeest and zebra.

- Physical Appearance: Another difference between wild African dogs vs hyenas is their physical appearance. African wild dogs have a distinctive coat pattern of black, white, and brown patches, with large, rounded ears. They have long legs and are relatively slender. In contrast, hyenas have a sloping back and a powerful build, with shaggy fur and smaller, pointed ears.

- Ecological Role: African wild dogs play an important role in controlling herbivore populations, and are considered to be a keystone species in some African ecosystems. Hyenas also play an important ecological role as scavengers, helping to clean up dead animal carcasses and prevent the spread of disease. However, they are also known to hunt and kill prey, and can have a significant impact on local wildlife populations.

Even though there are more differences between hyena vs African wild dog, both animals play important roles in their respective ecosystems and are fascinating examples of African wildlife.

African Wild Dog Facts

African Wild Dog are interesting creatures and there are a lot of fun facts about African wild dogs to learn about.

Check out these facts about African wild dogs:

- An African wild dog puppy is born deaf and blind, and relies on their sense of smell to locate their mother and littermates. They typically stay in the den for the first few weeks of their lives, and are cared for by the entire pack, not just their mother.

- Puppy African wild dog are incredibly playful and curious. They often engage in mock fights with each other, which helps them to develop important hunting and social skills. As they get older, they will start to participate in the pack’s hunts, learning from the adults how to chase down and kill prey.

- African wild dog pups are born in litters of up to 20 individuals, although the average litter size is around 10. This is one of the largest litter sizes of any carnivorous mammal, and is thought to be an adaptation to compensate for the high mortality rate of the species.

- The main reason why are African wild dogs endangered is due to the destruction and fragmentation of their natural habitats due to human activities such as agriculture, logging, and development.

- African wild dog hunting rely on their speed, endurance, and cooperation to bring down prey. They often hunt in packs of 6 to 20 individuals, and have a success rate of around 80%.

- The African wild dog size is relatively small compared to other large carnivores in Africa. They typically weigh between 20 to 30 kilograms (44 to 66 pounds) and stand about 60 to 75 centimeters (24 to 30 inches) tall at the shoulder.

- It is unusual to have a domesticated African wild dog. Many countries have laws against keeping wild animals as pets, and it is illegal to capture and keep African wild dog pets without proper permits and licenses

- There aren’t many african wild dog predators due to their cooperative hunting behavior, speed, and agility. However, lions are one of their main predators, and they will often steal prey from wild dog packs if given the opportunity.

These are just a few African wild dog fun facts, but there’s so much more to learn about them!

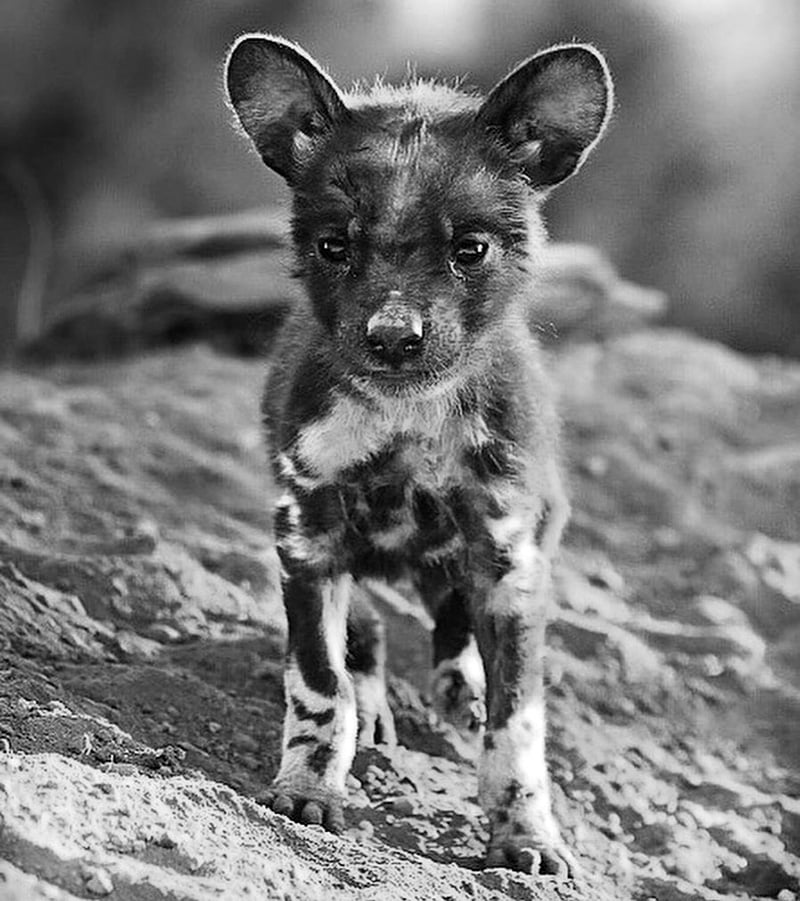

Pictures of the African Wild Dog

Check out these pictures of wild dogs in Africa!

Cute African wild dog

FAQs

Why is the African wild dog endangered?

The African wild dog is endangered due to habitat loss, human persecution, disease, and low genetic diversity. Conservation efforts are needed to protect this species and ensure its survival.

How many African wild dogs are left?

It is estimated that there are currently between 3,000 and 5,500 African wild dogs left in the wild.

Where do African wild dogs live?

African wild dogs are found in sub-Saharan Africa, primarily in savannas, grasslands, and woodland habitats.

Can African wild dogs be domesticated?

African wild dogs are wild animals and are not typically kept as pets or domesticated.

For more articles related to Wildlife in Tanzania (Animals), click here!