Barabaig Tanzania – History, Society, Cattle, Burial and More

The Barabaig are a Datooga nomadic tribe who live in the volcanic highlands around Mount Hanang in Tanzania’s Manyara Region. They speak the Datooga language‘s eponymous dialect. They have a population of around 50,000 people.

History of the Barabaig Tribe Tanzania

The Barabaig are a Nilotic community who migrated southwards to East Africa over a thousand years ago from the Nile Valley in Northern Africa. Among the Tatoga-speaking population, they are the most populous. According to linguists, the Barabaig arrived in present-day Kenya in the late 1st millennium AD and gathered around Mt. Elgon until about 250 years ago. German explorers discovered them in the late 1800s on the plain of Serengeti in German East Africa, present-day Tanzania. Archaeological findings suggest they remained around Ngorongoro Highlands up until roughly 150 years ago, when the Maasai drove them out, who still call the region “Mountains

of the Tatoga” (Osupuko loo Ltatua). The Tatoga traveled south down East Africa’s eastern branch, splitting into several groups called emojiga. Due to the emphasis that they put on sticks as weapons and percussion instruments during dances, those who inhabited the plains around Mt HMt.ang were nicknamed BaraBarabaig meaning sticks beaters (baig = sticks, bar = to beat). They inhabit Hanang Plains in Manyara Region’s Hanang District situated in north-central Tanzania, where they approximate between 35,000 to 50,000 people (even though it is not possible to be certain of the exact number because ethnicity is not recorded during the Tanzania census).

Several Barabaig were expelled forcibly from Basotu Plains during the 90s to make way for the large-scale project of wheat plantation by the governments of Tanzania and Canada.

Barabaig Society

There is no supreme chief or leader among the Barabaig (acephalous society). They are divided into clans, which consist of descendants that are traceable back to one single ancestor. Each dosht or Barabaig clan has a chief, who convenes a clan council to oversee the clan’s activities. 6 spiritual clans (known as “asdaremng’ajega”), as well as over thirty secular clans (homatk). Except for the clan of the blacksmith (Gidang’odiga), members of all clans have to marry outside their respective clans (exogamy). Due to a deemed lack of ceremonial purity, blacksmiths were required to marry from within themselves (endogamy).

A series of jural moots or councils maintain social order in the Barabaig community, each having a different authority. The public assembly, or Gitabaraku of all the Barabaig, deals with the concerns of the whole community. The Girgwageda Dosht deals with clan matters, the Girgwageda Gisjeuda deals with neighborhood issues, while the Girgwageda Gademg deals with offenses committed by men towards women. Serious crimes are handled in-camera, with a Makchamed consisting of chosen senior elders imposing sanctions.

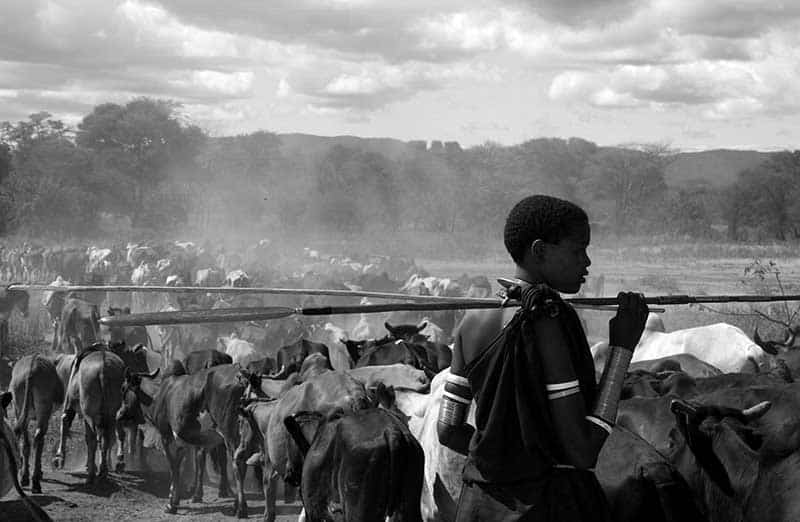

The Barabaig make a living through hunting, animal husbandry, and farming.

The Barabaig have a culture of solely using spears to hunt their adversaries (harlots), which include lions, elephants, and other creatures. Anyone who accomplishes so is seen as a hero (“ghadyirochand”) by his tribe and is gifted with women, cattle, and reputation.

Traditional animist practices and beliefs serve as the religion of all Datooga. The Datooga and Barabaig have been listed as “unreached people” by fundamentalist United States evangelicals.

Cattle

Barabaig culture is centered around cattle. They provide meat, milk and occasionally provide blood for food, skin for clothing, horns for drinking vessels, urine for cleansing, and dung for construction. Cattle are sold or bartered by the Barabaig to obtain whatever else they need. The Barabaig have not been crop growers traditionally, although they currently cultivate beans, maize, and sorghum on-farm plots. They also have gardens close to their homesteads where they grow vegetables. Almost all the products are consumed domestically. Goats and sheep are also herded, and donkeys are used for manual labor. The Barabaig also keep chickens, although they do not eat eggs. Sheep play a crucial role in rituals as a sacrifice. Goats are traded and butchered for food. Cattle, on the other hand, dictate their lives and shape their culture. Cattle act as currency, tying society together through gifts, inheritance, and loans, as well as fines, payments, and sacrifice. A Barabaig man without livestock cannot hold a social position or be respected.

Cattle are often thought to have greater social value than economic value among the Barabaig because of the central role cattle play. This is supposed to be an explanation for why they usually refuse to sell them, despite repeated attempts to bring them into the commercial meat business. Many people believe the misconception that the Barabaig hoard cattle. They raise cattle for milk rather than meat, and they make every effort to increase the cow herd in order to increase milk production. The Barabaig are willing to sell male cattle so as to obtain what they require, but selling female cattle would diminish the breeding cattle herd in addition to limiting their ability to survive. There is proof that they possess fewer cattle than previously thought.

Barabaig Burial

The Barabaig set themselves apart from other pastoralists in East Africa by burying revered elders in a special ritual called bung’ed. Bung’ed refers to the burial mound as well as the 9-month ceremony that goes with it. Before a Barabaig elder (rarely a woman) is given a bung’ed, his clan holds discussions to decide if he qualifies by having had a virtuous life, with many children and wives, owning several cattle, commanding power through oratory, displaying daring actions, and displaying smart judgment. If this is the case, the Barabaig elder is buried seated naked, facing east, with a mound built up around his body. Following that, the burial ground becomes sacred, bears the name of the deceased, and the clan preserves it in perpetuity.

Nomadism

The Barabaig are a nomadic community, moving around and beyond the Hanang Plains on a grazing rotation. During the dry season, Barbaig’s can be found mostly on the Barabaig Plains, which are located south of Mt Hanang. They migrate their cattle northwards to the Basotu Plains during the wet season when the surface water is enough for them to graze the rich grasslands known as muhajega. They travel outside their natural area to the vast river basins in the country’s southern part during extremely difficult periods. Today, the government’s alienation of most of the muhajega land for a wheat project funded by Canada has stifled migration to the Basotu Plains.

Barabaig Land loss

Julius Nyerere, the president of Tanzania, personally requested Pierre Trudeau, the Prime Minister of Canada, to assist in increasing the production of wheat locally in the 1960s to meet the rising domestic wheat demand. This led to a bilateral agreement on aid for the Canada-Tanzania Wheat Program, which was based around Basotu Plains, due to its perfect wheat-growing conditions.

To implement the program, the government of Tanzania alienated forty hectares of valuable grazing area for 7 farms between 1978 to 1981, disrupting the Barabaig grazing rotation as well as displacing many people from their homes. This territory was regarded as communal property, and like other common lands, the Barabaig found it difficult to defend. Even though some herders lived in this area all year, others just visited it at specific times of the year, but because they were not available all the time, it was assumed to be ’empty,’ justifying its grabbing.

In Tanzania, one cannot own land, but one enjoys customary rights of usage over it. The Barabaig had a customary claim to this land because they had lived there for over 150 years. The Barabaig claimed the state had violated their customary rights by taking the land away from them. They filed a lawsuit in the High Court against the agent of the government, the National Agriculture and Food Corporation (NAFCO), which operated the farms. Following an initial ruling in favor of the Barbaig in Yoke Gwako and five others versus NAFCO and Gawal Farm (1998 Civil Case No.52), the judgment was overruled on appeal due to legal technicalities (Kakoti & Tengo, R., G. 1993 The Land Case of Barbaig: Mechanics of government-organized grabbing of land in Tanzania in Dahl, J., Veber, H., Waehle, E., & Wilson, F., “Never Drink from one cup”, CDR/IWGIA, Copenhagen).

The Barabaig as well as their pastoral productivity have suffered as a result of this land loss. Aside from losing their property, they have been forced to endure the damage to sacred sites, as well as violations of their rights such as rapes, beatings, and summary fines, as well as convictions for trespassing on farms that result in incarceration. Canada has already pulled out of the scheme, and two of the plots (totalling 20,000 acres) have been given back to local Barabaigs. However, the area is still at risk of alienation.

For more articles related to Tanzania Tribes, click here!