The Swahili People – History, Religion, Language, Economy & More

Who are the Swahili People?

Swahili people (speakers of WaSwahili) belong to the Bantu ethnic group of East Africa. People from this ethnic group are mainly on the Swahili coast, including coastal Kenya, the Zanzibar archipelago, northern Mozambique, Tanzania seaboard, Northwest Madagascar, and Comoros Islands.

Of recent, Swahili people is any Muslim African person who speaks Swahili as the first language, and among the major urban centres of modern-day coastal Kenya and Tanzania, Comoros and northern Mozambique, through a Swahilization.

Swahili is from سواحل in Arabic and Sawāhil Roman, literally meaning ‘coasts‘. People of Swahili origin speak the Swahili language. The endonym for the Swahili people is Waungwana to mean the civilized ones. Modern-day Swahili is from the Kiunguja dialect in Zanzibar. Although Swahili is a Bantu language, the language includes some Arabic words, especially those used for administrative descriptions. Additionally, other words are from Hindi, German, and Portuguese.

More ancient dialects, including Kitumbatu and Kimrima, have very few Arabic words to indicate the language’s underlying Bantu character. Kiswahili was the lingua franca at the East African coast and commercial language since the 9th century. Traders from Zanzibar intensely went into the interior of Africa during the late 18th century to promote the use of Swahili as a common language all over most of East Africa. So, Kiswahili is a prevalent spoken African language, yet it is used by more people than only the Waswahili themselves

Explanation

Where Do Swahili People Live in Africa?

Swahili people come from the Bantu who lived along Africa’s southeast coast, in Mozambique, Tanzania, and Kenya. These agriculturalists were Bantu-speakers who inhabited the coast towards the beginning of the first millennium. Archaeological discoveries at Fukuchani, along Zanzibar’s northwest coast, revealed a settled fishing and agricultural community dating back to the 6th century CE up to date.

A substantial amount of daub discovered revealed shell beads, timber buildings, bead grinders, iron slag, and shell beads onsite. Evidence existed regarding limited participation in the caravan trade: a few imported pottery were discovered, making up not more than one percent of all total pottery discoveries, mainly from the Gulf dating back to the 5th and 8th centuries.

Like modern sites, including Dar es Salaam and Mkokotoni, united communities became the first center for maritime culture at the coast. The coastal cities appeared to have participated in the Indian Ocean trade by this time. Trade rapidly grew in significance and extent from the middle of the 8th to11th century.

Some Swahili people allege Shirazi origin to form the grounds for the origin of the myth regarding the Shirazi era that infiltrated the coast towards the coming of the millennium. Contemporary academics deny the originality of the claims regarding Persian origin. These refer to the comparative uniqueness of Persian speech and customs, the absence of documentary proof regarding Shia Islam among the Muslim literature along the Swahili Coast, also the rather heavy presence of Sunni Arab-related background proof.

Factual proof such as archaeology regarding ancient Persian settlements is missing. The potential origin of the stories regarding the Shirazi came from Muslim dwellers in the Lamu archipelago who migrated south during the 10th -11th centuries. These people came with a system of coins and Islam in indigenous form. The muslim migrants of African descent probably came up with the idea of Shirazi origin while moving further southwards, close to Mombasa and Malindi, on the coast of Mrima.

The long term trade relationships with the Persian Gulf endowed credibility to these stories. Since many Muslim communities are patrilineal, it’s possible to allege distant identities by paternal lines regardless of somatic and phenotypic evidence in contradiction. The alleged Shirazi tradition symbolizes the onset of Islam during those eras, a reason there has been long-lasting proof.

Existent mosques and coins portrayed the “Shirazi” as Muslim Swahili from the north but not immigrants from the Middle East. They migrated south, establishing mosques, bringing coins, mihrabs and precise carvings with inscriptions. The Shirazi should be seen as local Muslim Africans who benefited from the Middle East politics.

Some still use the foundation myth a millennium later when asserting their authority, despite its context being long forgotten. This Shirazi legend gained new significance during the 19th century, in the era of Omani control. Allegations regarding Shirazi descent were to natives away from Arab invaders as the Persians were not seen just like Arabs though they possessed good Islamic lineage.

Emphasizing that the Shirazi arrived much earlier and went into mixed marriages with locals connects this allegation to the formation of compelling local stories regarding Swahili people ancestry without separating it from the idea of a maritime-centred culture.

Two significant theories exist regarding the origins of the Shirazi subdivision of Swahili. A thesis focusing on oral tradition reveals that migrants from the Shiraz area in Iran’s southwestern region directly inhabited multiple islands and mainland ports along the seaboard of East Africa since the 10th century.

When the Persians settled in the region, earlier inhabitants were already displaced by incoming Nilotic and Bantu populations. Other people from various areas of the Persian Gulf kept on coming to the Swahili coast spanning different centuries afterwards, and these established the contemporary Shirazi. Another theory regarding the origins of the Shirazi says they migrated from Persia before first settling in the Horn of Africa.

During the 12th century, as the gold trade with the faraway Sofala entrepot along the Mozambique seaboard, the settlers were said to have migrated southwards to multiple coastal cities in Tanzania, Kenya, Indian Ocean islands, and northern Mozambique. In 1200 CE, these had set up local mercantile networks and sultanates on various islands, including Mafia, Comoros, and Kilwa on the Swahili coast and in Madagascar’s northwest.

The mother tongue of contemporary Swahili people is Swahili of the Bantu group of the Niger-Congo lineage. This language has Arabic words.

Main Religion of Most of the Swahili People

In about the 9th century, Islam was established along Africa’s southeast coast. After the settling of Bantu traders along the coast who joined the networks of Indian Ocean trade. Swahili people belong to the Sunni group of Muslims.

Vast numbers of Swahili people do the Umrah and Hajj from Tanzania, Mozambique, and Kenya. Traditional Islamic dressing, including thob and jilbab, is famous amongst Swahili. Using divination is popular among the Swahili people, including the adoption of syncretic features from underlying indigenous beliefs. These people believe in djinn, with most men wearing defensive amulets having Quran verses.

Practicing divination among the Swahili people is by use of readings from the Quran. The diviner treats various ailments using Quran verses. Occasionally, he can instruct the patient to soak a paper with Quran verses in water. When the water is infused with ink containing Allah in words, the patient has to drink or wash his body using this water to heal from any affliction. Only Islam teachers and prophets are allowed to become diviners among Swahili.

Language of the Swahili People

What People Speak Swahili and Where Do People Speak Swahili?

People speaking Swahili and whom we can consider the language as their mother tongue are the Bantu subdivision of the Niger-Congo ancestry. The closest relatives of the Swahili language include Comorian of the Comoros Islands and Mijikenda of the Mijikenda people, Kenya.

With the first people to speak it mainly on Zanzibar and parts of the coast in Tanzania and Kenya, the coastline known as the Swahili Coast, it became the language of Africa’s Great Lakes area’s urban class. Finally, it became the lingua franca in the period after colonialism.

People in Swahili Economy

The Swahili people relied mainly on the Indian Ocean trade for centuries. These people played an essential role as middlemen between the rest of the world and central, south, and southeast Africa. Ancient Roman writers who visited the coast of southeast Africa discovered trade connections as early as 100 CE.

Trade routes went as far as Tanzania, Kenya, modern-day Congo, together with goods brought to the coasts for selling to Indian, Portuguese, and Arab traders. Archaeological and historical archives say the Swahili were great maritime sailors and merchants who navigated Africa’s southwest coastline to further lands, including Persia, Arabia, India, Persia, Madagascar, and China.

Arabian beads and Chinese pottery were discovered in the ruins of Great Zimbabwe. At the peak of the Middle Ages, slaves and ivory became substantial revenue sources. Various Swahili people captured by the Portuguese and sold in Zanzibar were moved up to Brazil, then a colony of Portugal. Swahili fishers today are still depending on the ocean for their primary source of income. These sell fish to their neighbors inland to get products from the interior.

Despite many Swahili people living below the standards of the upper hierarchy in wealthy nations, they are generally taken to be comparatively robust economically because of their trading history. The Swahili are relatively well-off; The United Nations revealed that Zanzibar’s per capita GDP was 25 percent higher than other parts of Tanzania. The economic leverage promoted the continuous spread of the Swahili culture and language all over East Africa.

Architecture of the Swahili People

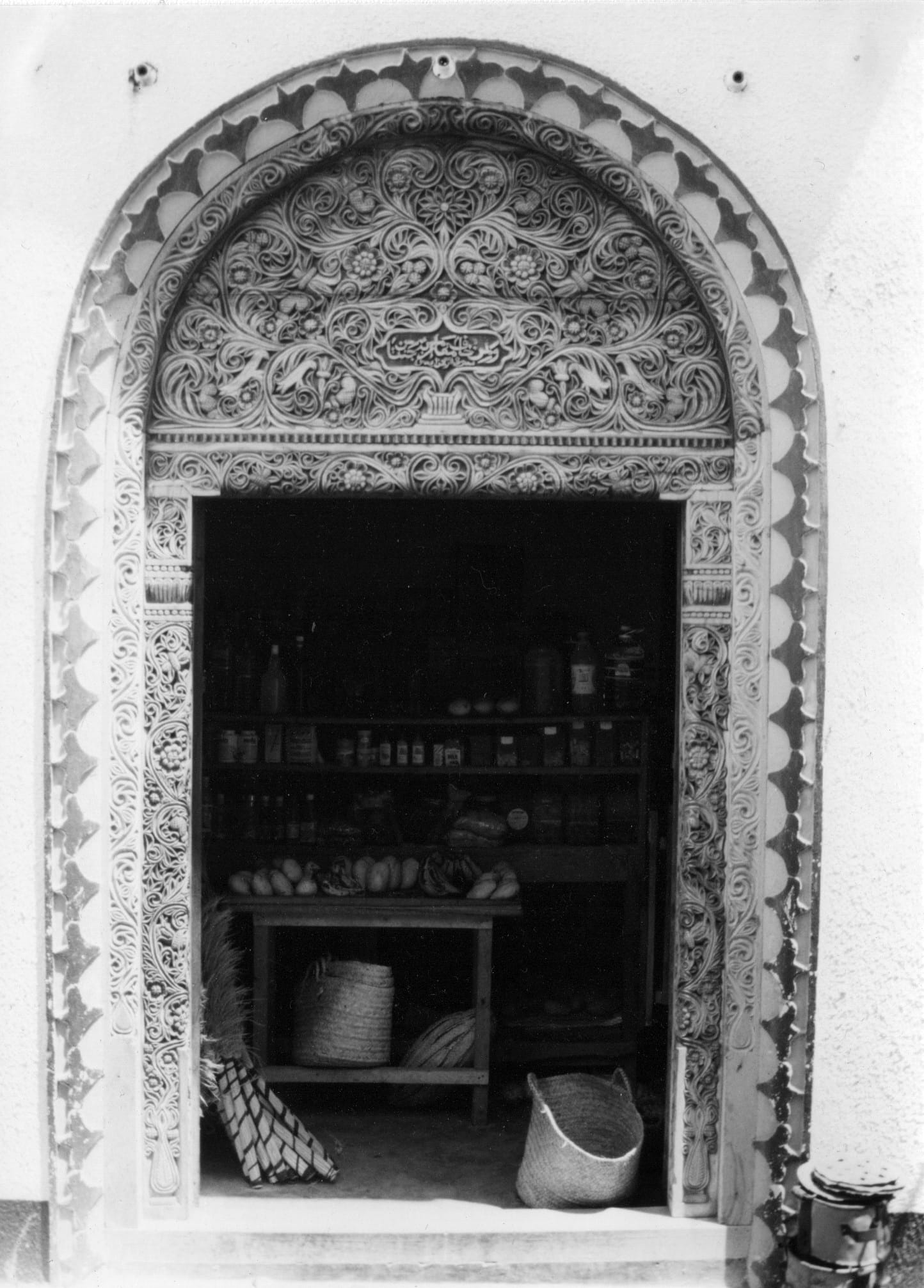

Formerly believed by most scholars as essentially Persian or Arabic origin and style, written, archaeological, cultural and linguistic evidence; however, generally recommends African sustainment and genesis. This was to be supported afterwards by a continuing Islamic and Arabic influence in trade and ideas exchange.

In 1331 after visiting Kilwa Kisiwani, Ibn Battuta, a great Berber explorer, was impressed with the substantial beauty he found there. His description of its dwellers as “Zanj” or pitch black with faces having tattoo marks revealed that Kilwa was a wonderful and substantially built town and with all wooden buildings (his account of Mombasa was similar).

Kimaryo noted the distinctive tattoos popular among the Makonde. The building included courtyards, arches, towers, isolated quarters for women, decorative elements, and mihrab. Most ruins, including the Gede ruins (Gede or Gedi lost town), are still visible around Malindi Port in southern Kenya.

Frequently Asked Questions About Swahili People

- How many people speak Swahili? – natives is about 16 million peoplle, but when combined with those that are second language the number climbs up to 200 million people.

- Famous Swahili people:

-

- Abdisalam Ibrahim

- Musa Mudde

- Jamal Mohamed

- Shabani Nonda

- Mohamed Husseini

- Yussuf Poulsen

- Charles Okere

- Saad Musa

For more articles on the Tanzania Tribes click here!