Indian Ocean – Everything You Need to Know

The Indian Ocean is the third largest ocean in the world. It covers 27,240,000 square miles (70,560,000 sq km) or 19.8 percent of the water on the Earth’s surface. Australia borders the Indian Ocean to the east, while Africa and Asia border it to the west and the north, respectively. Depending on how it is defined, the ocean is bounded by Antarctica or the Southern Ocean to the south. The ocean has some large regional or marginal seas along its core, like the Laccadive Sea, the Arabian sea, the Bay of Bengal, the Andaman Sea, and the Somali Sea.

Etymology

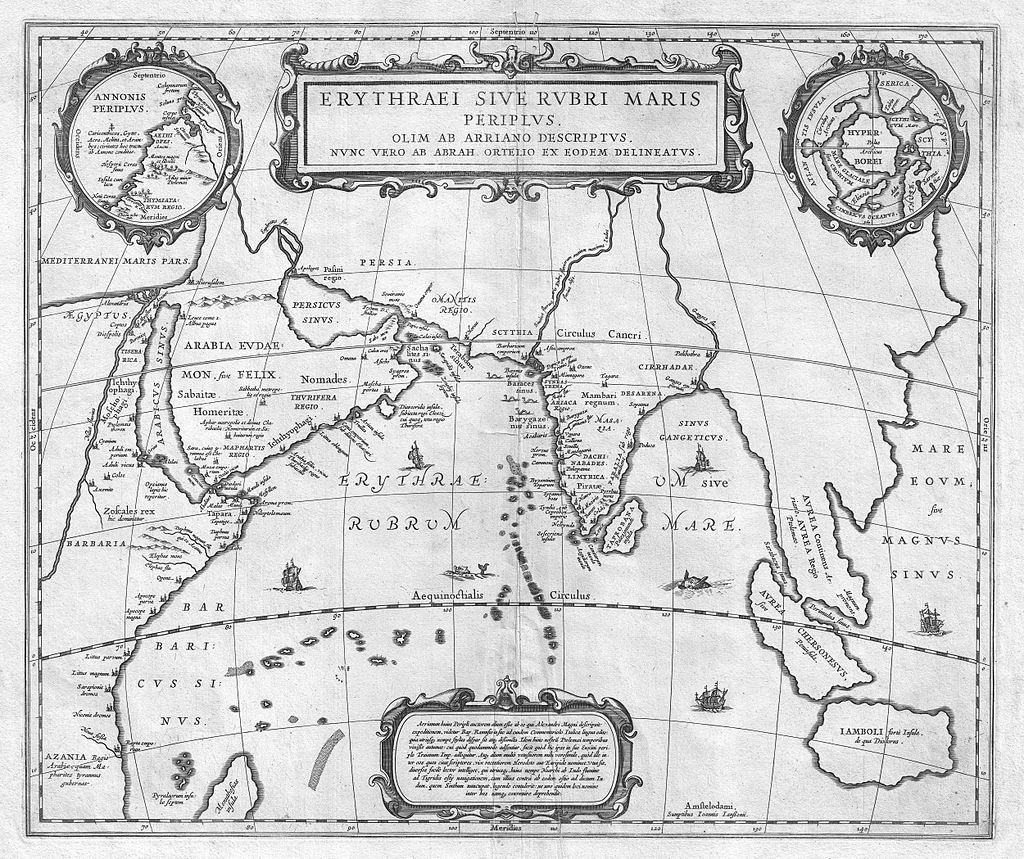

The Indian Ocean has been known by its current name since 1515, when the Latin term Oceanus Orientalis Indicus (Indian Eastern Ocean) is attested. It was named after India, which extends into it. Previously, it was referred to as the Eastern Ocean, a name still in use during the mid-18th century, as opposed to the Western Ocean (Atlantic) before the Pacific was surmised.

On the other hand, Chinese explorers that explored the ocean during the 15th century referred to it as the Western Oceans. The Indian Ocean has been known by other names like Indic Ocean and Hindi Mahasagar in different languages.

The Indian Ocean, known to the Greeks in ancient Greek geography, was referred to as the Erythraean Sea.

Geography

Indian Ocean Extent and Data

The Indian Ocean’s borders, as demarcated by the International Hydrographic Organisation (IHO) in 1953, did not include the minor seas located along the northern rim but included the Southern Ocean. However, the IHO demarcated the Southern Ocean separately in 2000. The new demarcation removed waters 600S of the Indian Ocean, although it included the minor northern seas.

Meridionally, the 200 east meridian delimits the Indian Ocean from the Atlantic oceans, flowing south from Cape Agulhas. In contrast, the meridian of 146049’E that runs south from the southernmost part of Tasmania delimits the Indian Ocean from the Pacific Ocean. The northernmost extent of the Indian Ocean (including minor seas) is roughly 300 north in the Persian Gulf.

The Indian Ocean covers 27,240,000 square miles (70,560,000 sq km2), including the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, excluding the Southern Ocean, or 19.5 percent of the world’s oceans. Its volume is 63,000,000 cu mi (264,000,000 km3), or 19.8 percent of the world’s total ocean volume. The ocean has an average depth of 12,274 ft (3,741 m) and a maximum depth of 25,938 ft (7,906 m).

The entire Indian Ocean is located in the Eastern Hemisphere. The centre of the Eastern Hemisphere, the 90th meridian east, runs through the Ninety East Ridge.

Shelves and Coasts

Unlike the Pacific and Atlantic, an archipelago and major landmasses enclose the ocean on three ends. The ocean doesn’t extend from pole to pole. It can be compared to an embayed ocean. The ocean is concentrated on the Indian peninsula. Though the Indian subcontinent has played a major part in its history, the Indian Ocean has initially served as a cosmopolitan stage, linking various regions by trade, religion, and innovations since the early history of humans.

The Indian Ocean’s active margins have an average depth (land to shelf break) of 11.81 ± 0.38 mi (19 ± 0.61 km) with a peak depth of 109 mi (175km). The ocean’s passive margins have an average depth of 29.58 ± 0.50 mi (47.6 ± 0.8 km). The average widths of the continental shelves’ slopes are 32.6-31.3 mi (52.4-50.4 km) for passive and active margins, respectively, with a peak depth of 158.6-127.6 mi (255.2-205.3 km)In correspondence to the Hinge zone, also referred to as Shelf break, the Bouguer gravity ranges between 0 and 30mGals which is unexpected for a continental region of close to 16 km thick sediments. It has been speculated that the “Hinge zone may be the relic of proto-oceanic and continental crustal boundary created when India rifted from Antarctica.”

India, Australia, and Indonesia are three countries that have the lengthiest shorelines. The three countries also have exclusive economic zones. The continental shelf constitutes 15 percent of the Indian Ocean. Over two billion people inhabit countries that border the Indian Ocean, compared to only 1.7 billion that live around the Atlantic Ocean and 2.7 billion that live around the Pacific Ocean (certain countries border multiple oceans).

Rivers

The drainage basin of the Indian Ocean covers 8,100,000 sq mi (21,100,000km2), almost identical to the Pacific Ocean’s and half that of the Atlantic basin, or thirty percent of its ocean surface (compared to the Pacific’s 15 percent). The drainage basin of the Indian Ocean is roughly divided into 800 individual basins, 50 percent that of the Pacific Ocean. Of these 800 basins, 30 percent are located in Africa, 20 percent in Australasia and 50 percent in Asia. On average, rivers of the Indian Ocean are shorter (460 mi) (740 km)) than rivers of the other oceans of the world. The largest order 5 rivers are Ganges-Brahmaputra, Zambezi, Jubba, Murray, and Indus rivers. The largest order 4 rivers are the Limpopo river, Wadi Ad-Dawasir (a river system located on the Arabian Peninsula that has dried out) and Shatt al-Arab rivers. After the formation of the Himalayas and the breakup of East Gondwana, the Ganges-Brahmaputra rivers flow into the Bengal delta.

Minor Seas

The Indian Ocean’s minor seas, bays, straits, and gulfs include:

The Mozambique Channel, along the east coast of Africa, which breaks off Madagascar from mainland Africa, while the Sea of Zanj is located north of Madagascar.

The strait of Bab-el-Mandeb connects the Gulf of Aden to the Red Sea on the northern coast of the Arabian sea. In the Gulf of Aden, the Gulf of Tadjoura is found in Djibouti, while the Horn of Africa is separated from the Socotra island by the Guardafui Channel. The Red Sea’s northern end stops in the Gulf of Suez and the Gulf of Aqaba. Through the Suez Canal, which can be accessed through the Red Sea, the Mediterranean Sea is artificially connected to the Indian Ocean without a ship lock. The Strait of Hormuz and the Gulf of Oman connect the Arabian Sea to the Persian Gulf. In the Persian Gulf, the Arabic Peninsula is separated from Qatar by the Gulf of Bahrain.

Along the Indian west coast, the Gulf of Khambat and the Gulf of Kutch are located in Gujarati in the northern end, while the Maldives is separated from the southern end of India by the Laccadive Sea. The Bay of Bengal is located off the east coast of India. India is separated from Sri Lanka by the Palk Strait and the Gulf of Mannar, while Adam’s Bridge divides the two. The Andaman Sea lies between the Andaman Islands and the Bay of Bengal.

The so-called Indonesian Seaway in Indonesia is made up of Sunda, Torres, and Malacca Straits. The Great Australian Bight makes up a huge part of the southern Australian coast, while the Gulf of Carpentaria is found on its north coast.

- Gulf of Suez

- Gulf of Khambat

- Gulf of Kutch

- Flores Sea – 240,000 km2

- Arabian Sea – 3.862 million km2

- Mozambique Channel – 700,000 km2

- Molucca Sea – 200,000 km2

- Laccadive Sea – 786,000 km2

- Gulf of Aqaba – 239 km2

- Great Australian Bight – 45,926 km2

- Andaman Sea – 797,700 km2

- Oman Sea – 181,000 km2

- Persian Gulf – 251,000 km2

- Gulf of Aden – 410,000 km2

- Red Sea – 438,000 km2

- Timor Sea – 610,000 km2

- Bay of Bengal – 2.172 million km2

Climate

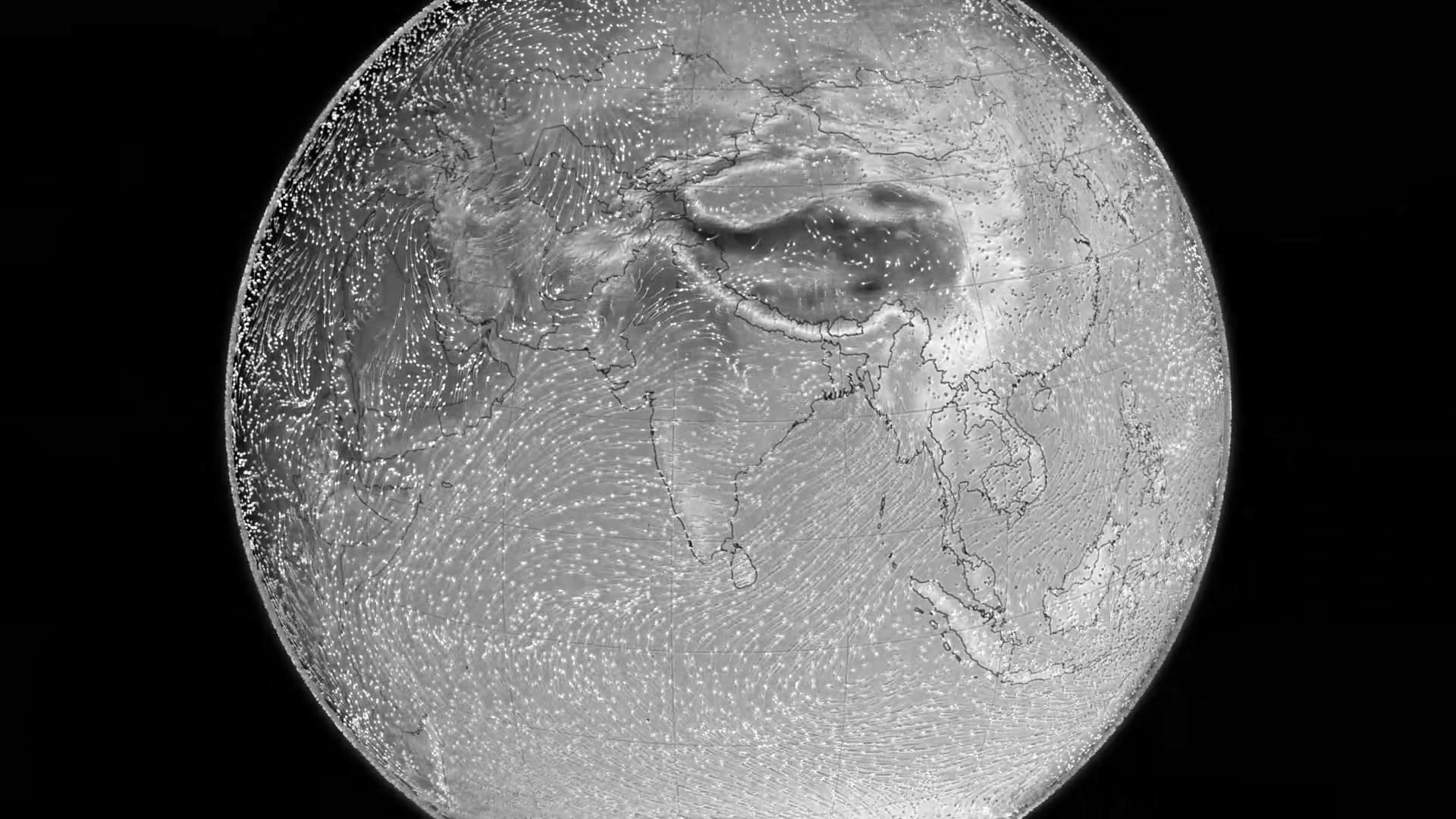

Many unique attributes differentiate the Indian Ocean. It makes up the centre of the large-scale Tropical Warm Pool, which affects the global and regional climate when interacting with the atmosphere. Heat export and the ventilation of the Indian Ocean thermocline are prevented by Asia. The continent also drives the strongest monsoon on Earth, the Indian Ocean Monsoon. The monsoon is known to cause large-scale periodic changes in ocean currents, including the turn around of the Indian Monsoon Current and the Somali Current. There are no uninterrupted equatorial easterlies due to the Indian Ocean Walker circulation. Upwelling occurs in the Arabian Peninsula, the Northern Hemisphere, north of the Southern Hemisphere trade winds, and close to the Horn of Africa. The Indonesian Throughflow is a special Equatorial connection to the Pacific.

The monsoon affects the climate north of the Equator. Powerful north-east winds blow from October till April; west and south winds prevail from May till October. In the Arabian Sea, rain is brought to the Indian subcontinent by the fierce monsoon. The are currents are largely gentler. However, summer storms close to Mauritius can be harsh. Sometimes cyclones hit the Arabian sea coast and the Bay of Bengal when the monsoon wind changes. Almost 80 percent of India’s total yearly rainfall falls during the summer. The region relies so much on this rainfall that various civilisations collapsed when the monsoon failed in the past. The large variability in the Indian Summer Monsoon has also happened pre-historically, with a very weak phase 17,000 to 15,000 BP; a weak, dry phase 26,000 to 23,500 BC; and a strong wet phase 33,500 to 32,500 BP that corresponded to a succession of sensational global events: Younger Dryas, Heinrich, and Bølling-Allerød.

Of all the oceans in the world, the Indian Ocean is the most temperate. Long-term temperature reports show rapid and continuous warming in the ocean, at about 34.20F (1.20C) (compared to 33.30F (0.70C) recorded for the warm pool region) between 1901 and 2012. According to research, greenhouse warming caused by humans, as well as alterations in the magnitude and frequency of the ocean’s Dipole (El Niño), trigger the strong warming in the Indian Ocean.

South of the Equator (20-5°S), the Indian Ocean gains heat between June and October during the austral winter, while it loses heat between November and March during the austral summer.

The Indian Ocean Experiment conducted in 1999 showed that biomass and fossil fuel burning in Southeast and South Asia led to air contamination (also referred to as the Asian brown cloud) that reached as far as the Intertropical Convergence Zone at 600S. The Asian brown cloud has implications locally and globally.

Oceanography

Forty percent of the Indian Ocean’s sediment is found in the Ganges and Indus fans. The basins next to the continental slopes are largely made up of terrigenous sediments. Non-stratified sediment mostly made up of siliceous oozes dominate the ocean south of the polar front (approximately 500 south latitude). The area also has high biologic productivity. Close to the three prominent mid-ocean ridges, the ocean floor is relatively young and devoid of sediments; the Southwest Indian Ridge is the only exception because it has an ultra-slow dispersal rate.

The monsoon mainly controls the ocean’s currents. Two large ocean gyres, one south of the Equator flowing anti-clockwise (including the Agulhas Return Current and Agulhas Current) and another in the northern hemisphere moving clockwise, constitute the main flow pattern. However, during the winter monsoon between November and February, circulation is shifted north of 300S, and the air currents are weaker during the winter and the period of transition between the monsoons.

The largest abyssal fans in the world – the Indus Fan and Bengal Fan – are found in the Indian Ocean. The ocean also has the largest areas of rift valleys and slope terraces.

The inflow of deep water into the ocean is 11 Sverdrup. Most of the inflow comes from the CDW (Circumpolar Deep Water). The CDW flows into the Indian Ocean via the Madagascar and Crozet basins and crosses the Southwest Indian Ridge (SWIR) at 300S. The CDW turns to a deep western boundary current in the Mascarene Basin before the North Indian deepwater (a recirculated section of itself) meets it. This mixed water partially flows north into the Somali Basin, while most of it flows clockwise into the Mascarene Basin, where Rossby waves produce an oscillating flow.

The Subtropical Anticyclonic Gyre dominates water circulation in the Indian Ocean. The 900E Ridge and the Southeast Indian Ridge block the gyre’s eastern extension. The SWIR and Madagascar separate three cells south of Madagascar and off South Africa. The North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) enters the Indian Ocean south of Africa at a depth of 6,600-9,800 ft (2,000-3,000 m) and flows northward along Africa’s eastern continental slope. The Antarctic Bottom Water, which is a deeper water mass than NADW, flows across deep channels (13,000 ft (<4,000 m)) from Enderby Basin to Agulhas Basin in the SIWR. From there, it flows into the Prince Edward Fracture Zone and the Mozambique Channel.

The lowest surface temperature north of 200 south latitude is 720F (220C), surpassing 820F (280C) to the east. Temperatures drop sharply southward of 400 south latitude.

More than 50% (710 cu mi or 2,950km3) of the Indian Ocean’s runoff water is contributed by the Bay of Bengal. Predominantly in summer, the runoff water flows into the Arabian Sea and also south across the Equator. At the Equator, the water mixes with the Indonesian Throughflow’s fresher seawater. The mixed freshwater then joins the South Equatorial Current in the southern tropical Indian Ocean. The Arabian Sea has the highest sea surface salinity because evaporation is greater than precipitation there. Sea salinity reduces to less than 34 PSU in the Southeast Arabian Sea – the lowest in the Bay of Bengal due to precipitation and river runoff. The lower salinity (34 PSU) along the Sumatran west coast is caused by the Indonesian Throughflow and precipitation. From June to September, monsoonal variation causes the eastward movement of saltier water to the Bay of Bengal from the Arabian Sea. The East India Coastal Current moves westerly to the Arabian Sea from January to April.

In 2010, an Indian Ocean garbage patch that covers at least 1.9 million square miles (1.5 million square kilometres) was discovered. This vortex of plastic waste rides the southern Indian Ocean Gyre and rotates the ocean from Australia to Africa through the Mozambique Channel and back to Australia in six years. Only debris indefinitely stuck in the gyre’s centre are left behind. According to a study conducted in 2012, the size of the garbage patch in the Indian Ocean will reduce after many decades and completely vanish over centuries. However, over many millennia, the worldwide system of garbage patches will gather in the North Pacific.

The Indian Ocean has two amphidromes of opposite rotation, likely caused by the propagation of the Rossby wave.

Like the Pacific, Icebergs flow as far north as 550 south latitude, which is unlike the Atlantic Ocean, where icebergs drift up to 450S. From 2004 to 2012, 24 gigatonnes of icebergs were lost in the Indian Ocean.

Anthropogenic warming of the global ocean since the 1960s coupled with freshwater contributions from shrinking land ice has led to a worldwide rise in sea level. The Indian Ocean also experiences an increase in sea level except in the southern tropical Indian Ocean, where sea levels decrease. This pattern is most likely a result of increasing levels of greenhouse gases.

Marine Life

Of all the tropical oceans, the western Indian Ocean is home to one of the largest accumulations of phytoplankton blooms during summer as a result of strong monsoon winds. The monsoonal wind causes a strong coastal open-ocean upwelling, which brings nutrients to the upper zones where sufficient illumination is available for photosynthesis and the production of phytoplankton. The phytoplankton blooms support the marine ecosystem (constituting the base of the marine food web)and ultimately the bigger fish species. The Indian Ocean is responsible for the second-biggest share of the most valuable tuna catch. The fish from the ocean are of great and growing significance to the bordering countries for export and domestic consumption. Fishing fleets from Taiwan, Russia, South Korea and Japan also explore the Indian ocean, majorly for tuna and shrimp.

Research shows that rising ocean temperatures are beginning to affect the marine ecosystem. Research on the phytoplankton changes in the Indian Ocean shows a decline of up to 20 percent in the Indian Ocean’s plankton in the past 60 years. There has also been a 50 to 90 percent decline in tuna catch rates in the last 50 years, mainly because of increased industrial fisheries, with the ocean warming further adding stress to the fish species.

Vulnerable and endangered marine animals and turtles:

| Name | Trend | Distribution |

| Endangered | ||

| Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculs) | Increasing | Global |

| Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) | Decreasing | Southwest Australia |

| Sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis) | Increasing | Global |

| Irrawaddy dolphin

(Orcaella brevirostris) |

Decreasing | Southeast Asia |

| Green sea turtle

(Chelonia mydas) |

Decreasing | Global |

| Indian Ocean humpback dolphin

(Sousa plumbea) |

Decreasing | Western Indian Ocean |

| Vulnerable | ||

| Fin whale

(Balaenoptera physalus) |

Increasing | Global |

| Sperm whale

(Physeter macrocephalus) |

Unknown | Global |

| Dugong

(Dugong dugon) |

Decreasing | Equatorial Indian Ocean and Pacific |

| Indo-Pacific finless porpoise

(Neophocaena phocaenoides) |

Decreasing | Southeast Asia, Northern Indian Ocean |

| Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin

(Sousa chinensis) |

Decreasing | Southeast Asia |

| Australian snubfin dolphin

(Orcaella heinsohni) |

Decreasing | New Guinea, Northern Australia |

| Leatherback

(Dermochelys coriacea) |

Decreasing | Global |

| Loggerhead sea turtle

(Caretta caretta) |

Decreasing | Global |

| Australian humpback dolphin

(Sousa sahulensis) |

Decreasing | New Guinea, Northern Australia |

| Pacific ridley sea turtle

(Lepidochelys olivacea) |

Decreasing | Global |

Eighty percent of the Indian Ocean is an open ocean and comprises nine big marine ecosystems: the Somali Coastal Current, Bay of Bengal, Agulhas Current, Arabian Sea, Red Sea, West Central Australian Shelf, Gulf of Thailand, Southwest Australian Shelf, and Northwest Australian Shelf. Coral reefs cover approximately 77,000 sq mi (200,000 km2). The Indian Ocean’s coast includes beaches and intertidal areas that cover 1,200 sq mi (3,000 km2) and 246 bigger estuaries. Upwelling zones are tiny but important. The hypersaline salterns in India cover between 1,900 to 3,900 sq mi (5,000 to 10,000 km2), and species adapted for this environment, like Dunaliella salina and Artemia salina, are vital to birdlife. Seagrass beds, mangrove forests, and coral reefs are the Indian Ocean’s most productive ecosystems – 20 tonnes per square kilometer of fish is produced in the coastal areas. However, these areas are being urbanised with populations often surpassing several thousand people per square kilometer, and fishing methods become more effective and oftentimes destructive beyond levels that can be sustained. At the same time, the rise in the temperature of the sea surface spreads coral bleaching.

Mangroves cover 31,268 sq mi (80,984 km2) in the Indian Ocean region, or almost 50 percent of the global mangrove habitat, of which 16,400 sq mi (42,500 km2) is located in Indonesia, or half of the mangroves in the Indian Ocean. Mangroves emanated from the Indian Ocean and have adapted to many of its habitats. However, it is also where it suffers most from loss of habitat.

In 2016, six new species of animals -a “giant peltospirid” snail, a polychaete worm, a whelk-like snail, a “Hoff” crab, a scale worm and a limpet- were identified at hydrothermal vents in the Southwest Indian Ridge.

In the 1930s, the West Indian Ocean coelacanth was discovered in the Indian Ocean off South Africa. Another species, the Indonesian coelacanth, was discovered in the late 1990s off Sulawesi island in Indonesia. Most extant coelacanths are found in Comoros Island. Although the two species belong to an order of the lobe-finned fishes known from the Early Devonian (410 million years ago) and went into extinction 66 mya, they are morphologically different from their Devonian ancestors. Coelacanths, over millions of years, evolved to live in different habitats – lungs adapted for brackish, shallow waters evolved into gills adapted for deep marine waters.

Biodiversity

Nine (25 percent) of Earth’s biodiversity hotspots are found on the margins of the Indian Ocean.

- The islands of the western Indian Ocean (Réunion, Comoros, Seychelles, Socotra, and Mauritius)and Madagascar contain 13,000 plant species (11,600 are endemic); 381 reptiles (of which 367 are endemic); 164 freshwater fishes (of which 97 are endemic); 250 amphibians (of which 249 are endemic); 200 mammals (of which 192 are endemic) and 313 birds (of which 183 are endemic).

The cause of this diversity is contested. The break up of Gondwana can clarify vicariance older than 100 million years ago. However, the diversity on the smaller and younger islands must have needed a Cenozoic scattering from the Indian Ocean rims to the islands. A “reverse colonisation,” from islands to continents, seemingly happened more recently. For instance, the chameleons first diversified in Madagascar before colonising Africa. Many species on the islands of the Indian Ocean are textbook examples of evolutionary processes; the day geckos, lemurs, and dung beetles are all examples of adaptive radiation. Several bones (250 bones per square metre) of vertebrates that recently went into extinction have been discovered in the Mare aux Songes swamp in Mauritius, which included bones of the Cylindraspis giant tortoise and the Dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus). An analysis of the bones suggests that the aridification process started in the southwest Indian Ocean around 4,000 years ago.

- Coastal forests of eastern Africa contain 4,000 plant species (of which 1,750 are endemic); 636 birds (12 are endemic); 250 reptiles (54 are endemic); 219 freshwater fishes (32 are endemic); 236 mammals (7 are endemic) and 95 amphibians (10 are endemic).

This biodiversity hotspot (including the namesake ecoregion and “Endemic Bird Area”) is a mixture of small forested zones, often with a special collection of species within each, located within 120 mi (200 km) from the coast and covers a total area of approximately 2,400 sq mi (6,200 km2). It also includes coastal islands, like Mafia, Pemba and Zanzibar.

- Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany (MPA) contains 8,100 plant species (of which 1,900 are endemic; 541 birds; 205 reptiles (36 are endemic); 73 freshwater fishes (20 are endemic); 197 mammals (3 are endemic) and 73 amphibians (11 are endemic).

Mammalian megafauna that was once common in the MPA was driven to near extinction in the early years of the 20th century. Since then, a few species have been recovered successfully – the population of white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum) rose from less than 20 in 1859 to over 17,000 as of 2013. Other species still depend on management programmes and fenced areas, including African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis minor), lion (Panthera leo), cheetah (Acynonix jubatus), and elephant (Loxodonta Africana).

- The Horn of Africa contains 5,000 plant species (of which 2,750 are endemic); 704 birds (25 are endemic); 284 reptiles (93 are endemic); 100 freshwater fishes (10 are endemic); 189 mammals (18 are endemic) and 30 amphibians (6 are endemic).

The area is one of the two hotspots entirely dry. It includes the East African Rift Valley, the Ethiopian Highlands, the Socotra islands and some smaller islands in the Red Sea, as well as areas on the southern Arabic Peninsula. Threatened and endemic animals include the hamadryas baboon (Papio hamadryas) and Somali wild ass (Equus africanus somaliensis); Speke’s gazelle (Gazella spekei), and dibatag (Ammodorcas clarkei). There are also many reptiles there. In Somalia, the centre of the 580,000 sq mi (1,500,000 km2) hotspot, Acacia-Commiphora deciduous bushland dominates the landscape. It also includes the Yeheb nut (Cordeauxia edulus) as well as species that were recently discovered, like the Somali cyclamen (Cyclamen somalense), the solitary cyclamen found outside the Meditteranean. Warsangli linnet (Carduelis johannis) is an endemic bird that is only found in northern Somalia. Overgrazing, aided by an unstable political regime, has resulted in one of the most degraded hotspots, with only about 5 percent of the original habitat remaining.

- Indo-Burma contains 13,500 plant species (of which 7,000 are endemic); 401 mammals (of which 100 are endemic); 518 reptiles (of which 204 are endemic), 1277 birds (of which 73 are endemic); 328 amphibians (of which 193 are endemic); and 1,262 freshwater fishes (of which 553 are endemic).

Indo-Burma includes a series of mountain ranges, a wide range of habitats, as well as five of the largest river systems in Asia. The region has a complex and long geological history. Long periods of glaciations and rising sea levels have disconnected ecosystems and therefore promoted a high level of speciation and endemism. The region is also home to two centres of endemism: the northern highlands on the Vietnam-China border and the Annamite Mountains. Many distinct regions, the Sino-Himalayan, Malesian, Indochinese, and Indian regions, uniquely meet in Indo-Burma. The hotspot also contains between 15,000 to 25,000 species of vascular plants, many of which are endemic.

- Southwest Australia contains 5,571 plant species (of which 2,948 are endemic); 55 mammals (of which 13 are endemic); 32 amphibians (of which 22 are endemic); 20 freshwater fishes (of which 10 are endemic); 177 reptiles (of which 27 are endemic); and 285 birds (of which 10 are endemic).

Isolated by the dry Nullarbor Plain and stretching from Shark Bay to Israelite Bay, the southwestern corner of Australia is a floristic zone with a stable climate from where one of the largest floral diversity in the world and an 80 percent endemism has evolved. It is an explosion of colors between June and September, and the Wildflower Festival held in September in Perth attracts more than 500,000 visitors.

- Wallacea contains 10,000 plant species (of which 1,500 are endemic); 244 mammals (of which 144 are endemic); 49 amphibians (of which 33 are endemic); 650 birds (of which 265 are endemic); 222 reptiles (of which 99 are endemic); and 250 freshwater fishes (of which 50 are endemic).

- Sundaland contains 25,000 plant species (of which 15,000 are endemic); 950 freshwater fishes (of which 350 are endemic); 397 mammals (of which 219 are endemic); 258 amphibians (of which 210 are endemic); 771 birds (of which 146 are endemic); 449 reptiles (of which 244 are endemic).

Sundaland includes 17,000 islands, of which Sumatra and Borneo are the largest. Endangered mammals include the proboscis monkey, the Sumatran and Bornean Orangutans, the Sumatran and Javan rhinoceros.

- The Western Ghats-Sri Lanka contains 5,916 plant species (of which 3,094 are endemic); 191 freshwater fishes (of which 139 are endemic); 204 amphibians (of which 156 are endemic); 143 mammals (of which 27 are endemic); 265 reptiles (of which 176 are endemic); and 457 birds (of which 35 are endemic).

The area encompasses the west coast of India and Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka was linked to the Indian subcontinent by a landbridge until about 10,000 years ago. Thus, this region shares a common community of species.

Geology

Being the youngest of the major oceans, the Indian Ocean has active spreading ridges that form part of the global system of mid-ocean ridges. In the Indian Ocean, these spreading ridges meet with the Central Indian Ridge at the Rodrigues Triple Point, including the Carlsberg Ridge that separates the African plate from the Indian Plate; the Southeast Indian Ridge that separates the Australian Plate from the Antarctic Plate; and the Southwest Indian Ridge that separates the African Plate from the Antarctic Plate. The Owen Fracture Zone intercepts the Central Indian Ridge. However, since the late 1990s, it has become clear that the traditional definition of the Indo-Australian Plate can’t be right. It comprises three plates – the Capricorn Plate, the Australian Plate and the Indian Plate – divided by diffuse boundary zones. Since 20 ma, the East African Rift System has been dividing the African Plate into the Somali and the Nubian plates.

There are just two trenches in the Indian Ocean: the 560 mi (900 km)-long Makran Trench located south of Pakistan and Iran and the 3,700 mi (6,000 km)-long Java Trench between Java and the Sunda Trench.

Hotspots produce a series of seamount chains and ridges that pass over the Indian Ocean. The Kerguelen hotspot (100–35 million years ago) links the Kerguelen Plateau and the Kerguelen Islands to the Ninety East Ridge and the Rajmahal Traps in north-eastern India; the Réunion hotspot (active 70–40 million years ago) links the Mascarene Plateau and Réunion to the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge and the Deccan Traps in north-western India, and the Marion hotspot (100–70 million years ago) possibly links the Prince Edward Islands to the Eighty-Five East Ridge. The still-active spreading ridges discussed above have broken these hotspot tracks.

Compared to the Pacific and the Atlantic, there are fewer seamounts in the Indian Ocean. These are usually deeper than 9,800 ft (3,000 m) and situated west of 800E and north of 550S. Most of them originated at spreading ridges. However, some are now situated in basins far from these ridges. The Indian Ocean’s ridges form ranges of seamounts that are sometimes very lengthy, including the Central Indian Ridge, Madagascar Ridge, Carlsberg Ridge, East Indiaman Ridge, Chagos-Laccadive Ridge, 90°E Ridge, Broken Ridge, 85°E Ridge, Southeast Indian Ridge, and the Southwest Indian Ridge. The Mascarene Plateau and the Agulhas Plateau are the two major shallow areas.

The opening of the Indian Ocean started around 156 Ma when Africa broke off from East Gondwana. The Indian subcontinent started to break off from Australia-Antarctica 135 to 125 Ma. As the Tethys Ocean north of India started to close 118 to 84 Ma, the Indian Ocean opened behind it.

Indian Ocean History

Since ancient times, the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean have linked people, whereas the pacific and the Atlantic have been mare incognitum or barriers. However, the Indian Ocean’s written history has been Eurocentric and largely reliant on the availability of written documents from the colonial period. Oftentimes, this history is divided into an ancient period that precedes an Islamic period; the periods that follow are often subdivided into British, Dutch, and Portuguese periods.

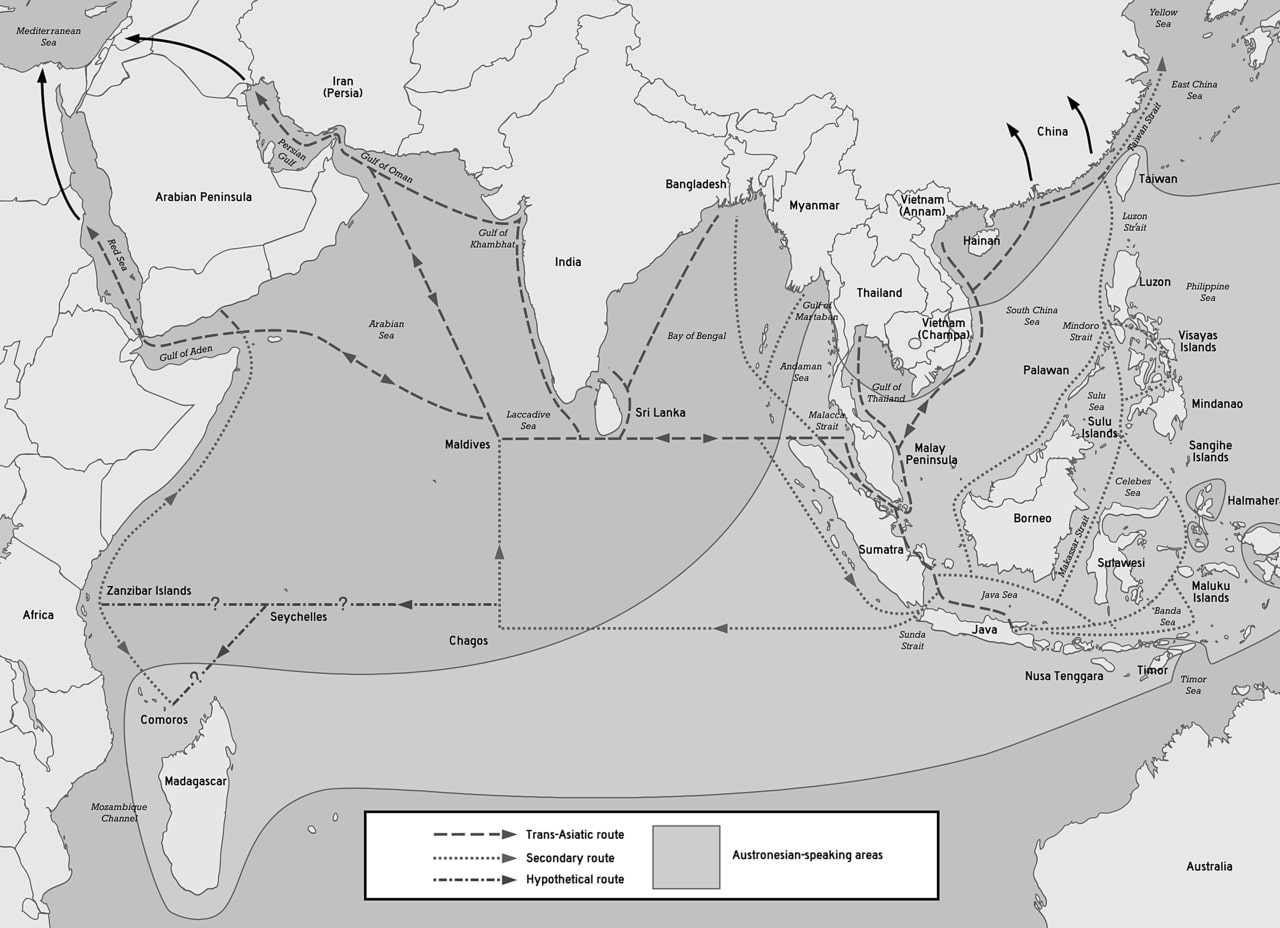

An idea of an “Indian Ocean World” (IOW), akin to the “Atlantic World,” exists. However, it came up more recently and is not firmly established. Nevertheless, the IOW is sometimes called the “first global economy” and was based on the monsoon that connected India, China, Mesopotamia, and Asia. It prospered independently from the European global trade in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean and stayed largely independent until the colonial dominance of the Europeans in the 19th century.

The Indian Ocean’s diverse history is a special mix of ethnic groups, cultures, shipping routes, and natural resources. Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, it grew in importance and has witnessed periods of political instability since the end of the cold war, most recently with the rise of China and India as regional powers.

First Settlements

Pleistocene fossils of Homo erectus and other pre-Homo sapiens hominid fossils, akin to Homo heidelbergensis in Europe, have been discovered in India. According to the Toba catastrophe theory, a supereruption approximately 74,000 years ago at Lake Toba in Sumatra covered India with volcanic ashes. It obliterated one or more lineages of such ancient humans in Southeast Asia and India.

According to the Out of Africa theory, Homo sapiens spread from Africa to mainland Eurasia. However, the more recent Coastal Hypothesis or Southern Dispersal advocates that modern humans dispersed along the coasts of southern Asia and the Arabic Peninsula. Mitochondrial DNA research that shows a swift dispersal event 11,000 years ago during the Late Pleistocene supports the theory. However, this coastal dispersal started in East Africa 75,000 years ago and happened periodically from one estuary to the next along the northern border of the Indian Ocean at a rate of 0.43-2.49 mi (0.7-0.4 km) per year. Eventually, it resulted in the migration of modern humans from Sunda over Wallacea to Sahul (Southeast Asia to Australia). People have been resettled by waves of migration, since then and clearly, the coast of the Indian Ocean had been occupied long before the emergence of the first civilisations. 5,000 to 6,000 years ago, six different cultural centres had developed around the Indian Ocean: the Middle East, East Africa, South East Asia, Australia, the Malay World, and the Indian Subcontinent; each interlinked to its neighbours.

Food globalization started on the littoral of the Indian Ocean c. 4.000 years ago. Five African crops – pearl millet, sorghum, hyacinth bean, cowpea, and finger millet – somehow made their way to Gujarat, India, during the Late Harrapan (2000 to 1700 BCE). Gujarati merchants became the first explorers of the Indian Ocean while trading African goods like tortoise shells, slaves, and ivory. Together with zebu cattle and chicken, broomcorn millet found its way to Africa from Central Asia, although the exact timing is contested. Around 200 BCE, sesame and black pepper, both native to Asia, appeared in Egypt, although only in small quantities. Around that same time, the house mouse and the black mouse emigrated to Egypt from Asia. Banana got to Africa around 3,000 years ago.

Between 7,400 and 2,900 years ago, not less than 11 prehistoric tsunamis have struck the coast of Indonesia. Analyses conducted by scientists on sand beds in caves located in the Aceh region concluded that the intervals between the tsunamis have varied from series of minor tsunamis over 100 years to dormant periods of over 2,000 years preceding megathrusts in the Sunda Trench. Though the risk of future tsunamis is high, a long dormant period will likely follow a major megathrust like the one in 2004.

A team of scientists have contended that a pair of large-scale impact events have taken place in the Indian Ocean: the Kanmare and Tabban craters in the Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Australia in 536 CE and the Burckle Crater in the southern Indian Ocean in 2800 BCE. The team argued that chevron dunes and micro-ejecta found in the Australian gulf and in southern Madagascar are proofs of these impacts. Geological evidence suggests that these impacts caused tsunamis that reached 673 ft (205 m) above sea level and 28 mi (45 km) inland. These impact events must have broken up human settlements and perhaps also contributed to major changes in the climate.

Antiquity

Maritime trade characterizes the ocean’s history. Commercial and cultural exchange probably dates back at least 7,000 years. Human culture spread early on the coasts of the Indian Ocean and was linked to the cultures of the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean. However, prior to c. 2000 BCE, cultures on the shores of the ocean were only loosely connected. For instance, bronze was developed in Mesopotamia around 3000 BCE but was not common in Egypt prior to 1800 BCE. During this era, independent, short-distance overseas communications along the ocean’s littoral margins expanded into an all-embracing network. The debut of this network did not result in an advanced or centralised civilisation; instead, it resulted in regional and local exchange in the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea, and the Persian Gulf. Sherds of Ubaid (2500 to 500 BCE) pottery have been discovered in the western Gulf at Dilmun, present-day Bahrain, indicating traces of exchange between Mesopotamia and this trading centre. The Sumerians traded bitumen (used for reed boats), pottery, and grain for stone, copper, timber, dates, pearls, tins, and onions.

Vessels headed to the coast moved goods between the Indus Valley Civilisation (2600 to 1900 BCE)in the Indian subcontinent (present-day Northwest India and Pakistan) and Egypt and the Persian Gulf.

The Red Sea was one of the major trade routes in Antiquity. Phoenicians and Egyptians explored the Red Sea during the last two millennia BCE. Greek explorer Syclax of Caryanda journeyed to India in the 6th century BCE, where he worked for Persian king Darius. His now-lost account put the Indian Ocean on the maps of Greek explorers. The Greeks started exploring the Indian Ocean after Alexander the Great’s conquests. In 323 BCE, Alexander the Great commanded a circumnavigation of the Arabian Peninsula. In the two centuries that followed, the reports of the explorers of Ptolemaic Egypt resulted in the best maps of the area until the Portuguese era hundreds of years later. The Ptolemies’ main interest in the area was military and not commercial. They explored Africa mainly to hunt for war elephants.

The Rub’al Khali desert removes the Indian Ocean and the southern areas of the Arabic Peninsula from the Arabic world. This promoted the development of maritime trade in the area connecting the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea to India and East Africa. However, sailors had been using the monsoon (derived from the Arabic term for season – mawsim) long before Hippalus “discovered” it in the 1st century. Indian wood has been discovered in Sumerian cities, there is proof of Akkad coastal trade in the area, and contacts between the Red Sea and India dates back to 2300 BC. The archipelagos of the central Indian Ocean, the Maldive and Laccadive Islands, were likely populated from the Indian mainland during the 2nd century. They were found in written history in the account of trader Sulaiman al-Tajir in the 9th century. However, the islands’ treacherous reefs were most probably cursed by Aden sailors long before the islands were even populated.

Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, an Alexandrian guide of the world beyond the sea – including India and Africa – from the 1st century CE, provides insights into trades in the region and shows that Greek and Roman sailors already knew the monsoon winds. The contemporary settlement of Madagascar by Austronesian seafarers indicates that the littoral margins of the Indian Ocean were regularly traversed and well-populated, at least by this time. However, monsoon must have been commonly known in the Indian Ocean for centuries.

Due to its relatively calmer waters, the Indian Ocean opened the places bordering it to trade earlier than the Pacific or Atlantic oceans. The strong monsoons also meant ships easily head west early in the season, wait for a few months and head back towards the east, thus allowing ancient Indonesians to cross the Indian Ocean to live in Madagascar around 1 CE.

In the 1st or 2nd century BCE, Eudoxus of Cyzicus became the first Greek to cross the Indian Ocean. The likely fictitious seafarer Hippalus is said to have learned the direct path from Arabia to India around the time. During the 2nd and 1st centuries AD, thorough trade relations developed between the Tamil kingdoms of the Cholas, Pandyas, and Cheras in Southern India and Roman Egypt. Like the Indonesian people mentioned above, the western seafarers used the monsoon to cross the ocean. This route and the commodities that were exchanged along various commercial harbours on the shores of India and the Horn of Africa around 1 CE were described by the unknown writer of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Opone and Mosylon on the Red Sea littoral were among these trading settlements.

Age of Discovery

Unlike the Pacific Ocean, where the Polynesian civilisation reached most of the islands and atolls located far away and populated them, almost all the archipelagos, atolls, and islands of the Indian Ocean were not occupied until the colonial period. Although there were many ancient civilizations in the coastal areas of Asia and some parts of Africa, the Maldives islands were the only island group in the Central Indian Ocean Area where an ancient civilization thrived. On their yearly trade trip, Maldivians travelled to Sri Lanka instead of mainland India, which is nearer due to the fact that their ships depended on the Indian Monsoon Current.

Arabic merchants and missionaries began spreading Islam along the western coasts of the Indian Ocean from the 8th century or earlier. A Swahili stone masjid dating to the 8th to 15th centuries has been discovered in Shanga, Kenya. The exchange of goods across the Indian Ocean slowly introduced Arabic script and rice as a staple food in East Africa. Moslem traders traded an estimated 1,000 African slaves yearly between 800 and 1,700, which grew to around 4,000 during the 18th century, and 3,700 between 1800 to 1870. Slave trade also took place in the eastern Indian Ocean prior to the arrival of the Dutch around 1600. However, the size of this trade is not known.

Between 1405 to 1433, Admiral Zheng He was said to have led large fleets belonging to the Ming Dynasty on several treasure adventures through the Indian Ocean, eventually reaching the coastal states of East Africa.

During his first journey in 1497, the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama encircled the Cape of Good Hope, becoming the first European to sail to India. The Swahili tribe he met along the east coast of Africa inhabited a series of cities and had created trade routes to China and India. Vasco da Gama abducted many of their pilots in coastal attacks and onboard ships. However, some of the pilots were gifts given by native Swahili rulers, including the seafarer from Gujarat, a gift from a Malindi ruler in Kenya, who helped da Gama to get to India. In explorations after 1500, da Gama attacked and colonised cities along the coast of Africa. European slave trade in the Indian Ocean started when Portugal created Estado da Índia in the early 16th century. From that time till the 1830s, around 200 slaves were taken from Mozambique yearly, and similar numbers have been estimated for slaves brought in from Asia to the Philippines during the Iberian Union (1580 to 1640).

Following the defeat of Egypt under Sultan Selim I, the Ottoman Empire commenced its expansion into the Indian Ocean in 1517. Despite the fact that the Ottomans shared the same faith as the trading communities of the Indian Ocean, they were yet to explore the ocean. Moslem geographers had produced maps that included the Indian Ocean hundreds of years before the Ottoman conquests. Moslem scholars, such as Ibn Battuta in the 14th century, had toured most parts of the known world at the same time as Vasco da Gama. Arab explorer Ahmad ibn Majid had composed a guide to navigating the Indian Ocean; nevertheless, the Ottomans started their parallel period of discovery that rivalled the European expansion.

The creation of the Dutch East India Company in the early 17th century led to a rapid increase in the volume of the slave trade in the area; there were close to half a million slaves in many Dutch colonies during the 18th and 17th centuries in the Indian Ocean. For instance, up to 4,000 African slaves were used to construct the Colombo fortress in Dutch Ceylon. Bali, as well as neighbouring islands, supplied regional networks with around 100,000 to 150,000 slaves from 1620 to 1830. Chinese and Indian slave traders supplied Dutch Indonesia with up to 25,000 slaves during the 18th and 17th centuries.

The East India Company was created during the same period, and in 1622, one of its ships conveyed slaves from the Coromandel Coast to Dutch East Indies. The East India Company mainly traded in African slaves, but some Asian slaves were also bought from Indian, Chinese, and Indonesian slave traders. The French created colonies on the islands of Mauritius and Réunion in 1721. By 1735, around 7,200 slaves occupied the Mascarene Islands, a figure that had risen to 133,000 in 1807. However, the British seized the islands in 1810, and because the Brits had banned the slave trade in 1807, an underground slave trade system was created to bring slaves to French planters on the islands. In all, 336,000 to 388,000 slaves were taken to the Mascarene Islands from 1670 to 1848.

Overall, 567,900 to 733,200 were exported by the European traders within the Indian Ocean between 1500 and 1850 and almost the same number were exported to the Americas from the Indian Ocean during the same period. Nevertheless, the slave trade in the Indian Ocean was very limited compared to about 12,000,000 slaves that were exported across the Atlantic.

Modern Era

Scientifically, the Indian Ocean remained insufficiently researched prior to the International Indian Ocean Expedition conducted in the early 1960s. However, the Challenger expedition (1872 to 1876) reported only from south of the polar front. The Valdivia expedition (1898 to 1899) created deep-seated samples in the Indian Ocean. In the 1930s, the John Murray Expedition chiefly examined shallow-water habitats. The Swedish Deep-Sea Expedition of 1947 to 1948 also examined the Indian Ocean during its worldwide tour, and the Danish Galathea examined deepwater fauna from Sri Lanka to South Africa during its second expedition from 1950 to 1952. Also, the Soviet research ship Vityaz researched the Indian Ocean.

The Suez Canal was opened in 1869 after the Industrial Revolution changed global shipping dramatically – the importance of the sailing ship declined, as did the importance of European trade in favour of trade in Australia and East Asia. Many non-native species were introduced into the Mediterranean after the construction of the canal. For instance, the red mullet (Mullus barbatus) has been replaced by the goldband goatfish (Upenus moluccensis); since the 1980s, large swarms of scyphozoan jellyfish (Rhopilema nomadica) have affected tourism and fishing along the Levantine coast and clogged desalination and power plants. In 2014, plans to construct a new and much larger Suez Canal were announced. The new canal will be like the 19th-century canal and will likely improve the economy in the area. However, it will cause ecological damage in a much wider area.

Throughout the colonial period, islands like Mauritius were crucial shipping nodes for the British, Dutch and French. Mauritius was an inhabited island, and it soon became populated by slaves brought from Africa and indenture labour sourced from India. The end of the Second World War marked the end of the colonial period. The Brits left Mauritius in 1974, and Mauritius became India’s close ally due to the fact that 70 percent of the population had Indian ancestry. During the Cold War in the 1980s, the South African government tried to destabilise many island countries in the Indian Ocean, including Madagascar, Comoros, and Seychelles. India came to the rescue to prevent a coup d’etat in Mauritius. India had the backing of the United States of America, who were afraid that the Soviet Union could have access to Port Louis and threaten its base on Diego Garcia. Iranrud is an unrealised plan by the Soviet Union and Iran to construct a canal between the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea.

Testimonies from the colonial period are tales of Indian indentured labourers, white settlers, and African slaves. However, while a clear racial line exists between slaves and free men in the Atlantic World, the delineation is less prominent in the Indian Ocean – there were Indian settlers and slaves as well as black indentured labourers. A string of prison camps also existed across the Indian Ocean, from Cellular Jail in the Andamans to Robben Island in South Africa, where exiles, forced labourers, POWs, people of different religions, and merchants were forcefully united. Therefore, a creolisation trend emerged on the islands of the Indian Ocean.

On December 26, 2004, a wave of tsunamis that resulted from the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake hit 14 countries around the Indian Ocean. The waves blazed across the ocean at over 310 mph (500 km/h), reached up to 66 ft (20 m) in height, and led to an estimated 236000 deaths.

The ocean became a hub of pirate activities in the late 2000s. By 2013, attacks off the coast of the Horn region had dropped considerably as a result of active private security as well as international navy patrols, particularly by the Indian Navy.

Malaysian Airline Flight 370, a Boeing 777 aircraft conveying 239 people, disappeared on March 8, 2014, and is purported to have crashed into the southern Indian Ocean about 1,600 mi (2,500 km) from the coast of southwest Western Australia. Although a far-reaching search was conducted, the remains of the aircraft were not found.

Experts have referred to the Sentinelese people that live in North Sentinel Island near South Andaman Island in the By of Bengal as the most isolated people in the world.

The Chagos Archipelago’s sovereignty is disputed between Mauritius and the UK. In February 2019, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague released an advisory opinion declaring that the United Kingdom must transfer the archipelago to Mauritius.

Trade on the Indian Ocean

Globally, the sea lanes in the Indian Ocean are among the most strategically important. Over 80% of the world’s seaborne oil trade moves through the Indian Ocean and its important chokepoints – 40% pass through the Strait of Hormuz, 35% go through the Strait of Malacca, and 8% pass through the Bab el-Mandab Strait.

The Indian Ocean also provides important sea routes that connect East Asia, Africa and the Middle East with the Americas and Europe. The ocean carries a particularly heavy traffic of petroleum products and petroleum from the oil fields of Indonesia and the Persian Gulf. Huge reserves of hydrocarbons are being tapped in the offshore parts of Iran, Saudi Arabia, Western Australia and India. The Indian Ocean is responsible for an estimated 40 percent of global offshore oil production. Bordering countries like Pakistan, Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India and South Africa exploit offshore placer deposits and beach sand rich in heavy minerals.

The maritime area of the Silk Road runs through the Indian Ocean, on which a large chunk of the global container trade takes place. The Silk Road runs with its connections from the Chinese shore and its huge container ports to the south through Hanoi to Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore through the Strait of Malacca through the Sri Lankan Colombo opposite the southern tip of India through the capital of the Maldives (Male) to the East African Mombasa, from there to Djibouti, then via the Red Sea over the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean, there through Athens, Istanbul, and Haifa to the Upper Adriatic to the northern Italian junction of Trieste with its international free port and its rail connections to Eastern and Central Europe.

On the one hand, the Silk Road has become globally important again because of free world trade, the end of the cold war and European integration and on the other hand, through Chinese initiatives. Chinese firms have invested in many Indian Ocean ports, including Sonadia, Hambantota, Gwadar, and Colombo. This has led to a debate about the strategic consequences of these investments. Also, there are Chinese investments and other related efforts to boost trade in Eastern Africa and in European ports like Trieste and Piraeus.