Shirazi People – History, Religion, Language, Culture and More

The Shirazi or Mbwera make up an ethnic group living along the Swahili coast and the islands of the Indian Ocean nearby. These people are mainly concentrated on the Pemba, Comoros, and Zanzibar.

Various Shirazi legends spread on the coast of East Africa (EA), many regarding a known or unknown prince from Persia marrying a local princess. Contemporary academicians don’t buy this school of thought regarding primary Persian origin. These points put the relative absence of Persian speech and customs, missing documented proof of Shia Islam among the Muslim writings along the Swahili Coast, but rather a historic presence of Sunni-Arab evidence. Documented evidence, such as archaeological evidence for ancient Persian settlement, is entirely missing.

The Shirazi were instrumental in spreading Islam along the Swahili Coast, participated in establishing the Swahili sultanates in the south including Angoche and Mozambique, immense wealth, and role in the growth of the Swahili language. The EA coastal area and surrounding islands were their trading base.

History

Resemblances of a Myth: Arabs and Persians

Two main myths exist about the Shirazi origins. The first one is based on oral tradition which claim that Shiraz immigrants from Iran’s southwestern region directly inhabited multiple ports on the mainland and African islands in the eastern seaboard at the start of the 10th century, in the place between Somalia northwards, Sofala southwards, and Mogadishu.

Irving Kaplan revealed that before the 7th century, the areas at the coast inhabited by “Bushmanoid” Africans were usually visited by immigrants from Persia. During the Persian settlement, these earlier inhabitants had been displaced by oncoming Nilotic and Bantu populations. Other people from various areas of the Persian Gulf kept on migrating to the Swahili coast over various centuries afterward, and these developed the contemporary Shirazi.

Nevertheless, EA and other historians don’t accept this claim. Derek A. Wilson and Gideon S. Were revealed that Bantu communities existed on the coast of EA by 500 AD, including some settlements forming well-managed kingdoms having ruling classes with well-organized native religions.

Another theory regarding the origins of Shirazi says they originated from Persia, but initially settled on the Somali shoreline near Mogadishu. During the 12th century, while the trade in gold with the far away Sofala entrepot along Mozambique coast developed, the immigrants seemingly moved southwards to different towns on the coast of Tanzania, Kenya, the islands in the Indian Ocean, and northern Mozambique. During 1200 AD, these had developed local mercantile networks and sultanates on the islands of Mafia, Kilwa, and Comoros in northwestern Madagascar and on the Swahili coast.

Contemporary academicians refuse the validity of the main claim regarding Persian origin. These consider the relative uniqueness of Persian speech and customs, the absence of documentary proof of Shia Islam throughout Muslim writings along the Swahili Coast, rather a historic plethora of evidence about Sunni-Arab connections. The documented evidence, such as archaeological evidence regarding ancient settlement of Persians is entirely lacking.

Various versions exist regarding Shirazi settlement on the Swahili Coast. J. de V. Allen revealed in a seminal 1983 article called “The ‘Shirazi’ Problem in East African Coastal History,” from his work, he had hope to eliminate for good the notion that EA Shirazi’s had definitely originated from immigrants who came from the Gulf of Persia. It is evident that regardless of the existence of these immigrants with some playing a critical role in ancient times, the Shirazi marvel itself is entirely African.

The Shirazi were linked to the islands of the Lamu Archipelago in the Indian Ocean towards Kenya in the north, which according to oral traditions it was where 7 Shirazi brothers from southern Iran settled. Descendants of the Lamu archipelago moved southwards from the 10th to the 11th century. There is a dispute over this and the opposite view reveals that the legend of the Shirazi gained new significance by the 19th century, in the era of Omani domination.

Allegations of Persian Shirazi origin were used to keep natives away from the Arab immigrants. The accentuation that the Shirazi arrived in the olden days and engaged in mixed marriages with natives is reformist politics that tries to blend the theory of Shirazi origins with Swahili heritage as noticed from this angle.

Africans Who Speak Bantu Language

Contemporary scholars now mainly agree that the Shirazi and the Swahili people descended from Bantu-speaking cultivators who moved to the coast of EA during the first millennium in the Current Era (C.E). These took on maritime instruments and systems, such as sailing and fishing, and created a healthy trade network in the region by the 8th century C.E.

An increase in trade in the Indian Ocean following the 9th century C.E. introduced a surge in Muslim merchants and Islamic influence, including the start of the 12th century, various elites converted. The elites made up complex, usually fictitious, genealogies connecting them to the main Islamic areas. As traders from Persia were dominating during the early centuries in the second millennium, various Swahili patricians took on Persian traditional motifs and alleged a distant similar ancestry.

The Kilwa Chronicle, an archaic document with Portuguese and Arabic versions, shows that the ancient Shirazi also inhabited Hanzuan (also known as Anjouan, Comoros Islands), Mandakha, the Green Island (also known as Pemba), Yanbu, and Shaugu. Helena Jerman an anthropologist revealed that the Shirazi identity (Washirazi) was born after the coming of Islam during the 17th century.

There was a gradual abandonment of traditional Bantu cultural names through the substitutions with Arabic names (for example Batawiyna from Wapate), new social structures and origin stories became folklores, and there was the adoption of societal structures from Arab and Persian settlers from the Asian societies nearby.

Shirazi rulers entrenched themselves on Kenya’s Mrima coast and Kilwa’s sultan of Shirazi origin conquered the governor of Omani in 1771. Marice, a French visitor to the Sultanate approximated about one-tenth of the people were Swahili-speaking Shirazi and Arabs, a third free Africans with the rest African slaves.

Sultanates of Shirazi and non-Shirazi origin along the coast were commercial centers for slaves, ivory, timber, ambergris, and gold from the interior of Africa, and ceramics, silver and textiles, and from the Indian Ocean. The slaves were originating from the interior of Africa, including around Malawi, Mozambique, the DRC.

Islamic History

Geographers of Arab origin since the 12th and later centuries historically split Africa’s eastern coast into various regions according to each region’s dwellers. Al-Idrisi’s 12th-century geography completed in 1154 CE revealed that there existed four coastline zones:

- Barbar was also known as Bilad al Barbar meaning the land of the Berbers located in the Horn of Africa, inhabited by Somalis and stretching to the south into the Shebelle river;

- Zanj was also known as Ard al-Zanj meaning the country of the blacks, situated immediately below that up to near Tanga or Pemba island’s south side;

- Sofala was also known as Ard Sufala, stretching from Pemba to an unknown end of the line, but most likely near River Limpopo;

- Waq-Waq, a shadowy piece of land in the south thereof.

However, ancient geographers didn’t talk about Sofala. The texts that were written after the 12th century also refer to Madagascar island as dal-Qumr, and included it as Waq-Waq land.

Islam arrived in Somalia’s northern coast earlier from the Arabian peninsula, immediately after the hijra. The oldest mosque in the city, Zeila’s two-mihrab Masjid al-Qiblatayn is traced back to the 7th century. Towards the end of the 9th century, Muslims had already inhabited this northern coastline according to Al-Yaqubi’s writing. He went on to mention the existence of the Adal kingdom with its capital in the city. Further on, Ibn al-Mujawir revealed in his writing that the multiple battles in the Arabian peninsula made Yemen’s Banu Majid people settle in Mogadishu’s central area.

According to Ibn Said and Yaqut, the city was another essential Islamic center that traded actively with the Africans speaking Swahili in the region south of the city. Texts from the 13th century also talk about people and mosques having names like al-Sirafi and al-Shirazi including the Sirafi at Merca clan, suggesting earlier Persian presence in the region.

For the Barbar region in the south, Al-Masudi talks about trade on the sea from Oman and Port Siraf around Shiraz towards Africa’s Zanj coast, Waq-Waq, and Sofala. Ibn Battuta later visited the sultanate of Kilwa during the 14th century, under the rule of Sultan Hasan bin Sulayman of the Yemeni dynasty by that time. Battuta referred to most inhabitants as “Zanj ” with a “jet-black” color, the majority having tattoos on the face.

The meaning for Zanj was not for distinguishing Africans from non-Africans, but Muslims from non-Muslims. Muslims belonged to the ulama while non-Muslims were known as “Zanj.” By that time in Kilwa, Islam remained mostly limited to the noble elite. Battuta further described its leader as usually making booty and slave attacks on the infidel Africans according to his description of the Zanj nation.

From the loot, one 5th was for the Prophet’s family, with the distribution of everything following guidelines in the Koran. Regardless of these attacks on Africa’s interior populations, there existed a symbiotic relationship between the people at the coast and the Africans.

More records exist in Kitab al-Zanuj or the Book of the Zanj, a possible collection of legendary oral traditions with recollections of settler merchants along the Swahili coast. A document towards the end of the 19th-century claimed Arabs and Persians were ordered by the governors in the Persian Gulf area to capture and occupy EA’s commercial coast. It further talks about Halawani and Madagan Arab traders with unclear identities and roots establishing the Shirazi dynasty.

- F. Morton revealed that a critical evaluation of the Book of the Zanj portrays that many documents have deliberate mistruths made by Fathili bin Omari, the author. His intention was to nullify native Bantu groups’ establishment of oral traditions. Writings in the Kitab regarding the origins of the Arabian founders of Malindi including other communities along the Swahili coast are also disputed by documented 19th-century town and clan traditions, which rather emphasize that ancient Shirazi settlers had Persian ancestral background.

Many contemporary scholars agree to the presence of insignificant or no proof of substantial Asian movement to EA during the medieval era. Swahili elites, most of whom had various trade links with Persia, India, and Arabia treated themselves as exemplary Muslim nobility. This required real or fictitious genealogies that connected them back to ancient Muslims in Persia or Arabia, something common in various regions of the Islamic World.

Spending time at the cost for periods of up to 6 months was common for Persian, Indian, and Arab, Persian merchants to let the monsoon winds shift. These would usually marry the daughters of local Swahili traders, spreading their genealogy using Islam’s system of patrilineal descent. The archaeological records firmly refute any possibility of mass movement or colonization but proves extensive trade connections with Persia.

Trade connections with the Persian Gulf were especially prevalent from the 10th century to the 14th century, which encouraged the growth of local folktales regarding Shirazi or Persian origin. To Abdulaziz Lodhi, the Arabs and Iranians referred to the Swahili coast as Zangibar or Zangistan, to means “the Black Coast”, including the Muslim settlers from South Asia (present day India and Pakistan) to Arabian lands in the south including Yemen and Oman identifying themselves as Shirazi.

Communities of Muslim Shirazi along the Swahili coast preserved a close connection with those on islands like Comoros, through mixed marriage and trading networks. To Tor Sellström, the population of Comorian includes a big number of African and Arab heritage, especially on Anjouan and Grande Comore and these were under Shirazi sultanates.

Connection between the Shirazi and colonial Europeans began with the arrival of Vasco da Gama in Kilwa sultanate in 1498 (a Portuguese explorer). Some years afterward, the Shirazi and Portuguese entered into conflicts over trading tracks and rights, especially about gold; the conflict destroyed Mombasa and Kilwa ports which were towns for Shirazi rulers.

Portuguese military might and initial direct trading with India, pursued by more European powers, inspired a hasty downfall of the Shirazi cities which flourished and relied mainly on the trade. In connection with European competition, Bantu groups that were not speaking Swahili started raiding Shirazi towns during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Accordingly, the Shirazi sultanates were fighting war on land and from sea, leading to rapid loss of trading facilities and power. Arabs from Omani re-organised their army in the 17th century, and they crushed the Portuguese at Mombasa in 1698,. The Portuguese accepted to give up this part of Africa, and new migration of Arabs from Yemen and Oman into the settlements of the Shirazi people ensued.

Modern Demography

Some islands and towns have a bigger population of Shirazi people. For instance, by 1948, around 56 percent of the people in Zanzibar disclosed Shirazi lineage of Persian origins. During local elections, voting for the Shirazi favoured any politically expedient party, including shirazi Zanzibar Nationalist Party with minorty support or Afro Shirazi Party on Tanzania mainland.

Genetic analysis according to Msadie et al. (2010) portrays that the prevalent paternal lineages of the modern population in Comoros including Shirazi people, are clades popular across sub-Saharan Africa E2-M90 (14 percent)) and (E1b1a1-M2 (41 percent). The samples also have some northern Y chromosomes, portraying the potential for paternal South Iran ancestry (E1b1b-M123, E1b1b-V22, G2a, I, F*(xF2, GHIJK), J1, L1, J2, R1*, Q1a3, R1a1, R1a*, and R2 (29.7 percent)), and Southeastern Asia (O1 (6 percent)).

The people of Comoros also mainly mitochondrial haplogroups connected to sub-Saharan EA people of East and South EA (L1, L0, L3′4 and L2 (xMN) (84.7 percent)), while the other maternal clades linked to Southeastern Asia (F3b, B4a1a1-PM, and M7c1c (10.6 percent) and M( E, xD, M1, M7, M2) (4 percent)) but without Middle Eastern ancestries.

To Msadie et al., since there exist no similar Middle East maternal haplogroups among the people of Comoros, striking evidence exists for male-biased gene flux to Comoros from the Middle East , which is wholly compatible with male-dominated commerce and religious persuasion as the forces that drove gene flow from the Middle East to the Comoros.

Religion

Many of the Muslims who speak Swahili in the customary Swahili cultural centers belong to the Sunni Islam sect.

Language

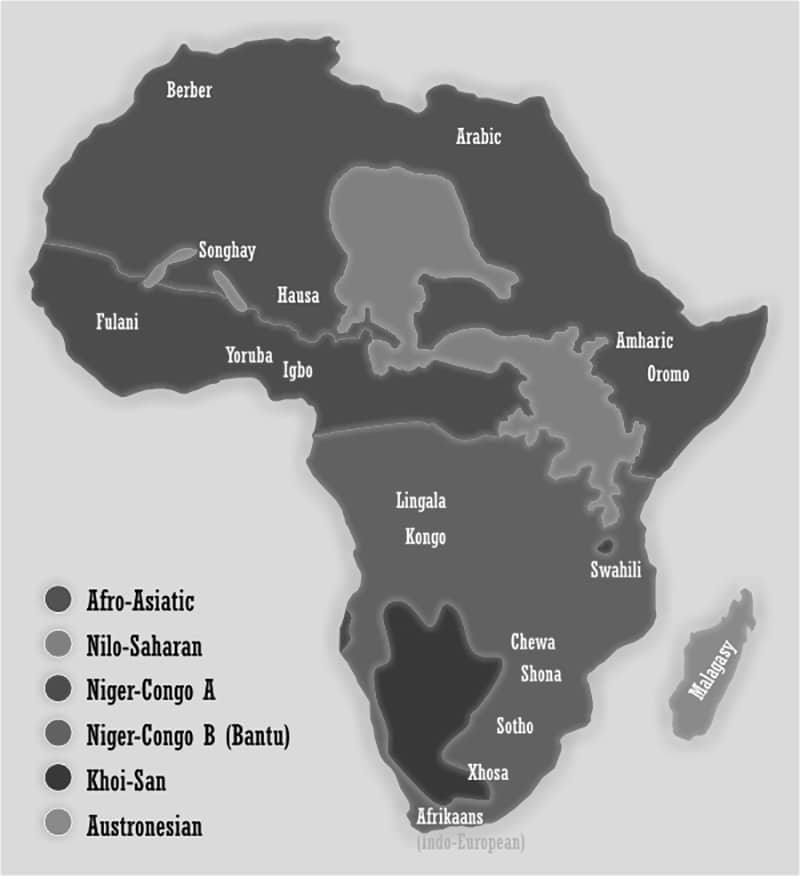

Swahili is the native language of the Shirazi Tanzania just like other Swahili people. The language is for the Bantu branch originating from the Niger-Congo lineage. Nevertheless, Swahili language dialects are described better as a syncretic language blending with Comoro, Sabaki Bantu, Iranian, Pokomo, India, and Arabic phrases and structure portraying the syncretic blending of people from various backgrounds that formed the Shirazi tribe.

Comorian is split into two lingo factions, the first group in the west includes Shimwali and Shingazidja, and the other in the east includes Shindzwani and Shimaore. People who speak Shingazidja are about 312,000 on Ngazidja. People who speak Shindzwani are about 275,000 in Ndzwani. Speakers of Shimaore are about 136,500 on Mayotte. About 28,700 people speak Shimwali on Mwali.

People who speak Comorian languages rely on Arabic script for their writing structure.

Society and Culture

People of Shirazi Tanzania origin have been a predominantly mercantile community, relying on trade. At first from the 10th to 12th centuries, Mozambique’s gold-producing areas attracted them to Africa’s coast. Later the trade in African slaves, spices, silk, ivory,and produce from coconut, clove, and other plantations worked on using slave labor grew into a mainstream trading activity. Raids inland led to the capture of African slaves.

Memories of Islamic travelers in the 1th and 15th centuries talk about their presence in Swahili towns like that of Ibn Battuta, a 14th century explorer. The Shirazi supplied a lot of slaves to European plantations and various Sultanates during the colonial era. August Nimtz revealed that after banning of international slave trade, there was economic crippling of the Shirazi community.

The coming of Islam with the Arabs and Persians affected the identity of the Shirazi and social structures in various ways. To Helena Jerman, the phrase “Sawahil” in the Shirazi people meant a class of people in society who are free but without land who embraced Islam, then a recent social group along the Swahili coast. To the Muslims, it was the most despised social class of free people, slightly above the slaves.

Together with the Wa-shirazi class, other classes included the Wa-manga, Wa-arabu, Wa-shemali, Wa-shihiri, and Wa-ungwana (a pure Arab nobility). People of the Shirazi social class came with particular class privileges and taboos. For instance, the upper class Waungwana (also known as Swahili-Arabs) were the only ones to construct beautiful stone houses, while Waungwana men engaged in polygynous hypergamy, where they could produce children with women of low status and slaves. Waungwana women maintained sexual and ritual purity through being confined to particular sections in the house known as Ndani.

Lazare Ki-Zerbo and Michel Ben Arrous revealed that the Shirazi society was damaged by the status implications of class and race. Although Arabs from Arabia and Persia became traders and slave owners, they took their slaves to be inferior and not fit for Islam. Slave girls became concubines for producing children for them.

Male children were taken to be Muslims while the female children joined slavery and non-Muslim lineage. Still, in the society after colonialism, the remaining distinctions and dynamics of a racial class system still exist among some Shirazi. To Jonas Ewald, a sociologist and other academicians, the social differentiation among the Shirazi is not limited to races but goes beyond area of origin and economic status.

The nature of Shirazi culture is Islamic, associating mainly to its Arabic and Persian origins. Other influences were also from the Bantu including the Swahili language.

Ali Sultan Issa, G. Thomas Burgess, and Seif Sharif Hamad noted that various Africans professed Shirazi origin to hide their slave ancestry, access World War II rations supplied by the colonial masters depending on ethnicity or to stamp their landowners status. Shirazi take themselves to be of Persian origin primarily, including others regularly taking themselves not to be Arabs or new labor migrants out of Africa mainland.

For more articles on the Tanzania Tribes click here!