Palace of Husuni Kubwa Kilwa – History, Layout, Decorations, Architecture and More

Overview of Husuni Kubwa Palace

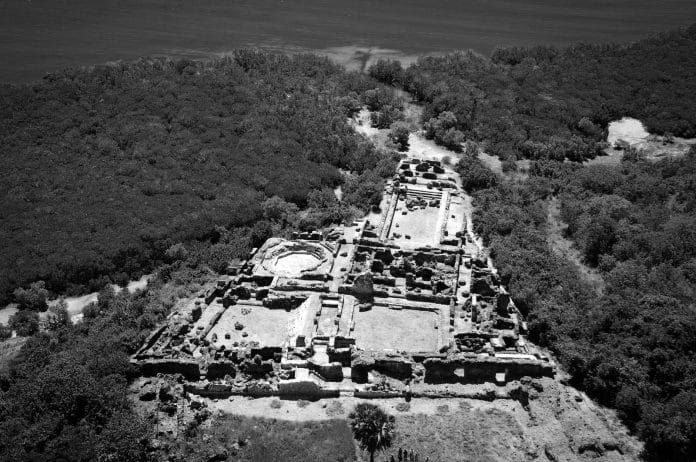

Husuni Kubwa, or “Great Palace,” was an emporium and Sultan’s palace built outside of town at the beginning of the 14th century. Other distinguishing features are platforms and causeways built from almost meter-high coral and reef blocks at the harbour’s entrance. These serve as breakwaters and allow mangroves to flourish, which helps to identify the few ways that breakwater may be seen from afar. The bedrock was utilized as a base for some segments of the causeway, but it was primarily used as a foundation. The causeways were constructed using coral stone, with lime and sand used to seal the cobbles collectively. Many of the stones stayed untouched in their natural state.

Another notable structure in Kilwa is Husuni Kubwa’s Palace. Although elements of the palace may be traced back to the thirteen- century, most of it was built in the fourteenth century under Sultan al-Hasan ibn Sulaiman’s supervision, who also contributed to creating an addition to the neighboring Kilwa’s Great Mosque. For unexplained reasons, the mansion was only occupied for a short time before being deserted before completion.

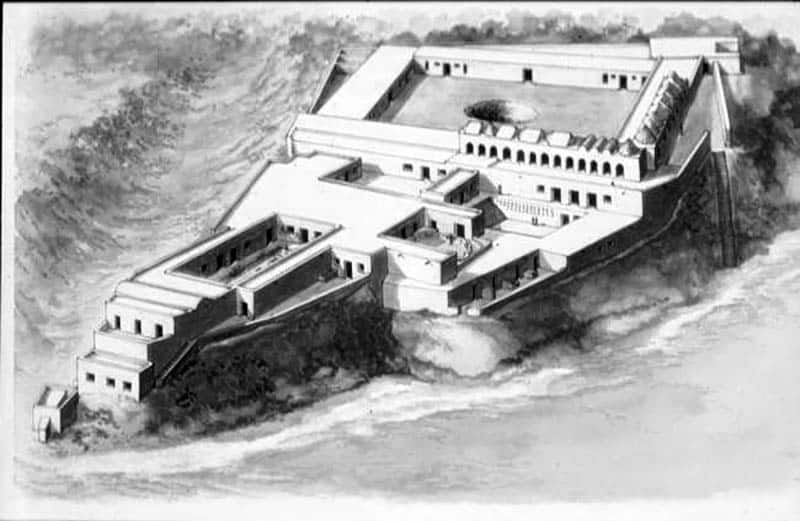

The structure was created out of coral stones on a high cliff facing the beautiful Indian Ocean in classic Swahili architecture style. There are 3 major components of the palace: a south courtyard primarily for business and a housing area with over a hundred separate bedrooms. And a broad stairway going down to a beach-side mosque.

A pavilion, which was most likely used as a banquet room, and an octagon-shaped swimming pool are two more prominent features. Husuni Kubwa covers a total area of about two acres. Cut stone was utilized for decorative elements; vaults, door jams, and the coral rag was put in a limestone mortar. Most of the rooms were around 3 meters in height. Cut limestone blocks were put across cut timbers for the roof, and white plaster was used for the floors. Husuni Kubwa’s main entrance is from the beach.

China’s celadon was the most common type of foreign glazed pottery found at the site; however, there were also some Ying Ch’ing ceramic sherds as well as one Yuan dynasty flask, all of which were dated to approximately 1300 CE. Husuni Kubwa is a building that neither the Kilwa Diary nor any follow-up Portuguese records mention as being comparable to other facilities at this time.

Husuni Kubwa Architecture

The medieval Husuni Kubwa palace, now in total rubble and built under the supervision of Sultan al-Hasan ibn Sulaiman just at the beginning of the 14th century, was only occupied for a little while before being deserted before completion. Though the city of Kilwa didn’t fall into ruin until 1843, when the last ruler was banished to Muscat, the Husuni palace had been abandoned since the 1400s. Its temporary occupancy and incomplete status disclose a great deal about the construction process and tradition. The remnants of Husuni Kubwa were hidden in dense shrubbery until recent archaeological excavation works were carried out.

The palace sits atop a sandstone bluff with views of the Indian Sea eastwards, the city of Kilwa located to the west, and the Kilwa harbor entrance to the north. Its brief popularity was due to its exquisite architecture, with over a hundred bedrooms and terraces arranged around sunken gardens that stretched down a cliffside. The vast South Courts, the residential building encircling four central courtyards, and the steps going down to the shore at the cliff’s edge are the three main aspects that situate the castle across the ridge.

Its status as the most impressive royal house located southward of the Sahara desert dated well before the 18th century is based on features such as a sizable octagonal-shape pool and a southern mercantile court emphasized by an eclectic roof-line. The name of the palace complex comes from the Arabic word husuni, which means ‘’fortified enclosure’’, as well as its location as ‘’kubwa’’, or the Biggest of 2 husuni. The Husuni Ndogo, a strange rectangular bulwark about 80 meters east of the palace, is the minor husuni.

Husuni Kubwa South Court

The enormous south courtyard is forty-six by forty-six m, surrounded by around thirty-eight storerooms, two deep, with two units of 4-6 comparable closets on each side. Each flank of the south courtyard has an entrance in the middle, including 1[one] on the northern side that leads directly to the inner castle. Long chambers that run around twenty meters[20M] to the corners surround the stepped entries into the court on the western edge and the edge adjacent to it. These lengthy chambers are accessible to the court by tall square windows and a doorway, as well as low, narrowing windows that might be used as secondary doorways. These lengthy rooms, as well as the more partitioned rooms along the east and south sides, were flanked by smaller segmented storage chambers, some of which had sunken floor levels 1.5 m underneath the front bedrooms, necessitating the use of a ladder. The back chambers are only lit by eight squared[8sq] portholes measuring forty centimeters by forty centimeters, a pair on both walls, which could have also acted as storage holes. Unlike the more secluded staggered doorways throughout the palace, the entrances to the storage rooms are precisely aligned with the exits (or secondary entrances) from the Southern Court, rendering the doors more approachable. Although a dual-apse niche on the east side of the Southern Court implies that this room may have also been used for community Friday prayers, these design aspects suggest that this courtyard was likely a significant center of trade and business in the palace.

Upper Storey Apartments of South Court

From the well-built western entry to the north, the 2nd level of apartments extends from the northern access to the west, and both levels come together at the northwestern side of the quadrangle. A short parapet surrounds them, ensuring solitude from below, while lofty arches allow for expansive views of the surrounding countryside. They were apparently meant to enclose the entire court and were likely reserved for prestigious merchant tourists to stay in. The palace’s skyline is distinguishable from the surrounding buildings by the roof terraces. These rooms each feature a distinctive mixture of vaulting, starting from basic barrel vaults to more Complex vaults that are additionally supported by quarter, octagonal, or conical vaults. At the corner of these two diverse-vaulted arms is an intersectional room with a tall conical dome with fluted interior and ribbed exterior. In its heyday, the steep edges of this pyramid at an inclination of around 60 degrees give this vault the appearance of being a spire, making the roof the tallest\highest roof in Husuni Kubwa.

South of the courtyard is an expansion that appears to have been 2-floors and was likely used as a home for a court administrator in charge of Commence. The rooms were small but beautifully furnished with carved embellishments and coral doorjambs in this building. Taxes may have been collected here because it was the town’s most accessible location. Each side of the large well was 4.6 meters long, located next to this home, and was built within a mangrove pole structure coated in masonry.

Inner Core

Coastal homes in East Africa may have inspired this architecture in the palace’s residential portion. Private rooms are clustered around an enclosed courtyard in the north and an adjacent court for events in the south. When it comes to Husuni Kubwa’s palatial complex, the four-court layout follows the same pattern: The westernmost courtyard acts as a listening court that connects to the domestic and bathing courts with a pool both located east and north, respectively. And the northeastern courtyard serves as a private palace court.

Audience Court

The 13-by-15-meter Audience law court appears depressed when entering from the west because of the high intimidating walls that encircle it on all sides. There is an impressive walkway just above the rooftops of the surrounding rooms that extends from the south, west, and north of the building. Three columns of tiny square niches can be found on these walls, which are likely for decorations or for holding lamps. For citizens who come to beg the emperor or his representatives, two large verandas break the wall surface that otherwise consists of rooms. In the Audience Tribunal, a lower realm is depicted by the pavilion to its east. The Audience law court, which extends northward to the pool or eastward to a pavilion that leads to the Domestic law Court, is also the westernmost law court.

Pavilion

The eastern corner of the Audience law court has nine stairs leading to a pavilion that is 3- feet above the ground. With its massive elevation and the broad slab of possibly a reclining podium (marked by a twin niche), this pavilion was probably the Sultan’s reception room. “To the east, the port could be seen, while to the west, the city of Kilwa could be seen behind the lower Audience law court. Cross-breezes were possible because of the large door and window openings. At the pavilion’s southernmost tip, you’ll find a series of unique domed rooms that looked out over the South Court.

Domestic Court

The Domestic law court, eastern of the pavilion, is named because it features a deep well and is surrounded by servants’ quarters to the south, east, and north by residential apartments. The court is just approximately 40 cm deep, substantially simplistic than the Audience law court. A few sleeping rooms are placed to the east, one of which has a built-in bed frame and accessibility to a sitting veranda adjacent to the primary well and reservoir.

Residential Rooms

The structure of the residential chambers located north of the Domestic law court is matched by even more residential rooms located north, which directly faces the Palace Court’s inner section. The royal domicile’s core comprises two sets of interconnecting suites. Each double-apartment unit starts on the corresponding court, with the units progressing from a brief but extremely broad ante-room [approximately 17 m in length] into the main entrance room and then to 2-bedrooms, both measuring around 2.2 m sq. These two suites are linked to the other unit’s suites. These units are connected by a central hallway and a common entrance on the western end of the principal rooms. Shelves and Niches, as well as possible wall hangings, adorned these flat-roofed spaces. Both the public lobby and the northern anti-room off the royal court open onto a portion of the castle with latrines that opened out throughout the western cliff and 2- levels of workers quarters with big built-in platforms that may have functioned as communal sleeping beds. The residential rooms located eastward also have access to the bathing area, which has a unique pool.

Swimming Pool

The swimming area is surrounded by an enclosed arcade and is located within a 13-meter square open court. The pool is octagonal in shape and has an eight-meter diameter. The pool’s corners are filled with triangular lobed niches that likely act as seats, and the edges are characterized by semicircular apses that provide access to the pool. The pool’s edge is roughly 60 centimeters above the surrounding ground, and its depth varies from 2 m on the eastern side to 1.6 m on the western side. A drain goes to the cliff from the west side of the pool to let out. Two sheets of plaster are used to seal the area.

Palace Court

The last and most private courtroom is a rectangle extended along the north and the south axis at the north end of the castle. The south and north ends of the palace court are recessed to about 1 m by 4 descending steps, respectively. Raised pathways separated by wide-doored chambers form an Iwan arcade to the east and west. Square apartments mainly accessible by moving upwards from the court can be found at every corner of these arcades. All of these chambers have a dry well draining system in the center of the floor, 100 centimeters deep, circular holes that might have held decorative plants and flowers seen while standing at the court. The arcade’s other rooms are more extended, with smaller chambers branching off to the south and north.

Another series of residential chambers can be found above the royal court. These rooms are similar to those in the domestic law court because they lead from an antechamber to the main chamber and then into two sleeping rooms. However, there is no interconnecting suite of sections behind this northern unity. A Varanda or pavilion may have been built behind these apartments to capture the scenery. Remnant of carved writings and tiles, as well as pieces of curved vaulting showing that the chambers were barrel-vaulted, suggest that this residential part was the most elaborately decorated. This residential structure has moved 1 m east of the palace’s central south-north spine as well as the line of its approaches from the palace tribunal.

Steps of Mosque

A large stairway leads down the northern edge of the peninsula, where a tiny building presumed to be a mosque rests on the beach, from the palace’s most northwest corner. The stairway is carved out of the cliff’s sandstone and drops in two flights, practically at right angles to one another. The stairs are big and uneven, and the edges are covered with wood nosing to prevent deterioration. The tiny structure, which is approximately 2 m wide, has one entrance on the south wall and a low water storage unit on each side. This space is assumed to have been a mosque that is older than the palace because of its size, sea closeness, and straight northward direction. Small mosques with sea views are famous on islands like Kilwa and Zanzibar, where they’re visually accessible to passing mariners and serve as a symbol of reverence for the sea. This tiny structure could have once been used as a stairwell entrance.

Material, Construction, And Decoration

Coral stone is the most common material used in the mosque’s construction. The horizontal strips of the southern court, where the fine walls were built-up in sections as the wall dries up and the lime inside the porous stone solidified, show the control of this substance, whose lime content transforms rapidly to cement. Because of the support capabilities and the weight of this material as a roof covering, most of the chambers in the castle, including the domed ones, aren’t wider than 2.7 or 2.8 meters. Timbers are inserted in the walls around the cornice line in the vaulted chambers in which you can find any columns for reinforcement.

The apartments above the southern court show that the palace has a range of different vaults, although barrel[tunnel] vaulting stands as the most prominent type. Quarter vaults support one such tunnel vault, which has a ribbed leaves shape and is supported by twisted pendentives inserted into the walls. The cornice level is formed into an octagonal shape by flattened pendentives that are covered by a frieze of sculpted coral plates in other more traditional barrel vaults. Similar plates of crafted coral from offshore lined the more spectacular vaults.

Coral stones were hand-set into the thick lime plasters into the walls to add strength. The exterior was then polished in royal residences and reception areas but left uneven in other rooms, presumably those of the laborers, to ensure the trowel stokes could be seen.

Plaster flooring was typically laid over crushed coral or simply compacted red earth. Soakaways, 100 centimeters deep, circular holes cut deep into the sandstone underlying soil and pilaster with coral bricks, are carved into the center of Husuni Kubwa’s domestic rooms, through which water might drain. Occasionally, these drainage holes were sealed with coral slabs, sandstone, and a 4-centimeter hole drilled through them.

Most of the designs at Husuni Kubwa are distinctive to the EA coast, crafted out of offshore living coral. The chambers at the palace’s northern end are the most fancily decorated. Carved coral plates were inlaid on the doorjambs, cornices, dadoes, as well as gabled ends of Tunnel vaults in these chambers. One of these dados is made out of interlocking crosses that form an 8-pointed star shape. Two deeply engraved coral bosses in the main section of these apartments represent a star encircled by semicircular petals as well as a pinwheel design. The uniqueness of a frieze of squared frames with a dart design is that it is made of both coral and plaster. Three structures with markings were also discovered in some of the rooms: one requesting God’s protection for the Sultan called Al-Hasan ibn Sulaiman al-Mali al-Mansard, another wishing the building’s occupants well. And a third depicting intricate foliage intertwined with writing that has yet to be translated.

Other architectural themes found throughout the castle include a herringbone wire design wrapping around edges, fleur-de-lys pictures, and semi-circular moldings that mimic the palace’s arcades of vaults. Many of the beautiful carvings on tiles and bosses look to be incomplete.

For more articles related to Tourist Attractions in Tanzania click here!