Gogo People – History, Economy, Traditional Society and More

The Gogo people also known as Gongwe tribe are a Bantu linguistic and ethnic group found in the Dodoma Region of central Tanzania. The Gogo people were estimated to be 1.3 million in number as of 1992. Historically, the Gogo people have been mainly pastoralist and patrilineal. However, many modern Gogo now practise settled agriculture; some have moved to urban areas, while others work on plantations across Tanzania.

History of the Wagogo Dodoma

Nyamwezi caravans moving through the area while it was still a frontier domain invented their name during the 19th century. Richard F. Burton claimed only a small population for it, proclaiming that one could walk for 14 days and only find scattered Tembes. There remains the problem of insufficient rain for humans and crops because the rainy season was short and erratic. As a result, the area experienced frequent drought. In the 18th century, the Gogo people were majorly pioneering colonialists from Uhehe (the land of the Hehe people) and Unyamwezi and are often confused with the Kaguru and the Sandawe. Fifty percent of the ruling group came from Uhehe. They had a long tradition of hunting and gathering, thereby allowing the Nyamwezi to transport the ivory to the coast. Although they had become cattle-owning agriculturalists by 1890, they continued to have low regard for tilling the land and are said to have maltreated their agricultural slaves.

The Gogo people experienced famine in 1885, 1881, 1888 to 1889 (prior to the arrival of Stokes’ caravan), 1894 to 1895 and 1913 to 1914. The major reason for the unusual series of famines in Ugogo was the unreliable rainfall and the droughts that followed.

Economy of the Wagogo Tribe

Ugogo has had a mixed economy of herding and agriculture, but most heavily relied on grain gotten from agriculture. Cultivation work parties that traditionally comprise about 20 women and men were held from January to March and lasted all day, with a beer party coming up at the end. People attended from areas less than five miles away. Such people were usually close neighbors. However, agricultural cultivation generally played a secondary role in the livestock cycle.

Since baboons, bush pigs, birds, and warthogs can extensively damage grain, the responsibility of protecting the fields, even at night, fell on boys and men. Many supernatural and medicinal methods were also used to protect the fields against wildlife as well as the evil influence of humans.

The average Gogo people didn’t possess a very large cattle herd in traditional agricultural practices. Though patterns have evolved, it must be noted that the cattle also belonged to clan members, kin, and relatives.

Traditional Society

Social Structure

Wagogo clans moved around a lot, severing ties with older groups and adopting new links and families, new clan names, and new ritual functions. In short, the Gogo people became different from what they used to be.

Although early writers from Europe gave priority to the political chiefs, referring to them as ‘Sultans’ as they do on the coast and also emphasized their collection of the highly profitable taxes on scarce water and food, it was actually the ritual leaders who influenced the entire community. They controlled fertility and rainmaking, medicine for protection against hazards and natural disasters and prevented some resources from being overly utilized. The ritual leaders were not to leave their “country”; they were to be rich in cattle, decide on circumcision and initiation rituals, offer supernatural protection for all undertakings and serve as judges in witchcraft accusations, serious assault, and homicide.

Neighbourliness is highly valued among the Gogo people. After meeting his physical needs, the young men from a homestead would escort a strange traveler many miles in order to place him safely on his way. The homestead was so essential in the Gogo society that a person who died strangely (through a lightning strike or a contagious disease) would be thrown into the bush or the trunk of a baobab tree because such a person had no homestead and could change into an “evil spirit” that associates with witches and sorcerers.

Family

Most brothers among the Gogo people did a lot to help their sisters, who often lived with their brothers during sickness until they recovered because brothers have strong legal and moral obligations to fulfil these duties with the cooperation of the sister’s husband. Even later in life, sisters and brothers continue paying visits to each other because a wife is never fully incorporated into her husband’s group.

Gogo People Marriage

Although the majority of Wagogo men have only one wife at any given time, most found polygyny very attractive. It was the prerogative of older and well-established men. A reasonably rich man could hope to marry two or three wives, and sometimes together.

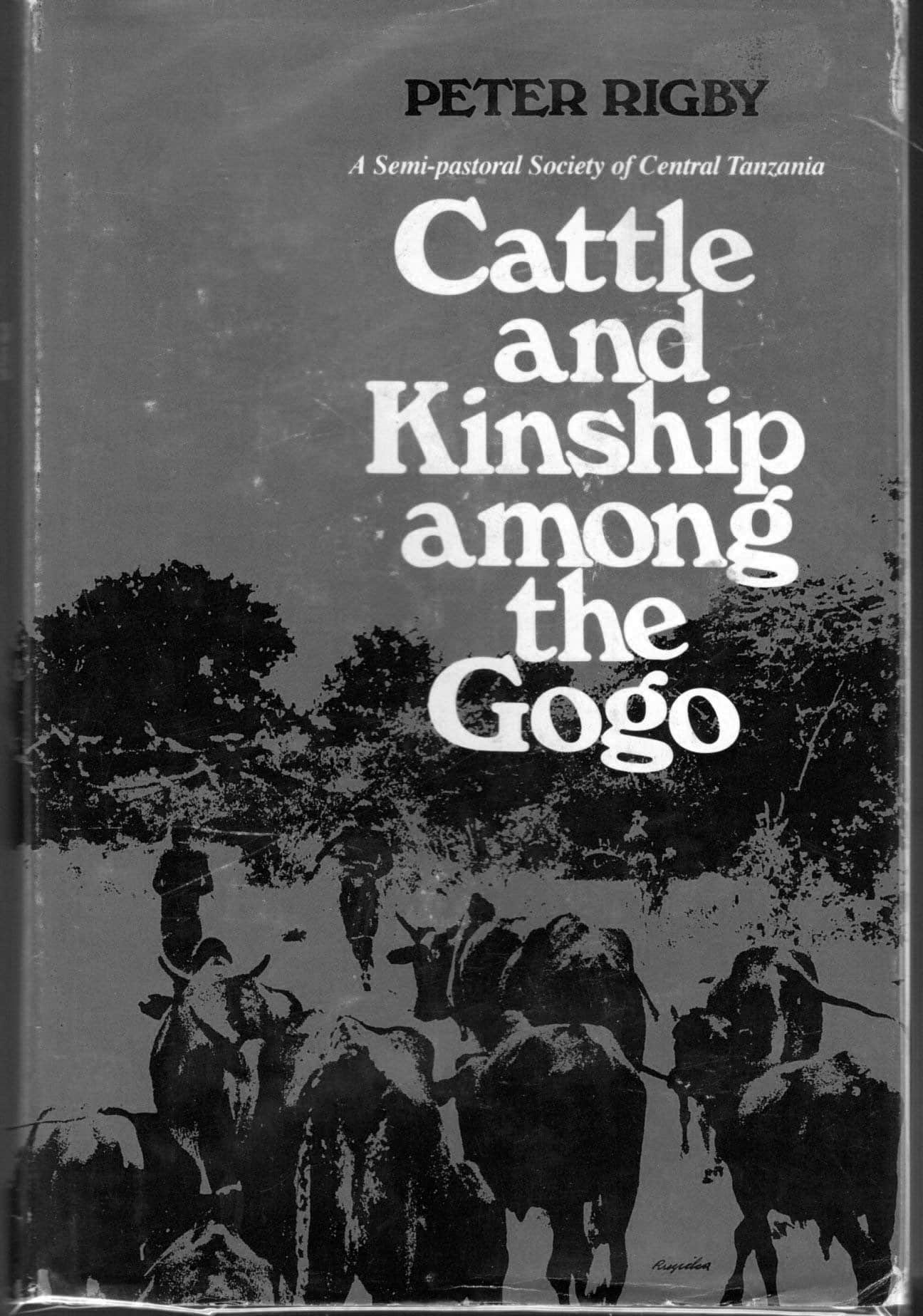

Most marriages by the Gogo people were held within a day after the agreement had been reached on the quantity of livestock to be included in the bride price; only then is the transfer made. Even a century later, bride price is still entirely given in livestock, and a high percentage of court cases involve the return or giving of bride price. After divorce, all children birthed during the marriage belonged to the former husband, from whom the cattle came. “If you marry the child of others, then all the relatives of your wife become your relatives because you’ve married the child and you must love them.” (Rigby’s book – Cattle and Kinship). However, lovers of married women could never claim their child. If a husband had paid the bride price for his wife who was pregnant before marriage, he must still accept ownership of the child.

Defence

Defence against the Maasai, Waheheh, and Kisongo was organised by the Gogo people based on the warriors’ age groups, just like the Maasai. This “military” organization was mainly used for local defence, although it could also be used for cattle raids against others. When an alarm was sounded, all able-bodied men were expected to take up arms and sprint towards the call (this didn’t always work smoothly).

Gogo People Historical Accounts

- They were described as “hongo squeezing Wagogo” by Edward Hore in 1878

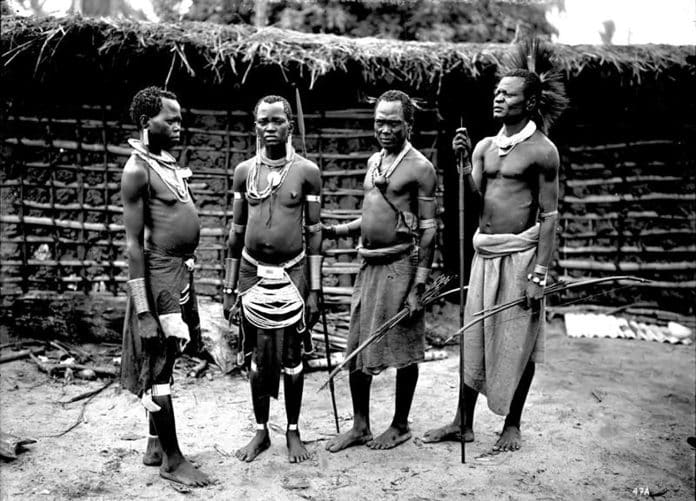

- They were greatly admired for their cattle and physique by the Germans. Otherwise, they agreed with Edward Hore, Henry Stanley, and Emin Pasha. The British, 30 years later, also found the Wagogo people “uninterested in progress.”

- Henry Morton Stanley wrote in his book In Darkest Africa while trying to bring Emin Pasha to the coast

“We got to Muhalala on the 26th, and on November 8, we had passed through Ugogo. There’s no other country in Africa that has piqued my interest more than this. It is a ferment of distraction and trouble and a rat’s nest of petty annoyances that beset travellers daily while in it. No natives know so well how to aggrieve and be unpleasant to travelers. One might think a school existed in Ugogo where vicious malice and low cunning were taught to the chiefs who were masters in the foxy craft. I gazed at this land and its people with desiring eyes 19 years ago. In it, I saw a field worth the effort to reclaim. In 6 months, I was sure Ugogo could be made orderly and lovely, a blessing to strangers and inhabitants, without any great trouble or expense. It would turn out to be a pleasant highway of human interaction with faraway people, providing wealth to the natives and comfort to caravans. On arrival in Ugogo, I learnt that I was debarred from that hope forever. It is the Germans’ destiny to carry out this work, and I envy them. The worst news is that I will never be able to extinguish the insolence of the chiefs of the Gogo people, rid this cesspool of iniquitous passion, and make the land healthy, clean and beautiful. While I wish the Germans good luck, my mind is full of doubt that it will ever be the fair land of welcome and rest I had dreamed of making it.”

Prominent Gogo People

The Gogo people have produced some big names in Wagogo music, Tanzanian politics, and society in general.

- Godfrey M. Mhogolo – first Tanzanian bishop to ordain women and spearheaded their development in the church he was also the longest-serving bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Central Tanganyika, having served between 1989 and 2014

- Hukwe Ubi Zawose (1838 to 2003), Musician

- Yohana Madinda, first-ever African bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Central Tanganyika

- John Mtangoo, musician

- Mzee M. Malogo, musician and leader of the Nyati group from Nzali

- Hezekiah Chibulunje, a former member of the parliament and ex-Deputy Minister

- Job Lusinde, ambassador and politician

- John Malecela, politician and ex-PM

- William J. Kusila Politician and MP

- Mzee Pancras Ndejembi, Politician

- Frederick Chiwanga, Diplomat, Editor, Lecturer, Interpreter and Translator (Kigogo, Kiswahili, English, French), Sokoine University of Agriculture

- John Chiligati, ex-MP and former Minister

- Patrick Balisidya, Musician

- Simon Chiwanga, ex-Chairman of the Anglican Consultative Council and retired bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Mpwapwa

- Kedmon Mapanha, Lecturer II at the University of Dar es Salaam

- Simon Chiwanga, Toxicology and Public Health researcher; currently serves as the Programme manager – Malaria and Child Health in PSI, Tanzania, water sanitation and hygiene expert and activist, environmental management scientist. He is a Theologian and also Canon of the Anglican Church of Tanzania, member of the synod of the Diocese of Mara and gospel musician

- Palamagamba John A.M. Kabudi, MP and the Minister for Constitutional Affairs and Justice and professor of law

- Emmanuel Mbennah, an accomplished academic, has two earned PhDs, former International Director of Africa Region for TWR International. He has been the VC of St. John’s University of Tanzania since September 2014.

- Frank Menda, Lecturer II at the University of Dodoma

- Emmanuel Chidong’oi, Founder and MD – Tanzania Organisation for Agricultural Development, first president of Ecosystem-based Adaptation for Food Security Assembly Tanzania, coordinator Eastern Africa Agriculture Practitioners’ Organisation, MD Tanzania Initiative for Development effectiveness, member Global CSOs partnership for Development effectiveness – Working Group on Conflict and Fragility

- Christopher M. Nyawamanji, MBA holder from Mzumbe University, Chairman of Tabora-based SUDESO, and Development Facilitator

- Engineer Raphael P. Menda, founder and president of CoYESA Company Limited, an expert in civil, land, ICT, architectural, dam and borehole drilling technology

- Benard M.P. Mnyang’anga, popularly known as Ben Pol, musician

- Bahati R. Chinyelle, financial analyst and accountant, ophthalmologist, Gogo, Kiswahili, and English translator, founder of YES I DO, and co-founder and Board Chairman of LAUBRINS International Company Limited with extensive local and international experience with HKI, WHO, MoHSW-TZ, SALT, GSM etc.

- Professor Titus A.M. Msagati, professor of environmental and analytical chemistry at the College of Technology, Science, and Engineering, University of South Africa

Last but not the least, the Gogo people have their own Wagogo music festival that happens annually in Tanzania, it is very popular.

For more articles on the Tanzania Tribes click here!