The Short History of Tanganyika Sovereign State

The Beginning

Until the late 1800s, Africans were migrating to Tanganyika which had a small population scattered from the west, south and north. By the middle of the century the old and newer groups of people were already established in recognizable tribal societies, each with its own social and political structure, language, and traditions, but also with similarities built on interaction and perspective, marriages and trade on productive exchanges of goods and services. These tribes numbered about one hundred and twenty in total although some of them were very small, with hundreds of people, while the larger ones had hundreds of thousands of people. On one side were a few small self-governing states; on the other hand there were small administrations in which, although the largest influential community was recognized, all authority was operated only at the village level. Some regimes were dictatorial, but most had elements of participatory democracy, with

elements of independent governance. Since there was no shortage of land, tribal disputes were fewer than previously thought; dialogue was a measure, and acts of hostility were often more cultural related than conflicts with bloodshed. That said, there were some unique circumstances; for example, the Ngoni, rising from southern Africa, who were using Zulu weapons and tactics, destroyed the southwestern area until the 1890s, situation which was similar when it came to the Maasai who were also in a state of constant war with their neighbors in the area of north-east.

The Arab Trade and Sultan’s Influence

The biggest threat to stability came from outside, following the improvement of Arab trade towards the interior due to the movement of Sultan Seyyid Said of Muscat early in the Nineteenth Century. Before the arrival of the Portuguese in the Sixteenth Century there was already a thriving trade through Arab ports on the east coast, including the slave trade for domestic service in the Middle East. Inspired by the use of slaves on the Portuguese farms in Mozambique, who were later transported to the West Indies and French colonies in the Indian Ocean, Sultan Seyyid followed the practice, and simultaneously built the already running ivory trade aggressively. However, the biggest profits came from the slave trade, and in 1840 he moved his residence to Zanzibar. In the third quarter of the 19th century, slaves were also employed on large Arab farms in the coastal region, and in Zanzibar.

The slave trade in Tanganyika was relatively small, although it was enough to bring about ethnic animosity. Many slaves were captured or bought in the Lake Nyasa (Lake Malawi) area of eastern Congo; those of the area in eastern Congo were forced to walk to the coast via Tabora to Bagamoyo, at the same time a small road went down to Pangani. What further disturbed the indigenous communities that were still entrenched in the interior of the plains of Tanganyika, and the relations between them, was clear politics in controlling these trade routes with the surrounding country. At the final stage, though not quite the end, being controlled by Arab and Swahili traders in the coastal area; they sought protection and cooperation, and the tribes alongside the road demanded compensation, a situation that led to a change in treaties, cooperation, and tribal wars as different parties fought for the benefit of the region. After the 1850s the situation worsened as imported weapons became more readily available. Thus it was that early European explorers and businessmen reported in a common manner, albeit not on a global scale, about the unrest in civil society. At the same time Zanzibar was withdrawn from Muscat, and its Sultan claimed and effectively controlled much of the coastline from northern Kenya to Mozambique. By the last quarter of the century the commercial interests of Europe and America had flourished in Zanzibar, not in the slave trade but in the pursuit of export goods and the promotion of a new market. In this context cheap cotton fabrics from India had a negative impact on domestic textile production; The final blow came in the form of cheap cotton fabrics from American factories, imports known in Swahili language vocabulary as “American”. By this time, too, a large number of Indians had established themselves as traders in coastal cities, and by the middle of the 20th century the Indians dominated the retail trade and large amounts of wholesale trade throughout East Africa.

Tanganyika Under British Control

German East Africa

For much of the Nineteenth Century, the British were determined to use their power throughout East Africa through their influence via the

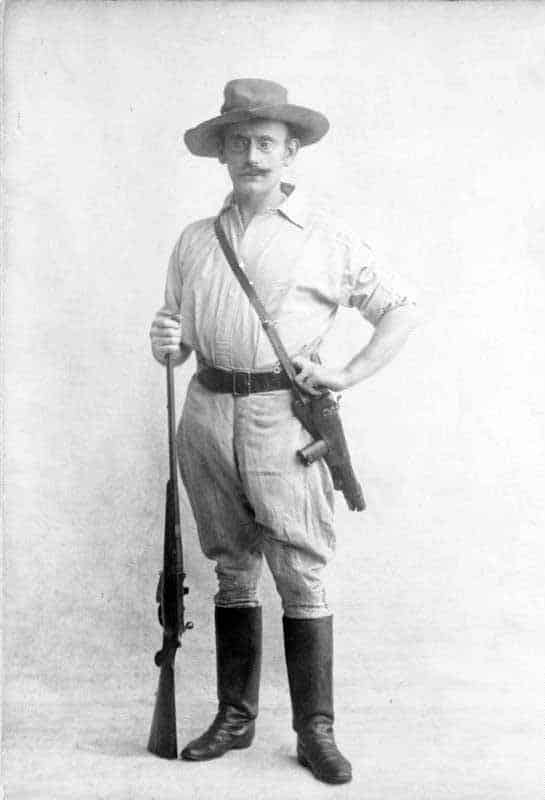

Sultan of Zanzibar. The Arab island owned large parts of the continent to support their slave trade and ivory trade. The British were surprised by the many secret and shady deals of Dr. Carl Peters of the German East African Company when the Germans were pushing to enter the British colonial administration aggressively. Thereafter, the German government, under Bismarck, was involved in taking over Arab opposition to their expanded trade, whereby the Sultan of Zanzibar was forced to relinquish his sovereignty to coastal areas that soon became German East Africa. Carl Peters was eventually rewarded for his efforts for awarding German East Africa a prize through his company in 1890. Penetration and settlement in the interior was difficult, and arbitration was not completed until the end of the century when the Hehe were overthrown under their Chief Mkwawa. Peace was short-lived, and in the years 1907-8 the south-southwest erupted with the outbreak of the Cold War, which was extinguished with blatant violence. German rule in Tanganyika always had a strong military flavor, and was based on the permanent presence of German-led African forces.

Despite the reputation of perfection and efficiency, this German colonial trade was still in a lot of challenges when war broke out in 1914; The worst part of this is, the largest and most expensive development agency, the railway from Dar es Salaam to Kigoma on Lake Tanganyika, was completed only a short time prior. World War I made Tanganyika as a battlefield. The British were quick to invade and seize all the German colonies overseas. However, the German commander in Tanganyika proved to be more difficult to defeat than it was in other colonial war zones. Paul von Lettow Vorbeck fought in a very powerful guerrilla warfare campaign. He captured much of Britain’s vast resources in a very disturbing campaign that swept across East and Central Africa throughout the war. In fact, he surrendered only after it became clear to him that the Germans had already signed a ceasefire agreement. Tanganyika was therefore the area of British conquest and Britain was given control over the country as a League of Nations Mandate. There was a certain amount of map redrawing that resulted with the creation of Rwanda-Belgium border and the Mozambique-Portugal border.

Tanganyika as a British Colony

After the war, the responsibility of ruling German East Africa, was handed over to Britain under the League of Nations Mandate, a fact not associated with Britain being on the side of victory. Several credible proposals were made by giving new names to the available region, but fortunately the Colonial Secretary insisted on having a non-controversial name; for the first time he introduced the name of the Tanganyika Protectorate, and soon the name was changed to Tanganyika Territory. The terms of this mandate stated that ‘until the natives can stand on their own two feet under the difficult conditions of the modern world … the prosperity of the state and property as well as the development of the inhabitants of this country form a sacred trust of civilization’; in other words a trust to be controlled by the League and the governing authorities. Nothing was clarified about how quickly the inhabitants of Tanganyika could expect to be able to stand on their own two feet; the principle of departure of colonialism was finally established, but its time was not indicated on the agenda. The League doctrine, which was largely drafted by the UK, was effectively the basis of future policy of British colonies, whereby colonies were being seen as the source of the self-governing States within the British Commonwealth.

During the Mandate period the existence of colonies and protectorates was considered normal, and its legitimacy was not an important issue; in this context the expectations of the British Federal Government were moderate. Economic expansion in the middle of the war was not consistent, caused in part by the effects of the post-World War I and the Great Depression of the 1930s, but also by the notion of the time that economic development was the work of private capital, not of the state (Tip: example of this was the “Tanganyika Groundnut Scheme“). It was also British policy that dependent countries should, as far as possible, be financially self-sufficient. This combination of conditions meant that the promises of material and social development that were mentioned before were diminished by the small revenue generated by the Tanganyika Government. This was not enough for the task on the table, and progress was slow.

In a more positive light, a system of civil government was established which was capable of development through more modern and democratic means; and at the district level, local government was built on indirect rule, in which, to varying degrees, the authorities passed through indigenous institutions and structures, under the guidance of colonial officials. This system had been established on a voluntary basis in Nigeria and Uganda and allowed the small administration to control large areas that were often overcrowded. It was considered a low-cost government system. As Sir Donald Cameron, the former governor, said ‘We cannot fulfill our responsibilities (under the mandate) if we do not teach the people the art of governance, [and] govern their own affairs … the wise and practical course is to build on… institutions within ethnic groups that have been entrenched for centuries. It is our responsibility to do everything in our power to nurture the local politically on the basis of the social standards in which he lives … It is important (for indirect rule) that the government governs through these institutions which are viewed as an integral part of government, with well-defined powers and functions recognized by law, which are not dependent on the responsibilities of the executive officer … ‘In practice, indigenous institutions were in a few areas created by the innovations of Arab and German rule, while in some areas they were not formal enough for the modern government and had to be redesigned for convenience sake. Perhaps the most foolish reason for the liberation of Africans was the poverty in the colony. The previous German colonists had shamelessly used this country for everything they could and had initiated genocides that wipe a large part of the population. As a result Tanganyika had a very weak economy. It was able to attract small investments but capitalized white settlers were more persuaded to go to the colonies that allowed white settler rule. The economic downturn of the 1930s and its impact on commodity prices did not help the situation either. The northern highlands of this colony were capable of growing some commercial crops, but the southern region seemed unsuitable for large-scale agriculture.

The effects of World War II were inevitable for all forms of development, but from 1946 onwards there was a rapid pace, reflecting the spirit of the Colonial Development and Welfare Act, adopted by the British Government as an act of faith in the days of darkness of the 1940s. This law recognized the future role of HMG in actively promoting the development and disbursement of funding from the HM Fund. A notable increase in training administrative officers and specialists to provide service for the Tanganyika Government was seen, additionally there was a significant education expansion and other types of social welfare, as well as the economy, in the postwar years.

Even the failure of the Peanuts Program, designed in Westminster and implemented by the Overseas Food Corporation, had the advantage of investing in local economies and funds.

Nationalism and the Start of a Modern History of Tanganyika

The post-war world was also a period of hope for African patriots and various liberation movements. India was granted its independence in 1947 and Africans hoped that such liberation could be achieved on their continent also. Initially, Britain’s plans for less-developed African colonies seemed to emerge slowly. It would have taken another 10 years before the Golden Coast region gained its independence as Ghana. Nigeria was not far behind in gaining its independence. These were examples of economies that were relatively successful at least by colonial standards. The British government as a whole was content to give independence to the appropriate political units although it took precautionary measures to avoid holding non-economical colonies at the end of this process. Tanganyika was fully included in this second group. The British therefore proposed the creation of major federal political units. They formed the East African Federation of Britain in the 1950s which included Kenya, Tanganyika and Uganda. Many black Africans were concerned that this was a plan designed to prolong colonial rule. Although the plan collapsed mainly due to the Mau Mau insurgency violence in northern Kenya.

Another major change, which was the direct result of the war, was the United Nations Trusteeship to replace the former League Mandate. This was welcomed by the small political class of Tanganyika as an object of interest, as was the expectation of the United Nations Mission to visit the country for three years to report on various aspects of the British Trusteeship. This radical UN position went hand in hand with the growth of the indigenous political movement, which in turn was motivated by the participation of Africans in the struggle for democracy against the dictatorship of Axis, by views of the American and the Eastern bloc countries against colonialism, and certainly the attainment of independence in India and Pakistan in a year 1947. For many years there had been tribal associations that were primarily concerned with local development, culture, prosperity, and self-help, but which also had a political agenda that could be nurtured and developed. In the middle, the former Tanganyika African Association (TAA) gave way to the powerful Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), under the leadership of a very influential young man, Julius Nyerere in 1954.

In the same year a UN delegation visiting the country defended talks about a timetable to provide independence after more than 25 years. The British government at the time stated that since this country would probably not be ready for independence by the end of the century, the proposal that seemed pre-mature, was refused. Given that the vast majority of the rural population – more than ninety percent of the population – were dissatisfied and showed little sign of co-operation with minority demands for early independence, the rejection of the UN proposal was not generally reasonable. But the direct refusal to even discuss the issue showed a lack of creativity and political competence. This situation led to international criticism, which gave TANU the right weapons to push its agenda, which sparked several years of unnecessary friction between TANU and the Government – and its officials in that regard. The Governor’s plan, Sir Edward Twining, on the equality of power between Africans, Asians and Europeans, had to be abandoned due to the fierce hostility of Africans. Nyerere did not want a mixed-race government; it had to be non-racial. He was basically right, though correctly forgotten that TANU itself for several years was open to Africans only, and that its propaganda – especially in the states – was later increasingly racist.

In 1958 the new Governor, Sir Richard Turnbull, quickly established a joint agreement with Nyerere, who recognized the position of unilateralism. He also observed, following a partial election the same year, that TANU had a clear monopoly in its opposition to the colonial government; it had no real political opponents to compete with. The talks in 1959 were accompanied by the threat of general strikes and civil unrest, leading to the appointment of a fifth elected minister, and the promise of a general election in September 1960. This was followed by an independent local government, with a majority of elected ministers. More than five years after HMG rejected the UN proposal, TANU was elected by a large majority of people, winning seventy-one seats. To what extent the voters were partially affected by the threats, and by the demand to be on the winning side, it will never be known; but voters registered a joint parliamentary vote with the government led by Julius Nyerere.

At the same time separate and extended talks were taking place between the Governor, the Colonial Office, and two successive Colonial Secretaries (Alan Lennox Boyd and Ian Macleod) on progress towards independence, with a target date between 1962 to 1968. Early withdrawal would ensure good intentions for public and the cooperation of a moderate and respected leader. On the contrary, the delay intended to allow African ministers and senior officials to gain experience could have led to a rebellion led by politicians who were more radical than Nyerere, and secretly armed by the Communist bloc. In a broader sense, the Conservative regime suddenly abandoned its colonial responsibilities and its costs associated with those responsibilities as well as their struggles. After the Gold Coast and the departure of Somalia, and shortly after Nigeria, an easier and more sensible choice was made. After only 15 months in office, Julius Nyerere found himself the Prime Minister of independent Tanganyika. In contrast, Ghana had seven years of local rule before independence. At midnight on December 9, 1961, the Union flag was lowered and replaced by a new national, black, green, and gold flag.

After independence Tanganyika (following a union with Zanzibar in 1964, Tanzania) achieved three decades of one-party rule and an African socialism similar to Marx’s politics before moving on to market economy and multi-party politics. It has been the recipient of most aid, the population has more than tripled, and is still one of the poorest countries in Africa. But it removed Idi Amin from Uganda unassisted, and it is to its credit that despite its size it has stayed intact, and peacefully changed the government from time to time without resorting to military coups or reforms. Explore our other article “Profile of the Country Tanzania in All Aspects” to learn more about the country that followed Tanganyika which provides the history of union between Tanganyika and Zanzibar.

For more articles about Tanganyika click here!