‘Uganga’ During the Colonial Period

Anglo-German Agreement of 1889

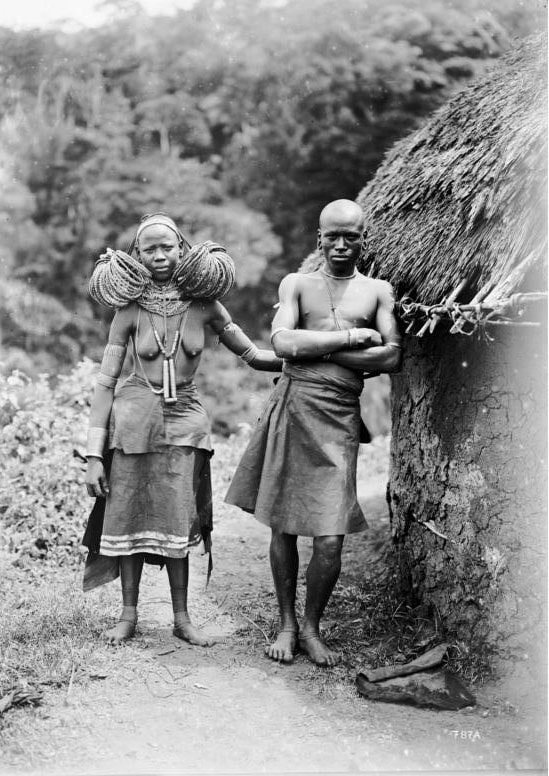

By the Anglo-German agreement of 1889, Germany was given control over the area north of Lake Malawi and East of Lake Tanganyika. Britain closed some lakes. During German rule, African healers (traditional medicine practitioners who used “Uganga”, an indigenous African medical process to heal people) whose authority threatened German independence were prosecuted; and others killed. The Germans destroyed the Shambaa healers’ control system in the North East over health conditions, except for a few who that could be tucked away from the spotlight. For the Shambaa these changes had severe backlash as effects of diseases changed and became a disaster for a large number of people. In 1890, large areas of irrigated agriculture in Tanzania in the Usambara Mountains of

Lushoto district dried up when German farmers took over land in Tanga Region. The Germans forced the natives (Shambaa) to work in areas with malaria that were being avoided and the division of labor changed also. Men were sent away as slaves or servants for Germans, women and the elderly ensured food production. Since the colonial system imposed the responsibility of producing food to women without providing financial assistance to them in terms of medical services, the German government encouraged missionaries to fill the gaps left by the government. Although it was the urban centers that received this service but they failed to succeed because of the world war that was expected to occur.

The Maji Maji War Contribution to Uganga

In some occupied territories, the Germans did not use force to bring about change, since most of them did not live in those areas. However the existing German rule was felt by all people including the Hehe and Ngoni. Waganga in the North were often threaten as they were considered as potential group of people that can start a rebellion like the 1905-1907 Maji Maji War. The famous Maji Maji was led by a Hehe chief who left the Germans in a state of shock. The word “Maji” means water and was coined by a medicinal man, who was said to be in the form of a scary animal living in the Rufiji River, administered the medicine – in a mixture of corn, water and sorghum seeds – that provided protection against disease, hunger and all kinds of evil if it is swallowed or sprinkled on a person. The message also spread that this medicine had the ability to turn bullets fired by the Germans into water. The Cold War was ended by the Germans who showed that the widespread message to be untrue. The evil act of revenge began to appear. All the villagers living in the South East of the country who took part in the war, their huts and food crops were destroyed by the Germans. The report shows the loss of more than 100,000 (Explore our other article “Role and History of Uganga – The Exchange of Magical and Indigenous Healing” to learn more about the history and different roles “Uganga” played in Tanzania).

Colonialists Deliberate Measures in Controlling Uganga

In 1909, the Germans began to control the healers through officers who issued certificates stating the disease treated, the payment and the location of the service. Several years later, during the German occupation of the area, World War I began (WW1 1914). Within that year, the Tanganyika colony was one of the war zones. All areas in the colony suffered from the devastation caused by the fighting between Germany and the British, who were supported by Indians and troops from South Africa. Eventually, Britain won and sliced the new territory called Tanganyika into eleven states. Although colonial policy was varied often, colonialists generally did not want Uganga to interfere in matters of independence or public law. Under British rule, the law of magic in 1922 did not allow anyone to practice Uganga with the intention of using magic. In 1925, Britain established an indirect rule through the hereditary monarchy. The goal of Britain was to use the chiefs to gain the trust of their citizens. In the case of indigenous healing and health care, the implication of the indirect rule was that only rainfall making practices were permissible. Almost all other forms of Uganga were rejected, as they were believed to include other forms of magic and sorcery.

In general, the breakdown of African unity in controlling the health sector had a very negative backlash, the impact was not small because the control of traditional or the overall indigenous healing was made illegal. At that time, tribal leaders and healers lost the ability to combat the bad habits in society. Opponents of witchcraft and Uganga continue to grow in numbers throughout the whole Tanganyika during the British rule (1919-1961). These folks were specialists in finding witches or protecting the innocent. The Government‘s response was counterproductive. On the other hand, there was a fear brought about by the search for witches, which did spread rapidly throughout the Tanganyika territory, which is said to have probably been the major cause of rebellion. Local officials, on the other hand, welcomed the search for

witches to restore peace in the community. However in 1930, the British authorities focused more on nature and the philosophical foundations of natural medicine. Lord Hailey, a “native affairs” specialist came up with an idea of enrolling traditional healers in order to integrate them into the modern medicine in 1933. From this perspective, in the same year, Hailey conducted an African study on indigenous healing practices, and she came to the conclusion that not all Waganga are involved in witchcraft. From then on, the desire for traditional medical services arose with the aim of looking at what they are made of and their benefits, situation that led to the strengthening and growth of the practice of Waganga during the British colonial period. At that time, the UK placed the practices of Waganga under the provisions of the law of the medical experts and dentists (Cap.92.20) that said:

“Nothing contained in this ordinance shall be construed to prohibit, or prevent the practice of systems of therapeutics, according to native methods by persons recognized in the community too which they belong and who are duty trained in such a practice.”

As Uganga continued to flourish in the British era, colonial rule did not interfere with the practice of Uganga unless it led to death. In short, the UK policy on indigenous healthcare was transformed from ‘unhelpful / neglecting’ to ‘tolerant’. So between 1930 and 1950, government clinics and hospitals collaborated together with Waganga. That said, still African health care continued to rely on social law and spiritual powers to define and control events and relationships. But, healing was more focused on the combating and curing perspectives and less focused with social issues. Traditionally the real African healers did not have European counterparts because of the many roles that the Mganga had to conduct in the community.

For more articles on natural remedies (traditional medicines) click here!