The King’s African Rifles Records – History, Uniforms, Formation and More

From 1902 through the 1960s, the King’s African Rifles (KAR) was a multi-unit colonial regiment of the British established from Britain’s different East African colonies. Within the colonies, it played both internal security and military roles, as well as serving beyond these areas during World Wars I and II. Most of the commanders were seconded from the British Army, while the file (askaris) and rank were recruited from the local population. The battalions had several Sudanese officers established in Uganda when the King’s African Rifles was originally raised, and local officers were commissioned near the end of British colonial authority.

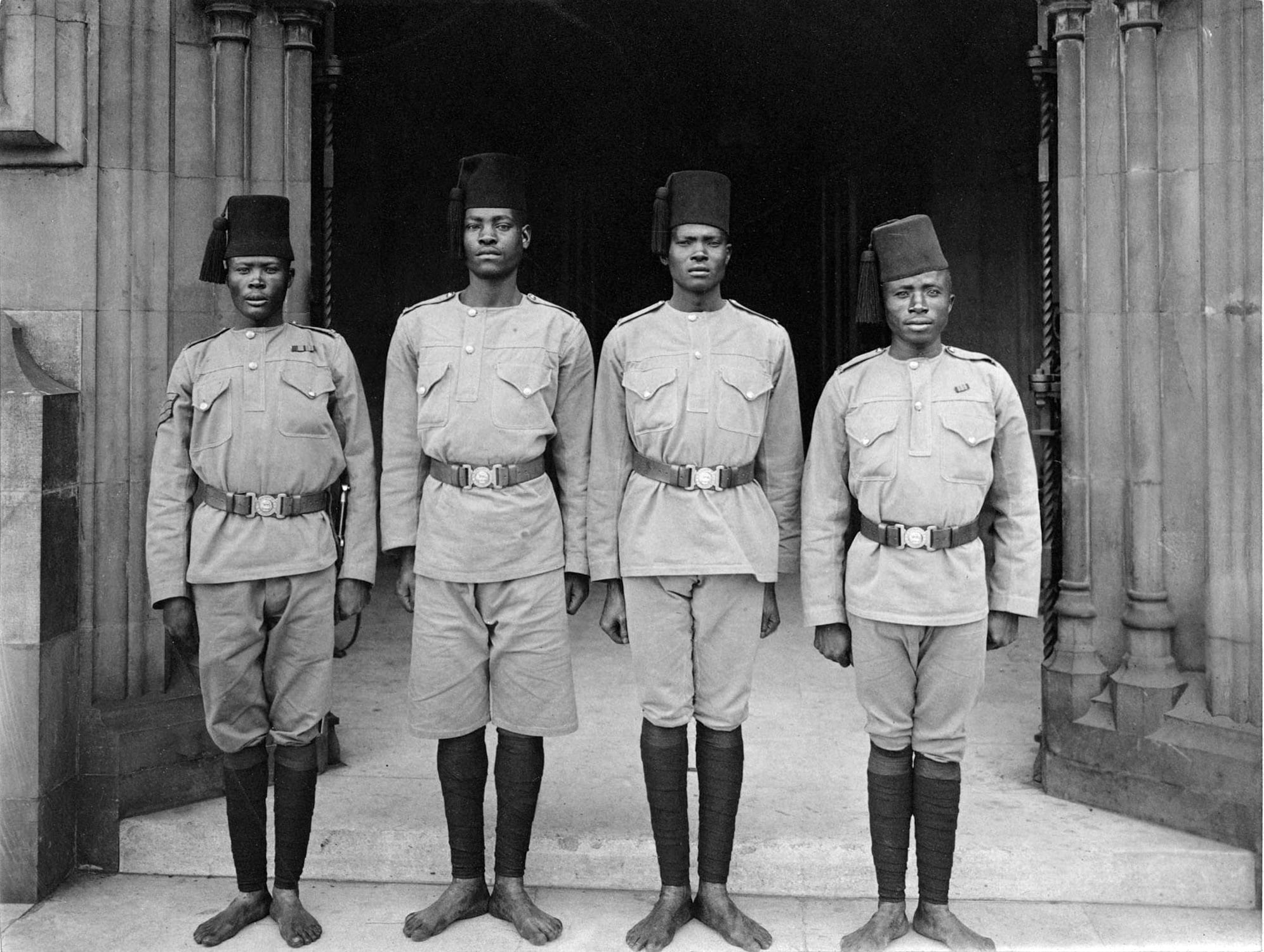

King’s African Rifles Uniform

The King’s African Rifles’ parade dress consisted of khaki drills coupled with cummerbunds and tall fezzes till independence. These were usually red, however, there were minor battalion differences, such as Nyasaland soldiers who wore black fezzes.

The uniforms of field service wore dark blue puttees and jerseys, khaki fez cover, and khaki shorts, with a neck flap and an integral folding fabric peak before 1914. The thick military boots of the time were impractical for African trainees who had never worn any footwear before, therefore Askaris donned sandals or went barefoot. Fezzes were identified by a Roman or Arabic number, which the wartime-raised units wore on geometric-shaped fabric patches. All dark blue uniforms were replaced with khaki counterparts in the Great War, and a pillbox hat (with a King’s African Rifles cap badge / King’s African Rifles insignia on it) covered with khaki was worn during the campaign. A collarless grey-blue angora shirt called “greyback” replaced the khaki shirt post-war. Slouch hats having colored hackles were worn by senior NCOs and officers.

King’s African Rifles’ Formation

In 1902, the East Africa Rifles (EAR), the Central Africa Regiment (CAR), and the Uganda Rifles merged to form six battalions, with one to two battalions stationed in Nyasaland, British Somaliland, Kenya, and Uganda:

- 1st Battalion (Nyasaland) [1902 to 1964] with 8 companies (previously 1CAR)

- 2nd Battalion (Nyasaland) [1902 to 1963] with 6 companies (previously 2CAR)

The first two battalions were called the first and second Central African Battalions.

- 3rd Battalion King’s African Rifles (Kenya) [1902 to 1963] with 7 companies as well as a camel company (Previously the East African Rifles)

- 4th Battalion (Uganda) [1902 to 1962] with 9 companies (Previously the African Companies of the Uganda Rifles)

- 5th Battalion (Uganda) [1902 to 1904] with 4 companies (Previously the Indian Contingent of the Uganda Rifles) — the initial intention was to raise it as the senior battalion.

- 6th Battalion (British Somaliland) [1902 to 1910] was established by 3 infantry companies, the mounted infantry, the camel corps, and the militia of the native forces in British Somaliland.

Apart from an Inspector-General who toured twice per year and gave his report to the foreign office and the customary regimental staff, these six battalions had no regular staff organization when they were formed.

The Colonial Office abolished the 5th and 6th battalions in 1910 as a cost-cutting measure and in response to white-settler concerns over the presence of a significant native military force.

History of King’s African Rifles Operations

Campaigns in Somaliland

The King’s African Rifles fought Diire Guure, the King of Dhulbahante & Darawiish in the early 1900s. On October 6, 1902, Lt-Col. Alexander Cobbe of the 1st Battalion (central Africa) KAR received the Victoria Cross as a reward for his heroics at Erego.

In 1920, Hassan, Diiriye Guure’s emir, and his Dervish organization were destroyed by the British ground and air forces which included the KAR.

During the First World War

The King’s African Rifles WW1 started with 21 tiny companies in 3 battalions (each having up to 8 companies following the pre-1913 establishment of half company by the British): the first Nyasaland (half of this battalion was situated in northeastern Nyasaland), third East Africa (a single company on Zanzibar), and the fourth Uganda, both of which included the fourth platoon of Sudanese officers. Furthermore, the enterprises were dispersed throughout British East Africa.

In 1914, the King’s African Rifles had a total of 70 British officers, 2325 Africans, and 3 British NCOs. They had no organic heavy weapons, organized reserves, or artillery, and the companies were essentially huge platoons of seventy to eighty men.

The King’s African Rifles was extended in 1915 by reorganizing the three battalions into standardized four-company battalions and increasing their size to 1,045 men apiece. Due to white sensitivities about equipping and training a big number of black Africans in Kenya, the 5th Kenya and 2nd Nyasaland battalions [1916 to 1963] were not re-raised until 1916. The second, third, and fourth battalions were later extended into two battalions each by recruiting in their native districts later in 1916. Genuine expansion did not begin until 1917 when General Hoskins (previously King’s African Rifles’ Inspector General) was assigned to lead British East African forces. The first Battalion was increased by two, while the sixth (Tanganyika Territory) Battalion was established from the previous German East Africa‘s Schutztruppe and later doubled as well. The Mafia and Zanzibar armed Constabularies were combined to become the 7th. Many more duplicate battalions were later formed in 1917 when each of the initial 4 battalions (now known as regiments as per British tradition) recruited a third battalion and a fourth or Training Battalion. Recruiting in Uganda allowed the fourth Regiment to establish two further battalions, the fifth and sixth. Mounted Infantry Unit was mounted on camels by KAR, it was initially part of the third regiment, as was the King’s African Rifles Signals Company.

As a result, by late 1918, the King’s African Rifles was made up of 22 battalions:

- Western Force: First King’s African Rifles Regiment, First, Second, and third Battalions; 4th King’s African Rifles Regiment, first and second Battalions

- Eastern Force: first, second, and third Battalions of the second King’s African Rifles Regiment; first and second Battalions of the third King’s African Rifles Regiment; and third and fourth Battalions of the fourth King’s African Rifles Regiment

- German East Africa Garrison: third battalion of the third King’s African Rifles, fifth battalion of the fourth King’s African Rifles, second battalion of the sixth King’s African Rifles, first battalion of the seventh King’s African Rifles.

- Garrison of British East Africa: first Battalion of the fifth King’s African Rifles, first Battalion of the sixth King’s African Rifles.

- King’s African Rifles Training Force: fourth Battalion first King’s African Rifles, fourth Battalion second King’s African Rifles fourth Battalion third King’s African Rifles, sixth Battalion fourth King’s African Rifles.

The King’s African Rifles’ growth included raising the number of NCOs and white officers and bringing unit strengths up to par with Indian and British Army Imperial Service units. Due to a scarcity of Swahili-competent whites, increasing the cadres was difficult, since several white settlers had already created segregated organizations such as the East African Regiment, the East African Mounted Rifles, the Zanzibar Volunteer Defense Force, and the Uganda Volunteer Rifles.

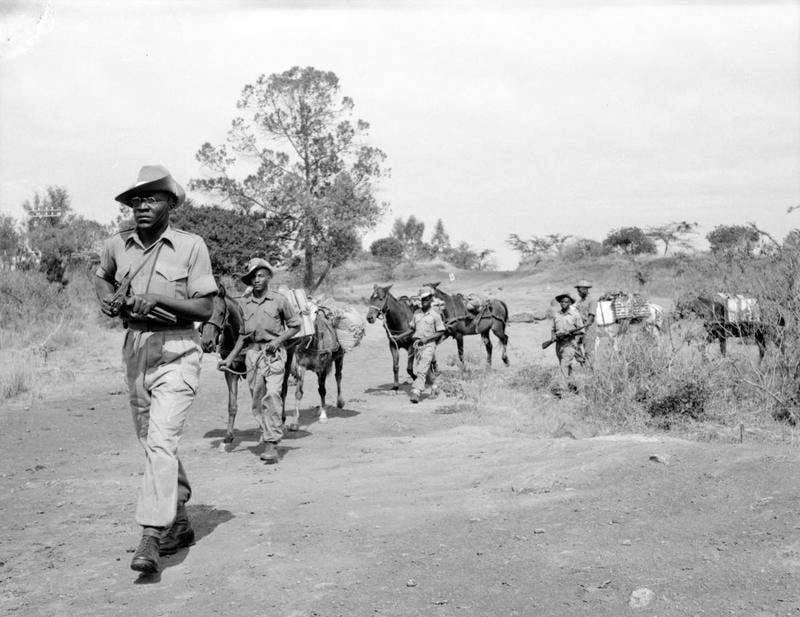

In German East Africa, the regiment faced Paul Erich von Lettow-Vorbeck, the German commander, and his soldiers during the East African Campaign. Over 400,000 Carrier Corps porters provided transportation and assistance into the interior.

The King’s African Rifles had 1,193 British officers, 30,658 Africans, and 1,497 British NCOs (a total of 33,348 men) in twenty-two battalions at the conclusion of the Great War, including two battalions consisting of former German askaris, as mentioned above. Peter Abbot writes in his book Armies in East Africa 1914–18 that the British deployed King’s African Rifles battalions made up of former prisoners of war as garrison soldiers to prevent any allegiance conflicts. However, from February 1917 to October 1917, one battalion was actively pursuing a force led by Hauptman Wintgens.

In World War I, 5,117 King’s African Rifles soldiers were killed or injured, with another 3,039 dying of sickness.

Inter-War Years

In the interwar years, the King’s African Rifles was gradually demobilized to a peacetime size of six battalions, which it maintained until the outbreak of WWII. The regiment was formed in 1938 from two brigade-sized formations known as the “Northern Brigade” and the “Southern Brigade.” Both regiments had a total strength of 60 non-commissioned officers, 94 officers, and 2,821 Africans of other ranks. These battalions provided the training core for the King’s African Rifles’ fast development after the onset of the conflict. The King’s African Rifles had grown to 1,374 non-commissioned officers, 883 officers, and 20,026 African other ranks by March 1940.

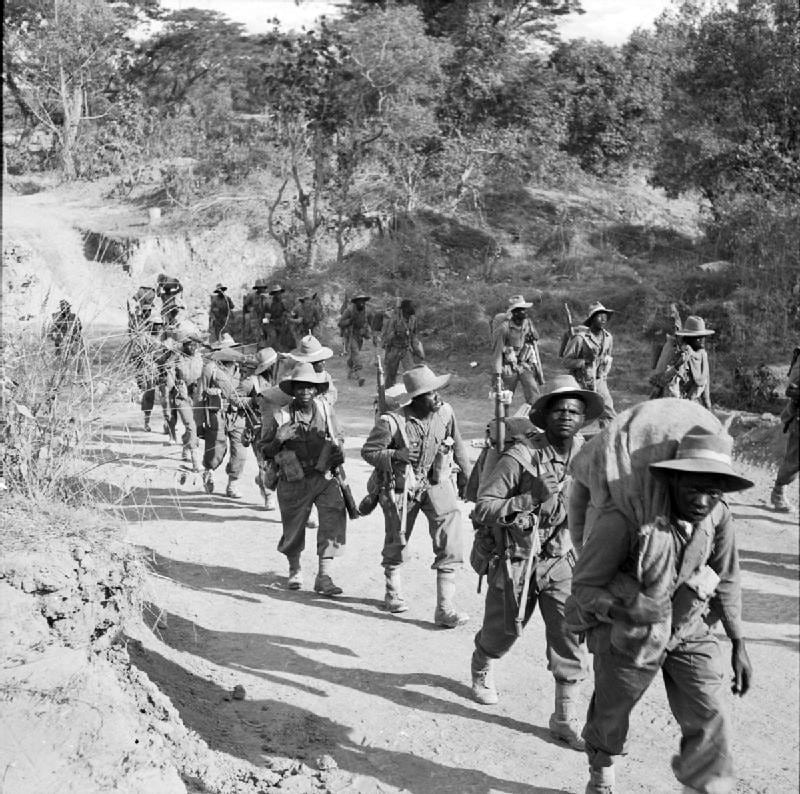

King’s African Rifles WW2 Involvement

During World War II, the King’s African Rifles participated in a number of campaigns. During the East African Campaign, it battled the Italians occupying Italian East Africa, In the Madagascar Battle, it fought the Vichy French, and in Burma, they fought against the Japanese in the Burma Campaign. The Somaliland units were extensively involved in fighting off the Italian invasion of the colony in August 1940, however, they were forced to evacuate and retreat after being defeated at the Battle of Tug Argan between August 11 and 15.

The first East African Infantry Brigade and the second East African Infantry Brigade were the original names of the King’s African Rifles. The first brigade was in charge of coastal defense, while the second was in charge of interior defense. Two more East African brigades, the third East African Infantry Brigade and the sixth East African Infantry Brigade were organized in July 1940. A Northern Frontier District Division and a coastal division were originally proposed, but the eleventh and twelfth African Divisions were built instead.

East African, South African, Nigeria, and Ghanaian forces made up the two divisions. The Royal West African Frontier Force provided the Nigerian and Ghanaian troops. Brigades from Nigeria and the Gold Coast (present Ghana) were sent to Kenya as part of a war contingency plan. The eleventh African Division was created by two King’s African Rifles brigades, a Nigerian unit, and a number of South Africans. The Ghanaian brigade replaced the Nigerian brigade in the formation of the twelfth African Division.

Sergeant Nigel Gray Leakey was given the Victoria Cross award during the East African war in 1941.

The eleventh African Division and the twelfth African Division were both abolished in November 1941 and April 1943, respectively. The eleventh Division (East Africa) was established in 1943 and battled in Burma. Two autonomous infantry brigades from East Africa were also dispatched to India for duty in Burma, India. The 22nd Infantry Brigade (East Africa) participated in the Arakan under the leadership of the XV Indian Corps, whilst the 28th Infantry Brigade (East Africa) fought under the IV Corps, and both played a critical role in the Irrawaddy River crossing.

The regiment had established 43 battalions (two of which were in British Somaliland), 9 autonomous garrison companies, one artillery unit, one armored car regiment, and transport, signal, and engineer sections before the conclusion of the war.

Post-World War II

In the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya, the King’s African Rifles’ regiment was heavily involved in operations. The 7th Battalion (Kenya) was reorganized in 1952, and in 1956, it was renamed the 11th Battalion (Kenya). The reserve unit second/third Battalion was established during the military phase of the Kenyan emergency and was on the verge of being disbanded by 1957. In connection with the 1952 Chuka massacre, a company of the army was accused of war crimes.

The first, second, and third battalions were severely involved in combating Communist insurgents during the Malayan Emergency, losing 23 men in the process.

In 1957, the regiment was renamed the East African Land Forces. HM Queen Elizabeth II was the last Colonel-in-Chief of the King’s African Rifles.

The regiment began to disband as the several territories from where the King’s African Rifles was formed gained independence:

- Malawi rifles, First Battalion – 1st Battalion

- Northern Rhodesia (later Zambia regiment), second Battalion – 2nd Battalion

- Kenya rifles, Third battalion – 3rd Battalion

- Uganda rifles (continued to form the Ugandan army), 1st Battalion – 4th Battalion

- Kenya rifles, Fifth Battalion – 5th Battalion

- Tanganyika rifles, 1st Battalion – 6th Battalion

- Kenya rifles, 11th Battalion – 11th Battalion

- Tanganyika Rifles, 2nd Battalion—26th Battalion

The level to which King’s African Rifles traditions affect the present national forces of former East African colonies differs. A revolt in Tanzania in 1964 prompted a deliberate shift away from the British military paradigm. The designation of Kenya Rifles, on the other hand, lives on in Kenya, and the several campaigns of the two world wars in which the King’s African Rifles stood out are still remembered. A unit of the King’s African Rifles was stationed on the island of Mauritius until 1960. The newly constituted Special Mobile Force (SMF) and Police Riot Unit (PRU) and Special Mobile Forces (SMF) progressively took its position.

The Kenya and Malawi Rifles are the only two regiments that still exist.

Honors in Battle

Colors were not usually carried by rifle regiments; hence the battalions of the regiment did not get them until 1924. Many of the regiment’s combat honors were embroidered on the colors. In the 1950s, the previous colors were replaced

- Ashanti 1900 (awarded in 1908 for The Central Africa Regiment’s services in British Somaliland 1901 – 1904).

- The Great War (seven battalions): Nyangao, Narungombe and Kilimanjaro, East Africa, 1914–1918.

- Word War II: Kulkaber, Ambazzo, Gondar, Omo, Colitoritus, Fike, Awash, Beles Gugani, Juba, Soroppa, Moyale, Afodu, Todenyang-Namuraputh, Abyssinia 1940–1941, British Somaliland 1940: Tug Argan, Middle East 1942, Madagascar, Letse, Seikpyu, Kalewa, Mawlaik, Burma 1944 – 1945, Tangup, Arakan Beaches.

Commanders’ List

Inspectors-General

- Brigadier-General William Henry Manning served from October 1901 until 1907.

- Gough, John

- Colonel George Thesiger, 1909 to 1913

Servicemen to Note

- In 1946, Idi Amin, the future dictator of Uganda, joined the KAR.

- Roald Dahl, discusses it in his book Going Solo.

- Art dealer Robert Fraser

- Sir George Giffard, A general.

- Major-General Freddie de Guingand, CB, KBE, DSO, was seconded to KAR from 1926 until 1931. Served as Sir Bernard Montgomery’s Chief of Staff during WWII operations from Egypt to Northern Europe.

- As an accountant, David Gordon Hines went on to become Uganda’s Commissioner for Cooperative Farming.

- In the Mau Mau revolt, Waruhiu Itote was known as “General China.”

- VC Nigel Gray Leakey

- J. Marshall, an eighteenth-century historian of the British Empire

- Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen is a general in the United States Army.

- “Mad Mitch” – Lieutenant-Colonel Colin Mitchell.

- Tales from the King’s African Rifles author John Nunneley

- Barack Obama’s grandfather, Hussein Onyango Obama

- Uganda Army Commander Shaban Opolot

- Tracy Philipps is an adventurer, colonial administrator, and environmentalist.

- 1st Battalion KAR Captain Henry Walker Alexander Walker

- VC Eric Wilson

- Seymour, John (author)

- Malawi historian George Shepperson

- Tanzanian military officer David Musuguri

- Tanzanian military officer John Butler Walden

Other Things to Know About the King’s African Rifles

- King’s African Rifles Association – http://www.kingsafricanriflesassociation.co.uk/

- King’s African Rifles marching song – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TpOymRYn1AI

- King’s African Rifles museum – Imperial War Museums

For more articles about Tanganyika click here!