Matengo People – History, Language, Socio-Political Setup

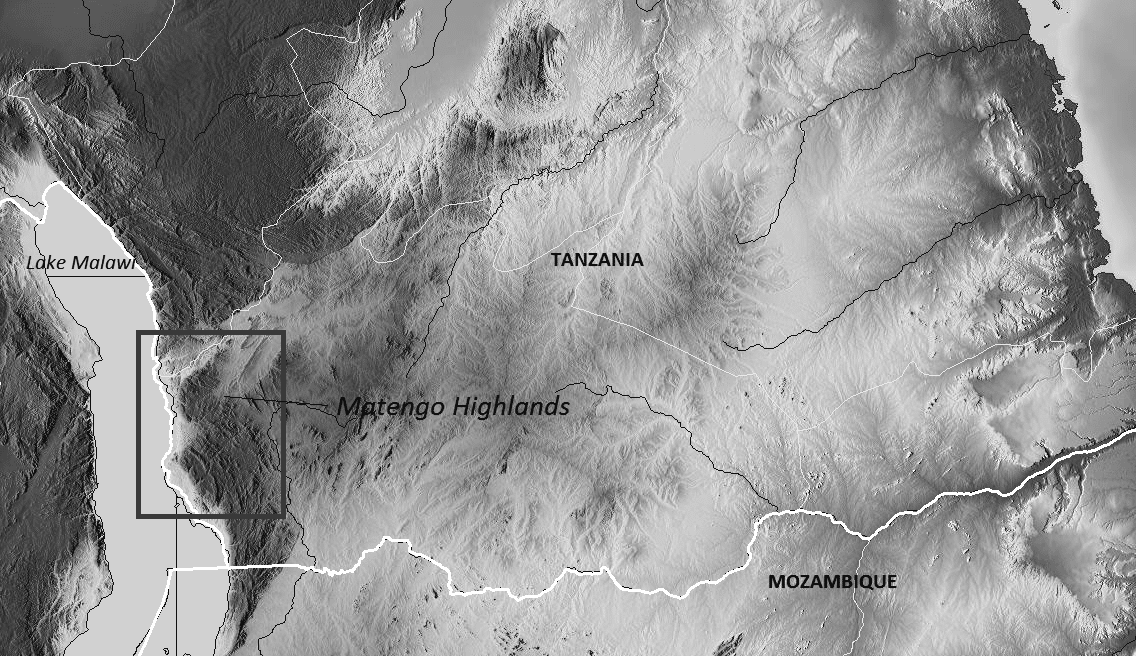

The Matengo people are a linguistic and ethnic group in southern Tanzania’s Ruvuma Region, where they are centered in Mbinga District. Matengo’s population was approximated to be 57,000 in 1957, but it was approximated to be 284,000 in 2010. Their religious beliefs are based on Christianity. Their Affinity Bloc is made up of people from Sub-Saharan Africa. Matengo is their primary language, and it is a Bantu language.

History

From the Iron Age, the Matengo is said to have resided in Matengo Highlands.

Before 1750, the Maseko Ngoni people of Malawi’s Dedza district entered the region where the Matengo lived. As a result, the Matengo people were forced to flee to the highlands near Litembo, where most of them sought refuge in caves. In the northeastern portion of the area, many residents moved into the woods. As a result of the Ngoni people’s push, the Matengo formed a power hierarchy among them, with the main chief overseeing three other local chiefs. During the colonial era, this system remained strong until just before the 1961 independence. A major increase in the population of the Matengo in the latter years of the 1960s led to food scarcity and had a direct influence on the distribution of the population, with many relocating to the eastern portion of the district and building new villages to practice farming on the land seasonally.

Demographics

Mbinga district is home to four ethnic groups: Matengo, Ngoni, Nyasa, and Manda, with the Matengo accounting for 60 percent of the population and a population density of thirty-four persons/km2 in 2000. The population density of the Matengo was found to be 120 people/km2 in the Matengo Highlands. As a consequence of the increased demand for land, people have begun to migrate from the highlands to the northeastern forests.

Setup of Socio-Political

The Matengo’s “socio-geographic units” were initially made up of a “non-hierarchical” political system that included “a collectivity of sovereign matrilineal groupings of similar status and various origins”. Each kilau (patrilineal group) represented people with a common ancestor, who had been the group’s undisputed leader (bamboo and matukulu) throughout his lifetime. As a result, the villages’ socio-political was comprised of elders and a headman. The political hierarchy of the Matengo developed into an administrative structure after the area was invaded by the Ngonis, with a senior chief, three chiefs, a senior headman, and 2 tiers of the headman in declining order of significance in the hierarchy. This structure was strengthened throughout the colonial era. Following Tanzania’s independence in 1961, the kilau (patronymic unit) is exclusively used to name family siblings. The village’s current administrative structure comprises of a “Village Chairman” as well as a complement of members who are responsible for administering the village under the supervision of the local government as well as the central government.

Language

The Matengo language is a “medium-sized language,” a descendant of the Bantu language that is widely spoken in Tanzania’s southwestern portion. Bantus are also called “woods people” (a derivation of the term “kitengo,” which means “thick woodland”). The Swahili terms, on the other hand, have affected the Matengo, especially the vocabulary. Matengo’s grammar and pronunciation have changed as a result of Swahili influence, and there has been some code-mixing. As a consequence, the Matengo language is progressively being Swahilized, and most of the younger population prefers to communicate in Swahili.

Agriculture and the Climate

The Matengo people live in Tanzania’s southern highlands, a hilly region with elevations ranging from 900m to 2000m asl. Below 1400 meters, the area is a mostly open forest called miombo, with a high Caesalpiniaceae plants concentration. The climate is normally cold, with an annual average temperature of 18 °C, and it is rather rainy, with a mean annual rainfall of roughly 1000 mm.

The Matengo’s ancient agricultural practices are known as Ngolo or Ingolo Ingolo or Ngolo. The Matengo have innovated an ingenious manner of farming on steep slopes during the past 100 years, constructing pits on ridges found on steep slopes to minimize soil erosion and produce sustained productive soils. The pits’ purpose is to stop heavy rain from carrying away the soils on steep slopes by functioning as sedimentation tanks, trapping green grasses and giving nutrients for the season to follow. Under this unique style of agriculture called “Matengo Pit Cultivation,” the major crops they plant are coffee and staple food crops. This farming activity normally begins in March after the wet season. Their strategy entails a two-year one-cycle rotation of maize, peas, and beans, with a short-fallow interval in between. For example, in Matengo maize cultivation, a farmer would cut 5 cm furrows on the ridges in November and plant the seeds, then begin weeding in December. In July, the maize is harvested, and the field is left fallow until the subsequent March, allowing the soils to recuperate. Cassava is frequently planted in May or April if bean planting is delayed. Often, the farms contain solely cassava, which the Matengo refer to as “kibagu” and is typically farmed for 2 to 3 years. Cassava, like sweet potato, is often planted to supplement food supplies amid poor harvests. Maize, beans, and, to a lesser degree, cassava are often grown together in fields. Beans, unlike maize, are harvested early in the season, around March. Onions, cabbage, tomato, and Chinese cabbage are also reported to be grown by some.

The Matengo harvest coffee while practicing sedentary agriculture in the country’s hilly highlands. It was brought to Mbinga District around the 1920s by ex-Senior ruler Yohani Chrisostomus Kayuni’s son to allow the Matengo to pay the colonial administration’s poll tax demand. The cold and rainy climatic circumstances enabled the area to achieve coffee sustainability, resulting in the district being a key coffee-producing area in Tanzania. This also improved people’s economic circumstances, with other families becoming quite wealthy. Previously, the Mbinga Cooperation Union (MBICU) was in charge of helping the Matengo farmers’ coffee sector. They filed for bankruptcy in 1993, after economic deregulation, since they were outcompeted by private farmers.

Social Customs

The Matengo civilization is polygamous and has a patrilineal system. Each family’s property holding is often a short ridge of the hill area next to streams for irrigation water. The land they farm is known as “ntumbo.” Married women frequently rent ntumbo land from their fathers-in-law and use it to produce staple foods like beans and maize. In order to boost their income, they also keep pigs and cattle. The males, on the other hand, plant coffee only as a cash crop to assure economic stability.

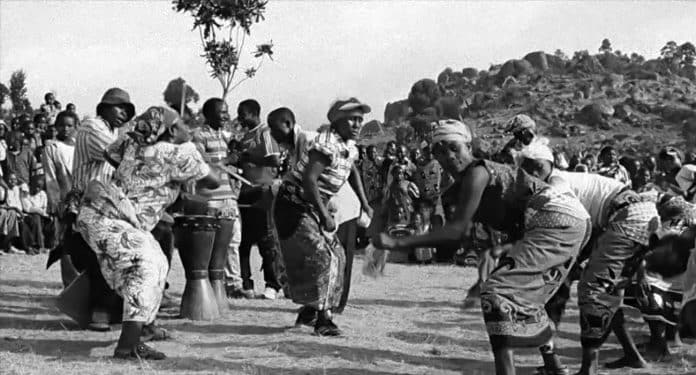

The musical changes witnessed here are a reflection of political and economic shifts, as well as the highland dancers’ gendered decisions.

Matengos live in a single-roomed jiko (home) tenements that serve as their dining room, kitchen, and favorite gathering spot for visitors. Ugali, a thick maize porridge, is their major daily meal; meat or fish or may be added to ugali.

Folklore – Matengo Folktales

The Matengo have a rich folklore, and traditional stories are handed down orally to the future generation. Catholic missionaries recorded the Matengo people’s traditional stories, and Father Johannes P. Häfliger became the first to publish a collection of them. The Matengo language does not have a script or a standardized sound system. As a result, all the stories are spoken orally and then translated to English. Families or animals are usually involved. “Hare and the Drought,” “How the Hare Assisted Civet,” and “What the Hare Did To the Lion and the Hyena,” “Hare, Civet, and Antelope,” “The Tale of Two Women,” “The “The tale of a Nephew and his Uncle” the “The story of Nokamboka,” “Katigija,” “The Hawk and the Crow,” and “The Monster in the Rice Field” are among the most well-known Matengo folklore. The “How the Hare assisted Civet” folk tale talks about a naïve African cat, his companion Lion, who tricks and hoodwinks him, and the Hare, a con who outwits the Lion and exacts justice for Civet. These folktales have been collected in a book by Joseph Mbele, which has been translated to English.

For more articles on the Tanzania Tribes click here!