Cassava Production in Tanzania – History, Storage, Processing, Marketing and More

A Story of Cassava Production in Tanzania from One of the Farmers

Mahomed Rajabu is a cassava farmer who lives in Tongwe village, which is approximately 50km to the southwest of Tanga City on the Indian Ocean coast of Tanzania. Cassava has changed the lives of Mr Rajabu and his family. He currently produces enough crops to cater for his domestic needs and sells the remaining crop as cassava flour.

Mr Rajabu is a member of the Tongwe Farmers Group. The group owns a farmer-run cassava processing centre in Tongwe. The centre contains both power and manually operated graters and chippers, as well as machinery for squeezing water from grated cassava. Cassava chips and grated cassava mash are dried and then milled into flour for sale.

Before Mr Rajabu started farming cassava, he faced difficulty supporting his family due to poor harvests as a result of low rainfall. However, since he began growing the crop, the rising demand assures him of enough income.

As a result of increasing production, Tongwe Farmers Group signed an agreement with a local supermarket chain allowing it to sell cassava processed by its members at market prices.

Cassava has provided Mr Rajabu with economic security, prompting him to start other businesses. He bought a shop in Tongwe using the profits he obtained from cassava sales, investing a total of 3,000,000 Tanzanian shillings ($1,800), this store supplies basic commodities such as sugar, soap, plastic utensils, cooking oil and salt.

Background of Cassava Production in Tanzania

The native origin of cassava is tropical America; it was introduced to the African continent around the mid-1500s and reached East Africa in the 1700s. It is currently the staple food in most regions of Africa. Other than being a staple food, cassava starch and cassava and its by-products are utilized in a wide range of products: glues, confectioneries, plywood, paper, pharmaceutical drugs and textiles. Cassava pellets and chips are used in alcohol production and as animal feed.

Cassava serves as a staple food to over five hundred million people in sub-Saharan Africa. It is a crucial food security crop in addition to generating income for poor households in several countries. Over 18 million hectares of cassava are grown worldwide, with two-thirds of them produced in Africa. Approximately 93% of the cassava produced in Africa is consumed as food.

Cassava production in Tanzania has made the country the fourth-leading producer of cassava in Africa, producing over seven tones of cassava, with 84% of it consumed as food. Cassava is a major food crop in the lake zone and the coastal regions of Tanzania. The crop is cultivated throughout the country, but the major growing regions are the Lake Victoria zone (Mara, Mwanza, Shinyanga and Kagera regions), the Southern Zone (Tunduru district in Ruvuma and Lindi and Mtwara regions), the Eastern Zone (Tanga, Morogoro, Dar es Salaam and Coast.) and Zanzibar ( Unguja islands and Pemba.)

Storage

Famers usually store fresh cassava roots underground and harvest them on demand. Sacks can be used to store the harvested roots only on a short term basis, as deterioration begins two days post-harvest.

After being processed at home, dried cassava chips are usually stored using traditional methods such as sacks, on the house floor, attic or in large woven round baskets (Vihenge). Storing the cassava chips on raised platforms above the cooking area or in the attic smokes them hence preserving them, Chips may be stores for up to three months before insects start damaging them and up to a year when smoked. Dried cassava chips are more marketable and fetch higher returns because they are more easily transported by the trader. High-quality cassava flour can be stored for up to a year.

Processing

Post-harvest is an important aspect in cassava production in Tanzania. Cassava roots are transported to processing regions via small tractors, carrying the roots or by bicycles. Some of the roots are processed on the farm, at home or in small and large processing plants.

Processing cassava after harvesting vastly improves its commercial value. HQCF possesses a high potential as a commercial commodity. Cassava starch, cassava flour and cassava chips can be used in place of imported wheat as an ingredient in adhesives and as animal feed. (Brazil includes 2 per cent of cassava flour in wheat flour bread, Nigeria has also recently made it mandatory to incorporate 10 per cent cassava flour in bread). Furthermore, countries that produce cassava import several starch-based commodities that can be locally produced from cassava.

The main products processed from cassava are milled products such as bread, biscuits, confectioneries and flour; animal feed for pigs, cows and poultry; beer and other beverages, snacks and sweets. Cassava starch is utilized in various industrial products such as paper, textiles, glue, pharmaceuticals and paints. When fermented, cassava starch is also used to produce ethanol for biofuel.

Effective processing, for instance, grating and soaking, eliminate toxins that naturally occur in the roots, decrease the product’s weight for easier transport, reduce losses incurred after harvests due to root breakage, and improves the product’s shelf life.

Cassava roots have a toxic compound called hydrogen cyanide that is harmful to humans. The amount of this substance found in bitter cassava is about fifty times that found in sweet cassava. Cyanide content in both roots is vastly reduced during processing rendering them safe for consumption by humans.

Making High-Quality Cassava Flour (HQCF)

The 9-step process of cassava production in Tanzania used in producing HQCF from raw cassava roots is outlined below.

Step 1:Selecting roots

Use mature, healthy, firm, freshly harvested unbruised cassava roots. In white varieties, the root’s flesh should be white with minimal fibrous roots and no cracks.

Step 2-peeling

The roots are peeled using a sharp knife to remove the stalk, fibrous roots and woody tips. The cassava peels can be dried and used in making compost or as animal feed. The graters and peeler should be cleaned before and after use.

Step 3:washing

Peeled cassava roots are cleaned twice with clean water to remove sand, soil, leaves, dirt and any other impurity.

Step 4: Grating

A stainless or mild steel grater is used to grate roots to fine mash.

Step 5: pressing

The fine mesh is packed in bags such as jute or sisal sacks that allow excess water to escape. The sack is pressed to eliminate any excess water using a hydraulic jack, screw press or another process until the cassava becomes crumbly.

Step 6: Drying

The cassava mash is pressed thinly on a thin plastic black sheet spread in the sun on a gentle slope. Typically, the sheet should be raised. The mash is dried till the level of moisture drops to below 12 per cent. The chips crack when handled at this moisture level. The netting is covered to protect from birds and flies. Stoves, hot-air and solar driers are more costly but offer higher quality and a more reliable drying process.

Step 7:miling

The dried cassava mash is milled with a hammer mill (kinu mill/ village posho) to turn it into flour.

Step 8: Sifting

The milled flour is sifted using a sieve to eliminate lumps and fibrous materials. This is crucial to obtaining free-flowing high-quality flour, with good particle size and free of fibre.

Step 9: Packaging and Storing

Sifted Flour is packed in black moisture-proof airtight plastic bags. The bag is sealed with a burning candle and expiry and manufacture dates labelled (After a year). The bags are packed in cartons to insulate them from light. The cartons are stored in a cool, well-ventilated, and dry place. The packaged flour is viable for approximately a year.

An alternative way of producing cassava flour is by incorporation of a fermentation stage resulting in the production of a mildly sour product called gari in West Africa. The fermentation can either occur when the water is being removed or by soaking cut or whole roots for 3-5 days until they are fermented. The fermentation process should be keenly monitored to ensure all the toxic cyanide gas is released from the roots and the texture and flavor of the product are acceptable.

Processing Roots into Cassava Chips

The initial three stages of producing cassava chips are similar to the production of cassava flour ( roots selection, peeling and washing). However, instead of the roots being grated into fine mash, they are chipped using a powered or a mechanical chipper.

The chips are then dried using in the sun or using a mechanical dryer on raised platforms. Cassava chips are frequently infested by insects while drying, making it necessary to minimize the drying period. Smaller chips dry faster.

Cassava chips are dried until they can easily break without crumbling. The chips are packaged after drying.

Making Cassava Starch

Traditionally, cassava starch is used to produce foods such as bread, biscuits, and puddings. It is also an ingredient in the production of non-food items including paper, textiles and pharmaceuticals.

The initial stages of production involve peeling, washing and the grating of the roots. Three times as much clean water as the cassava is mixed with the cassava in a bucket and left to rest for 35-40 minutes.

The mixture is then poured through a clean cloth and left to sit for at least an hour. The water is then poured off and the settled pieces at the bottom of the bucket are broken into smaller pieces. The pieces are then sun-dried or dried artificially for at least six hours. The cassava is then milled to produce starch.

Processing Tools Involved in Cassava Production in Tanzania

Simple tools and machines can decrease the processing time, cut losses by 50 per cent and reduce processing labor by 75 per cent. Cassava products can be processed manually or using powerful chippers and graters. Grating decreases the cyanide in Bitter cassava to consumable levels. However, in the absence of graters, the roots can be soaked in water for about for days before being processed further. This allows the safe release of the cyanide gas, minimizing the health hazard. The water used for soaking the roots must be carefully disposed of by the processors.

Mechanized pressers, graters, and mills are a common sight in Nigerian, Ghanaian and Ugandan villages. However, villages in Tanzania have limited access to mills as several villages lack petroleum and electricity.

Animal Feed

Small-scale producers and processors have increased opportunities to provide higher quality cassava chips (“enhanced” makopa) to the ever-growing animal feed industry, more so for poultry feed

Other Products

Opportunities for supplying clear and traditional beer as well as cassava for the cassava-based snack industry may exist.

Waste Products of Processing

A lot of waste is accumulated during cassava processing, majorly cassava peels. The peels are mostly consumed by livestock such as goats, pigs abs and cows. The leaves and peels supplement animal feeds, rather than sole dependence on grass and other fodders. The peels are can also be utilized in making compost to restore the fertility of the soil.

Processing Challenges Involved in Cassava Production in Tanzania

Availability of clean water: Clean water is required in washing the roots and making starch. Accessing clean water is often a challenge in Tanzania due to inadequate water infrastructure. Processors obtain water from rivers and wells as well as piped water, rainwater and borehole although some of these water sources dry up during the dry season. The quality of cassava produced without clean water is low.

Inadequate harvests: Large cassava processors face difficulty in obtaining a continuous and sufficient supply of cassava roots due to the uncertainty of harvest in Tanzania. Whilst cassava can be harvested all year, the best time for harvesting is during the dry season which is convenient for sun drying. Therefore, cassava is usually sun-dried in the dry seasons between June and October and in January and February. This poses a problem for processors to operate their factories continuously or to make expansion arrangements.

Shortage of processing machines: Several reasons contribute to the scarcity of processing machines in Tanzania: processors have no motivation to acquire them due to the low production volumes of cassava; a limited number of manufacturers of the processing equipment in the country; high-interest rates associated with financing the machinery investment as well as lack of electricity in several rural areas of Tanzania.

Gender Issues Involved with Cassava Production in Tanzania

Cassava production in Tanzania is neither a women’s or men’s agricultural activity as both sexes are involved, even though they often specialize in different stages of production. Men normally clear land, plough and plant while women weed, harvest, transport, store and process the crop.

However, men are attracted to marketing and processing due to the potential earnings. Traditionally, men are heads of their households and make the decision regarding the sale of cassava products and oversee the spending of the generated income. Smaller sales are overseen by women, who majorly use the money for domestic necessities such as matches, salt, school supplies and soap.

Marketing

The majority of farmers who are involved with cassava production in Tanzania sell their products in addition to consuming them at home. According to a survey of 600 households done in 2013 by Farm Radio International in Mtwara and Tanga in Tanzania, over 90 per cent of female farmers and male farmers of cassava grow cassava both for sale and for home consumption.

The major forms of processed cassava in the country are cassava flour and chips, although the majority of Tanzanian farmers sell as raw cassava tubers, which reduces their potential earnings. In rural regions, cassava is cultivated as a security food and as a staple food. In urban regions, Chips and HQCF compete with food grains.

Cassava farmers typically sell their cassava individually rather than via groups, which limits their bargaining power. Groups in Mtwara and Tanga suggests that this is mainly due to the desire to fulfil immediate needs such as medical services, food, and school supplies. According to farmers, although they get better prices as a group, disbursement of payments takes a long period to be completed.

Farmers of both genders point out that vendors and middlemen and women exploit them by buying their cassava at extremely low prices. In the focus groups in Tanga, farmers reported that the harvesting, grading, sorting and packing is organized by vendors. Due to the absence of weighing scales, vendors stacked bags up to one and a half times the usual size, mainly because of the lack of bargaining power by the farmers.

Farmers are usually under-informed about local markets. The majority of them wait for middle persons to visit their farms, lowering the farm gate price. Limited storage and transport facilities further complicate the marketing of cassava. Due to the bulkiness of cassava, farmers are forced to sell their crops to middle people or at local markets at low prices. Roads to regions where cassava production in Tanzania is heavily practiced are generally poor. Most farmers who are informed about the market receive information from other farmers and vendors. The survey done by Farm Radio International established that no one got market information via the radio due to few farming programs with none focusing on cassava.

Opportunities for Processed Cassava

There are possibilities to market HQCF to bakeries for it to be included in wheat flour. It is cheaper in comparison to wheat flour which is exclusively imported. Many bakeries in Mtwara are presently including 10% HQCF to their wheat flour, this is contributed by the high transportation cost of wheat flour from the port of Dar Es Salaam. The national standard for wheat bread in Tanzania permits the inclusion of a maximum of 30 per cent of other flours.

Several other opportunities exist for cassava flour, including bulk supply of HQCF to biscuit manufactures; supply of mixed HCQF and wheat flours to millers for home baking mandazis, chapattis, cakes and doughnuts; as well as supplying blended HQCF and maize flour to millers for preparing ugali.

Marketing Challenges Related to Cassava Production in Tanzania

Farmers who aspire to market and process value-added cassava products encounter a variety of hurdles. The majority of cassava farmers from both genders who took part in the survey identified the major marketing challenges like lack of a guaranteed market and lack of information on the current market rates. Some of the other marketing setbacks experienced in Tanzania are discussed below. (Most of the other cassava-growing countries encounter some of these challenges too.)

Narrow sales channels: Facilities that process flour in Tanzania experience a range of sales-related challenges, such as the absence of distribution channels for their commodities, lack of wholesalers and distributors and shortage of sales representatives.

Poor transportation infrastructure: Road conditions make distribution and transport of cassava products challenging. The challenges and costs in distribution and transportation are so bad that large markets such as Dar Es Salaam find it more economical to import products rather than buy them locally.

Low prices: Farmers involved with cassava production in Tanzania especially in rural areas are under-informed about the market prices, leading them to sell their crops at extremely low prices. Mobile phones have improved the access to market prices, though a majority of farmers are not organized well enough to negotiate fair prices with processors and vendors. The confinement of sales and harvests to dry season weakens the bargaining power of farmers.

Inadequate financing: Investment in processing equipment and development of new products is capital intensive. However, private banks are reluctant to finance cassava related businesses due to the negative image of cassava in the country. Additionally, high-interest rates largely limit the income of the

processor.

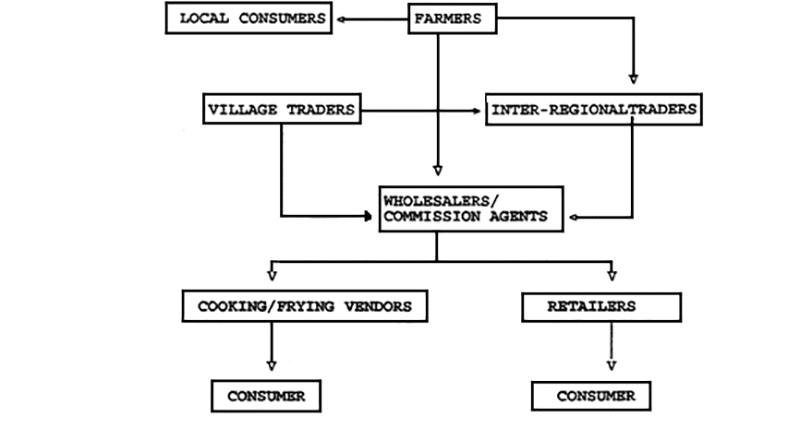

According to figure above, which shows the marketing system for fresh cassava roots in Dar Es Salaam, fresh cassava is directly sold to local consumers at local markets, village traders or to inter-regional traders after it is harvested. Thereafter, the fresh produce is transported by the inter-regional traders using trucks for wholesale in urban Dar Es Salaam markets. Commissioned Agents and wholesalers sell the fresh cassava on behalf of farmers and inter-regional traders to frying and cooking vendors or to small scale retailers who then sell them to urban consumers.

The marketing system is identical in Tanzanian rural villages, where farmers sell dried chips or fresh roots to consumers and local market traders, who consequently transport them to cities and big towns for sale to market vendors and retailers.

For more Food Crops in Tanzania articles click here!