Julius Nyerere Ujamaa – Ideologies, Practices, Infrastructure, Villages and More

What Does Ujamaa Mean?

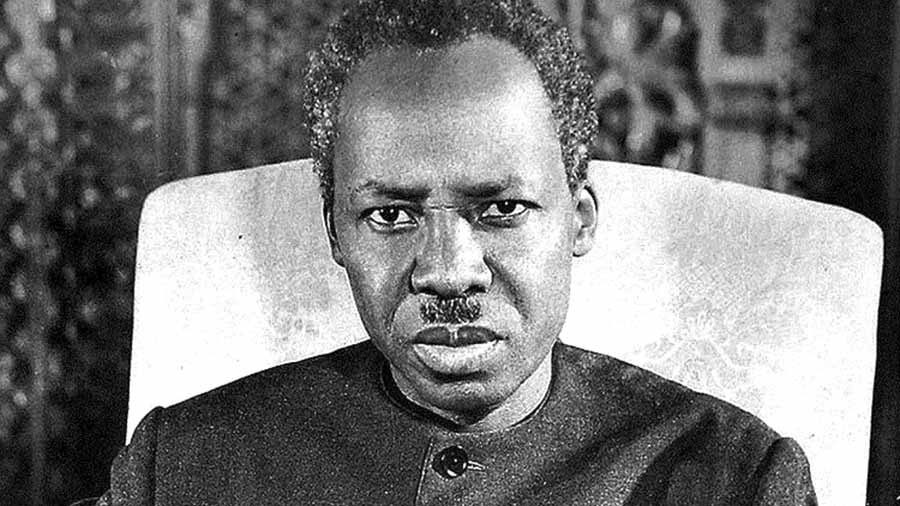

One cannot talk or define Ujamaa without mentioning the name Julius Nyerere first. Ujamaa (familyhood) was a socialist belief that Julius Nyerere used as the basis of his economic and social development policies in Tanzania following independence in 1961.

Meaning of Ujamaa and the proper Ujamaa definition – Ujamaa broadly means cooperative economics, in a way of the locals working in cooperation to provide the living essentials or to maintain and build their own shops, stores, and other businesses as well as profiting together from the businesses. Julius Nyerere and a number of other Pan Africanists during his era definitely showed the real Ujamaa meaning through their leadership styles. In simplicity, Ujamaa the basis of African socialism was the popular form of politics many countries in Africa took after they got their independence from the colonialists.

That said, in simple terms Ujamaa in English language just means “socialism”. And the proper way to pronounce Ujamaa is as follows:

Oo – jaa – muh

Most people do not know how to pronounce Ujamaa because it is a word derived from a Swahili language which is way different from English and many other major international languages.

Tanzania Ujamaa Philosophy, Ideology and Practice

Tanzania President Julius Nyerere published the blueprint for his development plan in 1967 titled the Arusha Declaration. In the blueprint, Nyerere outlined the need for a model of development for Africa and this formed the foundation of Ujamaa policy. Ujamaa is a Swahili word that means brotherhood or extended family; it asserts that the community or the people are what makes a person a person. The spirit of community or others bringing family units together and fostering love, cohesion, and services.

Ujamaa in Tanzania

Ujamaa philosophy by Julius Nyerere based a national development project on Ujamaa. He translated his African socialism Ujamaa concept into a political and economic management model using various means:

- The establishment of a one-party system under the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), in an attempt to solidify the cohesion of the nation.

- The institutionalization of economic, political, and social equity by creating a central democracy; abolishing discrimination based on ascribed status; and the nationalization of the key sectors of the economy.

- Production was villagized, this collectivized all the means of local productive capacity.

- The self-reliance of Tanzania was fostered via two dimensions: cultural and economic attitudes transformation. Economically, everybody would work for themselves and the group; Culturally, Tanzanians were to learn to be independent of European powers. In Nyerere’s opinion, this meant Tanzanians had to learn to be content with whatever they could accomplish as an independent nation and they had to learn to do things themselves.

- The implementation of compulsory and free education to all citizens sensitize them to Ujamaa principles.

- The establishment of a Tanzanian identity rather than a tribal one via means like the national use of Swahili.

The approach used by Nyerere in Tanzania caught international attention and commanded worldwide respect for his constant emphasis on ethical principles as the foundation for practical policies. Tanzania made great progress under Nyerere in key sectors of social development: Infant mortality rate dropped to 110 per 1000 live births in 1985 from 138 in 1965; life expectancy at birth increased to 52 from 37 between 1960 and 1984; the enrollment to primary school increased from 25 percent of age group in 1960 (with only 16 percent of females) to 72 percent in 1985 ( 85 percent of females) despite the exponentially increasing population; the literacy rate among adults rose to 63% from 17% between 1960 and 1975, significantly higher than other African states and continued to increase. However, the Ujamaa policy reduced production, breeding doubts on the ability of the project to stimulate economic growth.

Julius Nyerere used the Preventive Detention Act, a colonial law, to suppress the opposition.

Nationalizations in 1967 made the government the biggest employer in the country. Purchasing power decreased, and as per researchers of the World Bank, bureaucracy and high taxes led to a situation where businessmen opted for bribery, evasion, and corruption. A policy of mandatory villagization was implemented in 1973 under Operation Vijiji to encourage collective farming.

The Political Infrastructure in Independent Tanzania

The political infrastructure in Tanzania created to post the 1961 independence declaration was a vital response to colonialistic values. Tanzania was retained by Britain as a colonial state in world war I following the division of borders in East Africa. The state was established as Tanganyika Territory under British colonialism. In 1960, several of the local representative leadership unions started to take responsibility for the administrative requirements of the colony. The unions were formed in smaller native villages to give limited representation during the regime of the colonialists. These forms of localized governmental power enhanced the attendance of village representation. As a matter of fact, attendance and village representation at meetings held every month rose to 75 percent during this period. The rise in village participation in the infrastructure of the government took place simultaneously with the fall of the British authoritarian rule.

However, a rigid divide remained between the agents of power and peasantry. The farming population harbored justifiable mistrust because previous agricultural projects had ended in the exploitation of farmers. The Tanganyika Agricultural Corporation Schemes (TAC) acted as a project to change the pre-industrialized crop grower into an efficient systematic farmer who took part in the bigger national economy. The program was rejected by the Tanzanian peasantry as it was extremely paternalistic.

The sovereign Tanzania state was formed on 9 December 1961 and required a new political order following independence from the colonial British. During the collapse of the colonial regime, Julius Nyerere led the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) which was mostly constituted by a peasantry population. TANU managed to form a political structure that was village-organized hence allowing the localization of political representation. This enabled the party support of TANU to grow from 100,000 to 0ver a million in five years.

TANU successfully integrated various agricultural and labor unions onto their party hence ensuring the representation of the working population into the soon independent state. The leaders of the party would keep in touch with the native village elders by making trips “safaris” during which they discussed issues that were specific to the community. Individuals were elected to be representatives of the districts as soon as the borders were formulated. According to Gerrit Huizer, the elected officials were referred to as “ Cell Boundary Commissions”. The Cell leader was tasked to represent the issues of the district or village to the superior political body as well as to explain to the villagers the legislation that TANU had formed.

In 1967, President Julius Nyerere introduced an ideological sense of economic independence to counter the capitalist model that the British had imposed during their colonialist reign. Nyerere believed that instead of exporting the majority of the countries products, Tanzania could be self-sufficient by competing in the market themselves without the involvement of global trade. This was an important step for the country’s view towards the global market after gaining its independence.

Arusha Declaration

Implementation and Codification of Ujamaa

The Arusha Declaration was formed to codify the ideologies and projections of Ujamaa. This document enabled TANU to establish a countrywide consensus for the doctrines of a socialist party which were based on the principles of community and brotherhood. This declaration acted as the Party’s constitution and outlines the infrastructure of a socialist state. It detailed a progressive nation that valued individual human rights, free from a dictatorial reign. The first statement starts:

Whereas TANU believes:

- That everybody is equal;

- That everyone has a right to respect and dignity;

- That each citizen is an important part of the state and has a right to participate equally in Government at a national, regional, and local level;

- That all citizens have a right to freedom of movement, expression, association, and religious belief within the context of law;

- That each person has a right to receive protection of his property and life from the society in accordance to the law;

- That each citizen has a right to receive a fair return for their labor;

- That the country’s natural resources are possessed jointly by all citizens in trust of their descendants;

- That the state must effectively control the main means of production so as to ensure economic justice;

- That it is the state’s responsibility to actively intervene in the Nation’s economic life to ensure the wellbeing of all citizens and to the exploitation of people by others or groups, as well as to prevent wealth accumulation to the extent that is incongruent with a classless society.

The 2nd part of the Arusha Declaration scrutinizes the role of the ideologies and socialist practices of TANU. The main components of this part were “ non-existence of exploitation, Main Production Means to be Controlled by Majority Producers the Workers and Peasants, Socialism, Democracy as an ideology.”. TANU strongly believed that it was crucial that although the means of production will be under complete control of the government, the government should comprise the peasantry and working class. Moreover, TANU considered accomplishing socialism successfully without representative democracy impossible.

Ujamaa Policy in Tanzania – The Ideology of Self-Reliance and the Five Year Plan

TANU believed that capitalist markets were exploitative in nature and detrimental to the eradication of poverty. For Julius Nyerere, the country needed to form a self-sufficient economy that could hold its own against exploitative capitalist global markets. The ideology of Ujamaa was deeply based on the image of a self-sufficient nation that justified the large government expenditure to promote production.

This expansive government expenditure was introduced and further simplified in the Arusha Declaration’s two 5-year plans. Under these plans, an increase in industrial and agricultural production was promised as well as development yields specifically in rural areas. To solve this plan, Ujamaa villages were created. Ujamaa ideology heavily focused on the practices of brotherhood and communal living.

Although it was imperative for Tanzania to become an independent economy, local Ujamaa practices promoted reliance on communities. According to Ujamaa, the community was the most vital part of the society, the individual was secondary. Moreover, ujamaa encouraged the significance of communal living and a shift in economic practices in respect to agricultural development that is in line with Ujamaa ideology. Not only was ujamaa a local social project, but also prove to the international community that African socialism was achievable and could succeed in the creation of an independent community.

Ujamaa Villages in Tanzania – Ujamaa Villagization and Rural Development in Tanzania

Ujamaa ideology as highlighted in TANU’s Arusha declaration had massive effects on the structural development of the first 5-year plan. This economic and social experiment commenced in Ruvuma, Southern Songea. The Ujamaa development scheme kicked off in Litowa village.

Even though the first experiment that was done in Litowa failed because of the absence of agricultural continuity, TANU gave it another try after one year and was able to successfully create elected representation bodies and cooperatives. As a matter of fact, President Nyerere declared Litowa village an example of the ujamaa approach when he visited in 1965. As the population of Litowa increased, efforts were made to institutionalize education practices to benefit the community’s development immediately. This enabled the education of individuals to particularly have an immediate role in the communal Ujamaa living instead of undergoing the conventional foundational education approach. Construction and agricultural practices were mainly included in the curriculum of primary education in Litowa.

Litowa was an ideal example of the meaning of the ideology of Ujamaa: community engagement in civil service, communal farming, the spread of the practices of production, and the modernization of the technical skills of development (e.g construction). As the ideas of Ujamaa were promoted by Litowa, the practices of communal living and cooperatives spread. People would abandon their jobs to relocate to Ujamaa villages so as to live communally.

Litowa was an instance of success that led to mass movements in this region of the country. John Shaw, an anthropologist, argues that “ as per Nyerere, more than 7 million were moved between September 1973 and June 1975, a further four million were relocated to new settlements between June 1975 and the end of 1976. These massive relocations to Ujamaa villages proved that TANU’s and Nyerere’s ideology could be translated into a social reality.

What is Ujamaa Village Structure?

Ujamaa villages were constructed in specific ways to promote economic and community self-sufficiency. The villages were designed with homes centered in rows with schools and town halls as the center complexes. The villages were surrounded by bigger communal agricultural fields. Every household was provided with about an acre of land to cultivate food crops for their domestic use. The surrounding farms were formed to be economic stimulants as production structures.

The job description and village structure varied between the settlements depending on the village’s position in terms of development. Villages with fewer agricultural infrastructure and smaller populations had greater labor division amongst their members. Most people spent their days on the cooperatives planting and plowing staple crops. Communities with large populations faced difficulties with labor division. Agricultural yield and labor practices became problematic as the bigger villages developed. People sought less work as the ujamaa villages became more developed and they were mainly punished by being forced to work for longer hours.

TANU played a crucial purpose in helping the localized Ujamaa villages. It supplied bigger resources including access to construction material, clean water, and financing supplies. Moreover, TANU convinced people all over the country to join the communal living in the villages. This enabled the success of Ujamaa villages as professionals abandoned their jobs in other cities and join the Ujamaa villages. This generated social traction and legitimacy needed by the Ujamaa program to make its mark on the global community.

Vijiji Project

The vijiji project was the specialized Ujamaa program that aided in centralizing agricultural production in the villagization process. Project officials made sure that the villages’ population never dropped to below 250 households and that the agricultural units were subdivided into 10 cell units which enabled communal living and easy representation when presenting information to officials of TANU. The Vijiji project built cities with high modernist principles. Several scholars have studied the project. Priya Lal elaborates that the villages were made in a grid-like manner with homes that were bordered by a street leading to the city center.

Although this form of development may not seem unique, it was a big social transformation that had not been witnessed in rural Tanzania before. The Vijiji program was therefore used by the Ujamaa program in the 5-year plan to illustrate that agricultural production was achievable in a socialist community living. One of the major shortcomings of the Vijiji Project was misinformation. TANU officials often recorded preexisting villages as newly created Ujamaa Villages to exaggerate success numbers thus misdirecting resources and in turn made the creation of new villages a challenge. With the desire to exaggerate the project’s success, systemic contradictions started foiling the impacts of the program,

Ujamaa and Gender

In addition to changing several economic practices in the country, Ujamaa socialist movement also changed family dynamics in Tanzania, specifically gender roles. The Ujamaa project encouraged the notion of a nuclear family. However, the project faced continuous resistance from local people to change how gender roles were assigned in society.

The nuclear family within the budding villagization efforts directed its focus on the household instead of community relations and brotherhood, thus creating internal tensions between Ujamaa’s socialist ideas. This later caused a power struggle within the villages. However, TANU formed a government section that advocated for women’s rights and equality. This department was referred to as Umoja wa Wanawake wa Tanganyika (UWT).

According to Priya, UWT was created to solve the issues faced in integrating women into a socialist society; however, it emerged that the UWT officials were the wives of prominent TANU officials and promoted a patriarchal agenda. However, UWT made big strides towards increasing the literacy rate of Tanzanian women and create education systems, particularly for women. However, several of these academic institutions taught women how to become better wives and how their roles as wives could benefit society. For instance, Priya gives an example of a class like “Baby Care + Health and Nutrition challenges in the City” that was taught in these institutions. Although UWT later started teaching women structural development concepts, they were still being taught within the realm of home economics.

However, both genders in rural areas continued farming their individual farms to obtain income and subsistent yields for their families (especially cashew farms). Men continued to hold power while women still operated within domestic spheres. Although efforts were made to change how gender roles affected communal living, the gender binary persisted within the villages.

Ecological Effects

Several ecological effects influenced both political and economic activity during the Ujamaa project. Scholars such as John Shaw illustrate the contradictions that emerged in Ujamaa’s ecological and political undertaking. Ujamaa schemes like the Urambo scheme saw successful farming produce because of the access to African agricultural markets. This scheme was abolished by the central authority as the farmers were accumulating wealth.

The environmental consequence of the project was highly dependent on the annual rainfall in the country. The annual rainfall dramatically increases fertile soil yields in the country. Moreover, rain is crucial to the agricultural use of land. According to Shao, “ Land with only up to 20 inches…Is unsuitable for agricultural and is mainly utilized for grazing.” However, land receiving 30-40 inches of rainfall annually were utilized in cultivating staple crops and commercial crops such as cotton. During the villagization program, the population was distributed all over the country; however, the population densities of developed villages and cities were unbalanced. The land was ready for cultivation and it was upon the legal institutions to plan settlements on them.

The most significant ecological consequence in this period in the country was as a result of forced settlements by Nyerere and TANU. TANU availed more artificial ways of agricultural help whilst cracking down on yield results. Ultimately, production started decreasing and the land was underdeveloped. The crop yield and biodiversity became subpar as the land was not being used to its full potential.

Decline and End of Ujamaa Julius Nyerere Project

Ultimately, several factors led to the collapse of the development model rooted in the Ujamaa Nyerere concept. These factors included the absence of foreign direct investment, collapse in prices of export commodities (sisal and Tanzania coffee), the 1970s oil crisis, successive droughts, the start of the war with Uganda in 1978 which exhausted the valuable resources of the young nation.

Some internal factors also led to the collapse of the program. The program faced public resistance during the 1970s as the peasantry were reluctant to move to communal living from their individual farms because of a lack of financial gain from the communal farms. This prompted President Nyerere to call for the forced movement of people to the villages. Public frustration hindered the production of acceptable yields.

Another obstacle to the success of Ujamaa was the significance of self-sufficiency during a period of neoliberal economic policies. These global economic policies stifled the growth of newly independent nations such as Tanzania, even with its approach of self-propagated economic production.

In Popular Culture

The hip-hop music scene in the country was vastly influenced by key themes and ideas of Ujamaa. In the 2000s, the ideologies of Ujamaa were resurrected through hip-hop artists and rappers in the Tanzanian streets. In response to several years of corrupt government officials and politicians post-Nyerere, themes of family and unity and equality were evident in a majority of the songs. This was some form of resistance and a response to the oppression of the working class. The ideologies of cooperative economics- local people working together to provide the living essentials- are evident in the lyrics of several hip-hop artists. They encourage self-employment and self-made entities so as to promote change and raise the spirit of the youth.

Ujamaa (Cooperative economics) is also the 4th of the seven principles of the African-American celebration of Kwanzaa: “ To maintain and build our shops, stores and businesses and to jointly profit from them.

Two African American-themed dorms of undergraduates at Stanford University and Cornell University are also named Ujamaa.

Frequently Asked Questions About Ujamaa

Ujamaa Kwanzaa Principle

What Does Ujamaa Mean in Kwanzaa Celebration?

Kwanzaa Day 4 Ujamaa / Ujamaa Kwanzaa Day 4

On the 4th day of Kwanzaa celebration, the focus is centered on cooperative economics Ujamaa.

Ujamaa Kwanzaa meaning:

Kwanzaa Ujamaa cooperative economics is about building wealth as a community and distributing profit among each individual equally, this include but not limited to maintaining and growing farms, stores, shops and all other types of businesses.

Ujamaa meaning in English – A community of people who live as extended network of family, sisterhood or brotherhood and share resources and profit of all the work they do together.

Ujamaa meaning in Swahili – a community of people that live, work, and share resources and profit to a level that can be considered such as a family.

Ujamaa policy achievements and failures:

How successful was Ujamaa?

To the modern world and basing on the goals that were set to be met by the Ujamaa founders, the policy unfortunately did fail. That said, it is still gave a glimpse of potentials that societies can do things collectively for the good of everyone at a certain extentent.

Why did the Ujamaa program fail?

If the political form of Ujamaa was so good then why did Ujamaa fail in Tanzania?

There are many reasons why ujamaa failed in Tanzania, but one of the main one is was luck of funds. At the beginning of Ujamaa, the government needed massive funds to launch run its many different projects. Such projects included road building, schools and more.

Another major challenge was allocation of resources, because everything was supposed to be divided equally, you would find instances where for a example a whole family was given 1 kilo of sugar to use for a whole month. Such situations were impractical.

Ujamaa symbol

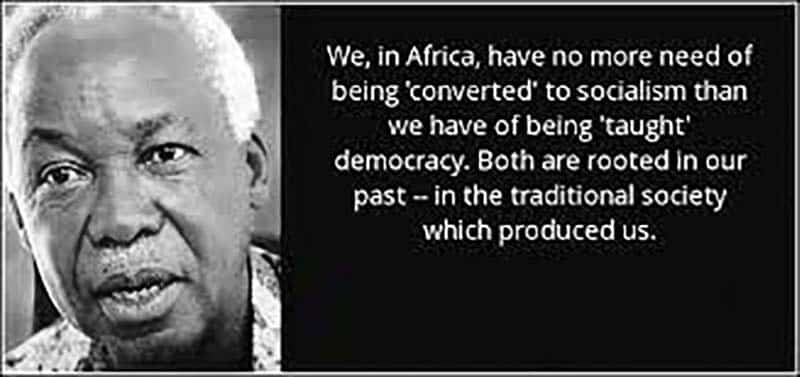

Ujamaa quotes

For more articles related to Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere, click here!