Hehe People (Wahehe Tribe) – Etymology, History, Society, Rebellion and More

The Hehe (Wahehe in Swahili language) is a linguistic and ethnic community in the Iringa area’s south center of Tanzania. The group is known for conquering a German voyage on the 17th of August 1891 at Lugalo and keeping their resistance for seven years under chief Mkwawa‘s leadership. They speak the Banty Hehe language.

A populace poll in 2006 estimated that the Hehe populace had 805,000 people. This number has increased by more than 250,000 since the 1957 poll. During the last-mentioned poll, the tribe was the eighth greatest in the country. In 2014, a further 4,023 tribe members resided in Uganda.

Etymology

The Hehe originated as the tribe’s designator during their battle cry and was initially used by their opponents. The tribe themselves only adopted it after the British and Germans constantly applied it. The Hehe was a prestigious term with its base in Hehe bloodshed, where their defeat of the Germans was declared in 1891.

History of Wahehe Iringi

A meeting of the Cabinet held on the 20th of May 1925 concluded that it was necessary to suppress the Germans’ previously maintained research establishment. The meeting stated that as per the Report of the East Africa Commission, the research opinions of the British records in Tanganyika are at risk of being criticized by the International Commission because of pressing economic situations due to the war.

In 1896, John Walter Gregory stated that there was little scientific literature about British East Africa on record. He remarked that nothing could weigh up against the impressive collection of writings released to describe German East Africa. He wrote that the Englishmen could find pride in the history surrounding Equatorial Africa’s exploration and may unselfishly admit their superiority of scientific work by the Germans in that region. Therefore, there is no mystery why the majority of important data for the Hehe history are German. After World War I, German East Africa split into Belgian and British empires and German scholars lost their interest. The British did not continue with research.

The tribe whom the Europeans would name Hehe lived on a southwestern Tanzania highland, to the northeast from Lake Nyasa (or Lake Malawi), in isolation. Tribe members only had a few forefathers who could be traced farther back than four Hehe generations. The Hehe people focused on agriculture. They had only a few pastors on the pastures, and a few tribal members kept limited numbers of goats and cattle. Despite occasional quarrels between chiefs, cattle raids, and broken alliances, the tribe lived a relatively peaceful existence in the beginning. No chiefdom had more than 5,000 members. However, by the mid-1900s, Nguruhe – a Muyinga dynasty led chiefdom with some importance – started throwing its force around to increase its power and influence.

Munyigumbe, who belonged to the Muyinga brood, initiated the start of states via conquest and marriage. Much of this occurred at the detriment of Wasangu after Sangu’s language and military tactics were used to perfectly inflame Hehe fighters to war. Under Merere II, Munyigumba also compelled the Wasangu tribe to transfer their metropolis to Usafwa.

Munyigumba passed away in 1878 – 79, and a civilian war began. Munyigumba’s brother-in-law, a Nyamwezi servant, managed to murder Munyigumba’s brother. Mkwawa, Munyigumba’s son, killed Mwumbambe (the Nyamwezi servant) at a place referred to as the location where human skulls piled up. Mkwawa became the primary dominator until the 1900s ended. In the book A Modern History of Tanganyika, John Iliffe represents Mkwawa as a slender man with sharp intelligence who was cruel and brutal with applause as the “madness of the year.”

Through intimidation and war, Mkwawa became the solitary dominator of the Hehe people by 1880 or 81. He continued to increase the Hehe reign throughout the north to the main caravan paths. He harassed the Germans, Wagogo, and the Wakaguru. Anyone who stood in their path, including their old foes, the Wasangu’s, were also afflicted in the east and south. The Wasangu’s started reaching out for German assistance. However, the Hehe tribe had the most dominant reign across the southeast by 1890. The conflict between them and the Germans, who were also a raiding power, occurred. While the Hehe did not have a detailed organization, they had the pliability to make life difficult for their oppositions.

Ihumitangu (where colonial warriors were trained) was established by the Subordinate Chief Motomakali Mukini “Mkini” during his reign. Galakwila Motomkali Mkini, his son, succeeded him.

Hehe Society

Uhehe is the primary home of the hehe people. It is situated between the Kilombero and Great Ruaha waterways within the Usungwa highlands and the tableland in the north segment of the Southern mountains. The area has a primary tableland overtaken with Brachystegia woodland, tall standing grasslands, rainforests, and underneath the northeast, west, and north cliffs next to branches of and the main Great Ruaha River, the area has arid plains covered in thorn scrubs.

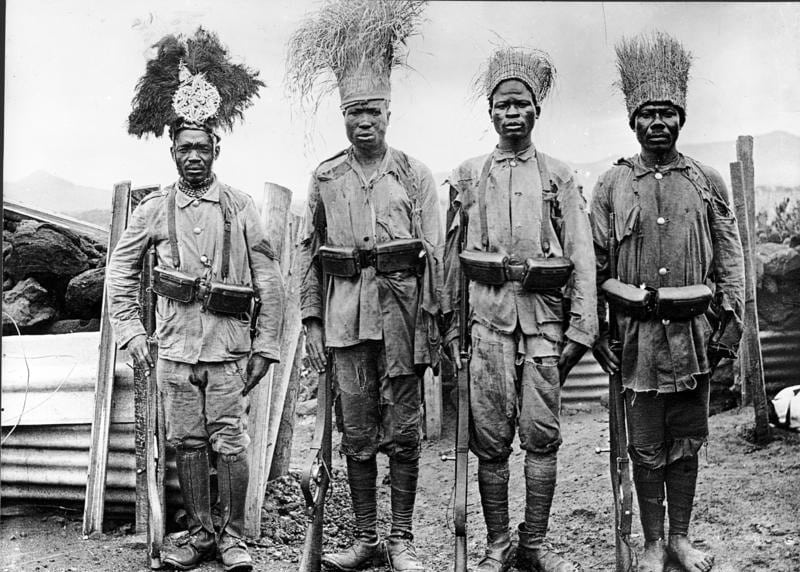

Colonial descriptions of the Hehe tribe often romanticized them by falling back on their outfitted hostility toward German East Africa. They were described as uncivil mountain people who were secluded and only lived for war. Descriptions stated that they were true soldiers who depended on spears and the discipline of their prepared citizens for power. It was said that even after guns became a standard war tool, the Hehe people continued to use the spear as their primary defensive weapon. They believed spears had an advantage on the open plains. A boma sheltered behind walls or palisades with guns was their weak point. They preferred tactics and unforeseen mass spear attacks.

Military structures continued as an essential part of the hehe being, and all adult males were called to be fighters. Semi-professional warriors were used for training the youngest ones in the metropolis, Iringa. The Hehe boasted with a direct following of approximately 2,000 – 3,000 males by the 1890s, with an additional 20,000 males of recruitment age ready to be deployed from their different areas. By the 1800s, these living regions were mostly bordered by extensive maize crops. The hehe only started building their homes closer to one another when warfare became a reality, and their military standing was not enough to offer them protection anymore. When the wars came to an end, their homes became more scattered again. Ideal homesteads each had a surrounding field, and large homes intended to house multiple wives were surrounded by open courtyards.

Lt. Nigmann thought the Hehe empire was sophisticated with its customs, legal systems, and traditions, while Iliffe considered it unsophisticated. However, all power originated from the chief and defeated chiefdoms merged due to brutal captures, fear, and force. Nevertheless, the Hehe state was durable and successful whether it was considered sophisticated or not. Visitors to the state have repeatedly commented that a unique sense of arrogant confidence was in the air, and the Hehe identity stood firm through all the colonial pressures the country has faced.

Influential men owned as much as ten or twenty women who were given to them after being captured in war. These women moved water and building materials to insulate their homes against harsh weather conditions and did nearly all the subsistence farming. Children born from these women received their family names (also known as praise names) and a list of the kinds of food they were forbidden from eating from their father. The Hehe tribe members were not allowed to marry anyone they shared a praise name or forbidden food with, even if their bloodline was untraceable. They were also prohibited from marrying anyone related to them along the female family line. However, a leaning towards marrying cousins was there, which led to multiple communities containing households with related members. An important cultural part of bride price that had to be exchanged to obtain a wife was a bull and two cows.

While headmen (judges) were tempted with bribery (and sometimes gave in), a recognized law enforcement system and courts existed. Although the punishments given had some variety, they remained relatively simple. Various retributions were in place, such as penalties or punishments, beatings, death sentences, and, while infrequently used, chiefdom expulsion. Besides the judicial execution, anything posing a risk to individual health, crippling, or failing was uncommon amongst the Hehe people. Light incidents such as property-related crimes, personal injury, adultery, etc., were overseen by the village headman. The more challenging incidents, such as those involving a test administered by poison, were advanced to the sultan. All incidents were represented orally and heard publicly, except trials concerning incidents where the sultan was betrayed. Incidents generally only required males as eyewitnesses, while up to five and no less than three eyewitnesses were needed if they were female.

Crimes that formed part of the judicial concept and could be punished included:

- Adultery (in these incidents, one female eyewitness was adequate, and a penalty of up to three cattle heads was given)

- Agricultural theft

- Deceiving or displeasing the state or the leader thereof

- Testifying false information

- Incest (very infrequently due to females marrying from ten and thirteen with the assistance of between three and five eyewitnesses)

- Manslaughter

- Murder

- Rape (the victim acted as the witness)

- Obtaining stolen goods

- Swindling

- Theft

- Vendetta

If a man and woman were to be divorced, the man had the option of taking all his weaned offspring from the woman, and bridal wealth had to be returned. Women generally obtained divorces after plans with a new man had already been made.

The state provided identity and unity through its power and strength, which was in its speared warriors. They made victorious and disciplined warriors and allowed all to reap in the success.

Check out one of the Wahehe songs here to get a sneak peak of how rich their culture is:

Hehe Rebellion

As the Germans built a station along the central caravan path between Tabora and the coast, the Hehe expanded towards the east and north. The Hehe looted, brutally attacked, and destroyed groups who recognized and accepted German supremacy by displaying the flag of Germany. After the Germans had pointless negotiations with the Hehe, they sent an expedition out under headman Emil von Zelewski‘s leadership.

Zelewski received permission to attack the Hehe after Julius von Soden predicted minor damage in doing so. Iliffe writes in A Modern History of Tanganyika and Holger Doebold in Emil Zelewski, with Lt. Tettenborn’s official report: The German Schutztruppe, that on the 17th of August 1891, their new commander, Zelewski, invaded the base at dawn leading the column on a donkey to secure the inland region with its direct communications and trade. In the book, Iliffe describes how they burned 25 large village homes and murdered three tribal warriors. He states that the Hehe fighters mainly had shields and spears and only a few guns. Iliffe writes that the Hehe’s were frightened away with only a few shots fired from their side. An officer fired his gun towards a bird as their center reached the waiting Hehe warriors. The warriors charged with their spears in hand, but one (possibly two) shots from the Askari were enough to overwhelm the Hehe. However, confusion occurred when the 5th company was stampeded by the pack of donkeys of the artillery rain after they panicked. Soon after that, the Askari also started to panic, and Lt. von Heydebreck escaped to a nearby tembe alongside Gaber and Morgan Effendi (two black officers), and twenty Askari.

Zelewski was speared by a teen who was only 16 while he still occupied his donkey. Within ten minutes, the column’s majority was defeated. Iliffe said that he retreated through the mayhem of running porters, plundering Hehe warriors, and withdrawing Askari’s as well. After the rearguard managed to escape, they neared a hill, occupied it, and raised their flag to rally survivors with a bugle call. Iliffe writes that he sent a patrol to assist the wounded Lt. von Heydebreck (who was covered in blood after being speared twice behind his left ear) to their position. On the 17th – 18th of August, NCO Thiemann passed away due to his wounds, and they buried him out of the Hehe sight at their tembe position.

The Hehe ignited the grass. They burned the injured and hoped to trap the rearguard. Approximately 300 to 400 Hehe’s followed those escaping but decided not to strike. They already departed with 60 of their own. Later, another 200 died from their injuries. The Germans drew back towards Kondoa. Iliffe writes that Lt. von Heydebreck (almost healed), Sergeant Kay, Morgan and Gaber Effendi, NCO Wutzer, 74 porters (seven of them wounded), 62 Askari (11 of them wounded), four donkeys, and their primary baggage was still together.

Lt. Tettenborn thought that if so many Hehe leaders (Mkwawa included incorrectly) had not died, nobody would have lived. He also stated that the main baggage was not retained since Zelewski started with field artillery, machine guns, 320 Askaris, 13 Europeans, and 17 carriers, of whom 256 Askaris, ten Europeans, and 96 carriers were lost. The Hehe were regarded as the mightiest warriors occupying German East Africa after defeating the Germans. The Schutztruppe could no longer attack the Hehe.

The new leader ruling German East Africa was Julius von Soden. He plotted revenge and stated that it would have been better had they devoured the inland only after digesting the coast. All journeys were banned for eighteen months, although the German army disapproved. However, Tom von Prince struggled with leaving the Hehe at peace and used his northern forts to invade the Hehe region from the south.

Colonol Freiherr von Schele reigned as the new ruler after 1893 when Soden left. He put policies of aggression in place, and the operation of Zugführer Bauer, Wynecken, and Prince in aid of Merere began. Before the Germans finally attacked in 1894 and took over Mkwawa’s metropolis, Iringa, caravan raids resumed due to failed negotiations. The Germans armed themselves with machine guns (3) and 609 Askari. However, they could still not capture Mkwawa, so the Hehe carried on with their attacks on those bordering them and killed the Germans. Only after Mkwawa committed self-slaughter did peace surround Uhehe.

While von Schele was repeatedly attacked by political moderators after he received praise for Mkwawa’s ultimate defeat and received Germany’s most high reward, Berlin finally put him under civilian supervise. After this, Schele resigned, and more peaceful officials followed him over the following two years. They nevertheless still pressured the Hehe.

After Mkwawa was defeated, Tom von Prince stated that the Hehe greatly offended him due to their refusal to identify the youth who killed Zelewski. Prince declared that a warrior who merely followed orders would never be punished by the German military.

The Hehe tribe split by 1896, and some even began submitting under the Germans. Mkwawa was secluded as an outcast, although always safe thanks to the common Hehe populace. Loyal Hehe people and Sangu soldiers of the Merere II’s son, Merere III, helped Mkwawa attack German outposts, ambush their patrols, and raid them. The Germans retaliated by increasing in numbers, searching again, and also executing those who helped Mkwawa. The Germans tried positioning a brother of Mkwawa as chieftain. However, they executed him after only two months because they blamed him for the continued attacks on their patrols.

In July 1898, Mkwawa killed himself at gunpoint after he was confined. The Germans beheaded him and sent his head to their country. Because the Hehe and Mkwawa became so notable, a clause ordering that his skull is taken back to Uhehe was put in the Versailles Treaty. After the remains were found in Berlin (not Bremen), it was returned to Kalenga (instead of Iringa) in 1956. However, the identification of the remains is still doubtful. Despite more than 100 years passing, Mkwawa is still known as a Tanzanian national hero.

While Tanzanian officials are still cautious, the Hehe have not rebelled again, not even after or during the Maji Maji Rebellion. Until today, the characteristics of the Hehe are still viewed as energy, intelligence, powers, a desire for strength, and suspicion.

For more articles on the Tanzania Tribes click here!