Critical Insight: Freedom of Religion in Tanzania

Freedom of religion in Tanzania describes the ability of Tanzanians to freely put their religious affiliations to practice, taking into consideration both societal attitudes and government policies towards various religious organizations.

The semi-autonomous Zanzibari government and the Tanzanian government both appreciate freedom of religion in Tanzania to be a key principle and have put efforts in place to preserve it. Zanzibar’s Muslim officials are appointed by the government of Zanzibar. The main judicial body is secular in both Zanzibar and Tanzania, but Muslims are allowed to go to religious courts in case of family-related matters. Both Muslims and Christians have faced isolated cases of violence motivated by religion.

The ideology and policies of Ujamaa introduced by the first government of Tanzania post-independence stressed national unity instead of ethnic and religious division, which is reflected in the anti-discriminatory rhetoric in the constitution of Tanzania, which is still in operation since 2019. Even though Ujamaa was discarded by the government in 1985, and religious division has increased since then, NGO and academic sources give credit to Ujamaa for its contribution to religious freedom as well a social stability in the country.

Demographics Related to Freedom of Religion in Tanzania

A Pew Forum survey in 2010 approximates that about 61% of Tanzania is Christian while about 35 percent are Muslim and another 4% belong to other minority religious groups. Another Pew Forum Report in 2010 approximates that over half of Tanzanians have integrated elements of the traditional African religion in their lives. No local surveys have been done to cover religious affiliations.

Large communities of Muslims are located in the coastal regions of the mainland, with a few of them situated in inland urban areas. The country’s Christian denominations include Protestants, Roman Catholics, Seventh-day Adventists, Jehova Witness, Anglican church of Tanzania and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Other groups are Hindus, Buddhists, Baha’is, animists, Sikhs, and people who do not have a religious affiliation. In Zanzibar, about 99 % of its 1.3 million residents practice Islam, two-thirds of whom are Sunni as per the Pew Forum report of 2012. The rest comprise many Shia groups, mainly of Asian ethnicity.

History

Background Involving Freedom of Religion in Tanzania

Tanzania consists of two areas, the Tanganyika mainland and the Zanzibar archipelago, which were united in the 1960s. Tanganyika was initially mapped out as part of the African partition in the 1884 Berlin Conference. On the other hand, Zanzibar has been a distinct region since the 13th century, while it was inhabited by Swahili states.

The precise dates when Islam was introduced are unclear, however, the first proof of their presence goes back to 830 CE, several Muslim city-states were built along the coast of the mainland and in Zanzibar. The city-states peaked in the 15th and 14th centuries. The Portuguese reign in Zanzibar was short before they were dethroned by the Omani Empire, that eventually relocated its administration to Zanzibar. In the early 19th century, the archipelago became an important factor during the slave trade, that would continue up to the early period of the 20th century. Christianity came to the mainland in the 19th century through various missions while Sufi missionaries spread Islam around the same period beyond the coast. Both Muslim and Christian practices are influenced heavily by traditional African religious practices.

During the push for independence, both Muslims and Christians played an important part in the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU). However, the course shifted after independence, and the Muslim and Christian communities were at times depicted as being at odds politically.

The Zanzibar Revolution and Early Independence (1961-1964)

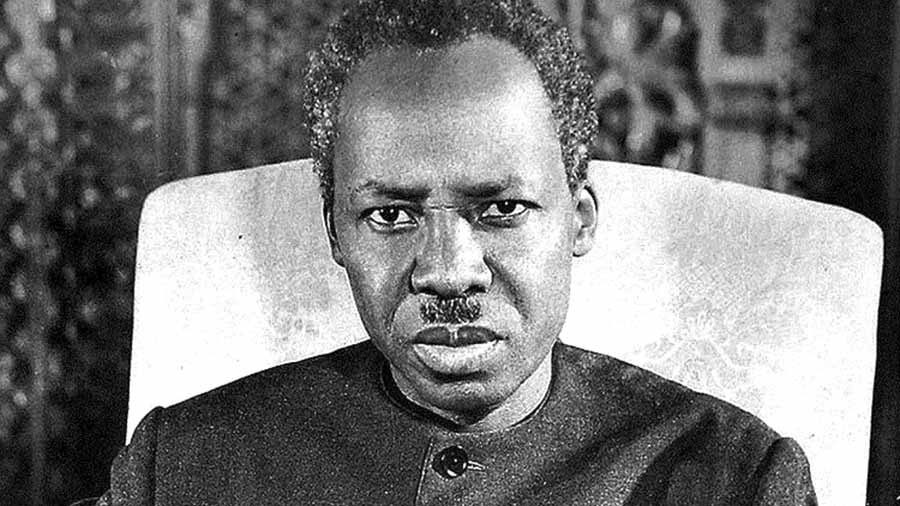

British rule in Tanganyika ended in 1961, and in 1962, Julius Nyerere became the country’s first president, while Zanzibar remained a British protectorate under the rule of an Arab king. Zanzibar’s Sultanate was deposed during the Zanzibar Revolution of 1964 in which African rebels used tremendous violence against Arabs and South Asians, who were primarily Muslim or Hindu, throughout the revolution and associated with the Sultanate of Zanzibar’s ruling class. The event’s legacy is a subject of debate, as sections of Zanzibar’s population consider the harsh and racially motivated violence as revenge for persecution suffered during the rule of the Sultanate, which had a substantial slave trade. John Okello who believed it was his role as a Christian to free Zanzibar from “Muslim Arabs,” led the forces that perpetrated the bloodshed, despite the Africans in the Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP) and Zanzibar being mostly Muslim. The actions of Okello and militant Christians excluded other members of the ASP, and soon, Okello was marginalized, demoted, and deported.

Freedom of Religion in Tanzania During Ujamaa and Unification (1964-1985)

Tanzania was formed after the revolution when Zanzibar and Tanganyika merged to become Tanzania, with Julius Nyerere as the first president. The religiously diverse rulers on the mainland preferred a secular government, although Zanzibar preserved some autonomy and developed a semisecular government. Even though Islamism was not formally recognized as a national religion, it was afforded special recognition and benefits. Therefore there somewhat a decent amount of freedom of religion in Tanzania at that time already.

Tanzania shifted more to the left in its politics in 1967, when it started promoting Ujamaa, a socialist philosophy that emphasized equality, unity, and freedom of freedom as its chief principles. In addition, the country instituted a constitution that included strong anti-discrimination provisions, inclusive of religious discrimination. Human Rights Watch recognizes Ujamaa as a successful national unity model that contributed to the country’s relative social harmony and stability, with the proviso that the insistence on national unity made it a challenge to look into human rights violations at times. Tanzania is the sole nation in the East African region yet to experience chronic religious, political, or ethnic violence since it attained its independence.

Freedom of Religion in Tanzania After Nyerere (1985- Present)

After Nyerere retired from politics at the end of his term in 1985, Ujamaa was virtually abandoned by the Tanzanian government as its philosophy, although the constitution implemented in 1977 is still in force as of 2019. Since the Ujamaa philosophy ended, tensions have risen between the government and Muslims, and even between, Christians and Muslims. Tensions between the state security personnel and Muslims reached a point of violence in 1993 and 1998, with both occurrences ending in numerous deaths. According to academics worldwide, the failure of the Ujamaa ideology in terms of both its social wellbeing policies and national-unity goals, the impact of the rise in worldwide religious militancy during the dusk of the twentieth century, and as the twenty-first century was beginning, religious rejuvenation movements within Tanzania, as well as the reconfiguration of political camps after the economy‘s deregulation towards the end of the 1980s, are to blame for the deterioration in religious harmony and freedom of religion in Tanzania in general.

In 2015, witchcraft was declared illegal. However, there were still reports of witchcraft-related ritual deaths in 2019, with authorities detaining persons suspected of being involved.

Religious violence is uncommon, yet it does happen. Three incidents of property destruction and vandalism, inclusive of arson, against the clergy and religious structures were reported in 2017.

Legal Framework

Both the Tanzanian union government’s constitution and Zanzibar’s constitution prohibit religious profiling and guarantee freedom of religion in Tanzania. The founding of religious political outfits is prohibited by law. It is also illegal to take any actions or make any statements to offend another person’s religious beliefs. Anyone found guilty of such a crime faces a year in prison.

Religious affiliation is not indicated on Tanzania passports and vital documents by the government. If a person is obliged to give sworn testimony, police records must include their religious membership. Religious affiliation must be specified on medical care applications so that special religious customs can be honored. The law mandates that the government keep track of each prisoner’s religious affiliation and provide worship facilities for them.

Muslim Community’s Leadership

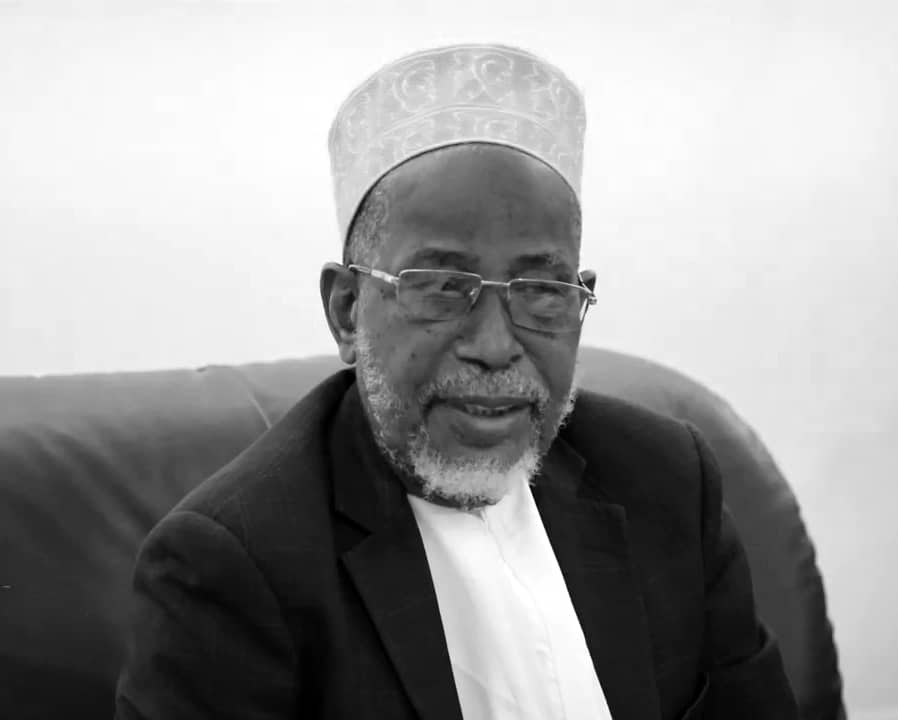

Tanzania’s National Muslim Council appoints the mufti on the mainland. On Zanzibar, the mufti is appointed by the President and is a Muslim community leader as well as a public worker aiding with the affairs of the local government. All Islamic events are nominally approved by the Mufti of Zanzibar, which also regulates all mosques on the island. The mufti also oversees the importing of Islamic material from other regions to Zanzibar and certifies religious lectures taught by visiting Muslim clergy.

Religious and Secular Courts

In both civil and criminal matters on the mainland, Christians and Muslims are governed by secular laws. The law respects customary practices, that may include religious customs, in family-related situations concerning the adoption of minors, inheritance, divorce, and marriage. In such instances, some Muslims prefer to seek religious leaders rather than file a lawsuit. In cases of divorce, child custody, inheritance, and other Islamic law-related issues, Muslims in Zanzibar can choose to present to a qadi or civil (Islamic judge or court). All cases handled in courts of Zanzibar can be appealed to the Union Court of Appeals situated on the mainland, except for those involving Zanzibari sharia and constitutional matters. The chief justice of Zanzibar together with five more sheikhs make up a special court that hears appeals from Zanzibar’s qadi courts. Zanzibar’s president chooses the chief qadi, acknowledged as the top Islamic expert responsible for Quran interpretation, and supervises the qadi courts. The mainland has no qadi courts.

Education

Religion may be taught in public schools, however, it is not included in the national curriculum. Such classes are given occasionally by volunteers or parents and must be approved by the school administration or parent-teacher groups. In order for administrators to assign kids to the relevant religion class if available, public school registration forms must include a child’s religious affiliation. Religious classes are optional for students. Students in public schools are permitted to put on the hijab but the niqab is prohibited. In short, there is a high level of freedom of religion in Tanzania in many aspects.

For more articles related to Laws of Tanzania (Acts), click here!