Swahili Language – History, Classification, Phonology and More

Swahili, or Kiswahili, is Bantu language native to the Swahili people. It is among the two sanctioned languages (English is the second) of the countries that make up the East African Community (EAC), including Kenya, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda, and South Sudan.

In this article we’ll explore the unique history of the Swahili language, explain the phonology and classification and even provide some word examples!

We’ll also include multiple translation tools you can use and teach you how to say swahili thank you, swahili freedom, and many other english and swahili words and phrases!

About Swahili

This language is the lingua franca in most areas of the Great Lakes area in Africa, East and Southern parts, such as Malawi, Congo-Kinshasa, Somalia, Zambia, and Mozambique. Swahili is among the working languages of the African Union (AU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC). The precise population of Swahili speakers, including native speakers or those who speak it as a second language, is between 50 and 150 million.

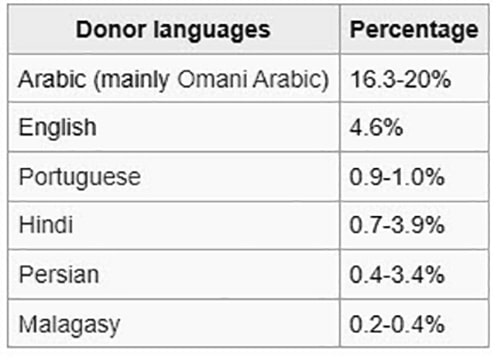

About 16 to 20% of Swahili words includes Arabic words, such as Swahili, sawāḥilī (سَوَاحِلي, in the plural to mean ‘from the coast‘) in Arabic. The Arabic words started from the connection of Arabian merchants with Bantu dwellers along the coast of East Africa throughout various centuries, the same period when Swahili appeared as the lingua franca.

By 2018, South African schools were legalized to teach Swahili as a non-compulsory subject beginning in 2020. Botswana did the same in 2020, while Namibia is planning to follow suit. Shikomor (also known as Comorian), Comoros’ official language, also used in Mayotte as Shimaore, has a close relation to Swahili, occasionally taken to a Swahili dialect, despite other authorities taking it to be a separate language.

Swahili City States

The Swahili City-States were a series of independent commercial city-states that emerged along the East African coast, from Somalia in the north to Mozambique in the south, during the medieval period. These city-states were characterized by a cosmopolitan culture that was influenced by Arab, Persian, Indian, and African traditions.

Swahili Language Classification

Swahili belongs to the Bantu language’s Sabaki branch. According to the geographic classification by Guthrie, Swahili belongs to Bantu Class G. In contrast, the rest of Sabaki languages belong to Class E70, popularly known as Nyika. Ancient linguists never considered the influence of the Arabs on Swahili as significant. Since Arabs only influenced lexical items. Many of which were borrowed were only from 1500, while the syntactic and grammatical make up of the language is generally Bantu.

History

Etymology

The word Swahili has an origin with a phonetic resemblance in Arabic:

Ancestry

The gist of Swahili comes from Bantu languages along the East Africa coast. A great deal of Swahili includes Bantu lingo with cognates in Taita, Mijikenda, and Pokomo languages, and other Bantu languages in EA to an extent.

Although views differ regarding the specifics, there have been historical allegations. Around 20 percent of the Swahili words came from foreign words. Most Arabic, including other contributing dialects, such as Portuguese, Persian, Malay, and Hindustani.

Most Arabic words in Swahili come from Omani Arabic. “Early Swahili History Reconsidered” in the Script. Nevertheless, Thomas Spear revealed that Swahili preserves most vocabulary, sounds, and grammar acquired from the Sabaki language.

While noting regular vocabulary, relying on one hundred word lists, 72 to 91 percent Sabaki words (reportedly the parent language). In contrast, 4 to 17 percent were phrases from other languages in Africa.

Just 2 to 8 percent were from languages away from Africa, and Arabic words made up were part of this percentage. From other sources, about 35 percent of Swahili vocabulary is from Arabic. What remained missing from consideration was that many foreign terms had local similarities.

The preference to use words borrowed from Arabic prevailing on the coast, with natives, in a traditional portrayal of closeness to, or ancestry from Arab tradition, would yearn for the use of borrowed words, while the indigenous people inland use the local similarities.

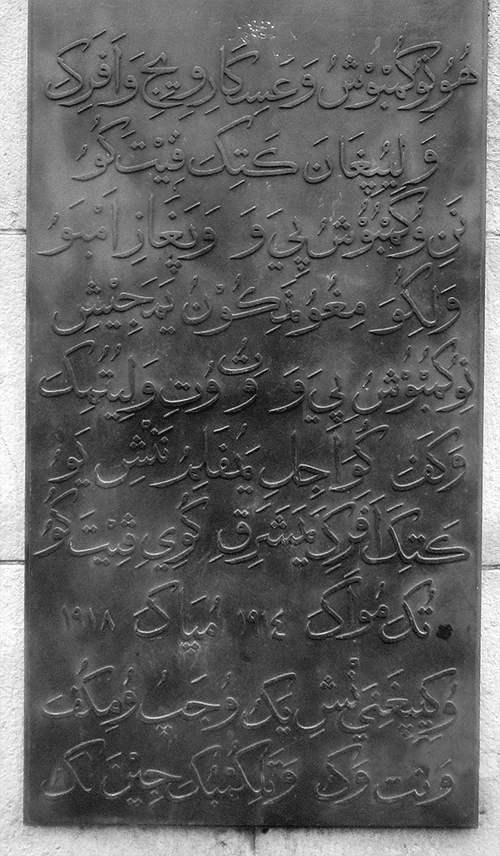

This writing first appeared in Arabic writing. The first recognized documents inscribed in Swahili included letters penned in Kilwa (Tanzania) by 1711 in Arabic Script. These were for sending to Mozambique Portuguese and local associates. Preserved initial letters are in the Historical Records in Goa, India.

Colonial Period

Different colonial masters who ruled the East Africa coast played a part in the spread and growth of Swahili. After the Arabs arrived in East Africa, they used Swahili for trade and teaching Islam to the indigenous Bantu people. This led Swahili to get written first using the Arabic alphabet.

Future Portuguese contact led to an increase in the Swahili language vocabulary. The formalisation of the language at the institutional level was after the Germans gained power following the conference in Berlin.

After realizing that Swahili was widespread, the Germans sanctioned it as the language for use in schools. So, Swahili schools were known as Shule (from the German word Schule) in trade, the courts, and the government.

While the Germans controlled the East Africa region, where the majority were Swahili-speakers, the alphabet was changed to Latin from Arabic. Following World War I, the British annexed German East Africa and discovered Swahili widespread in many areas, away from the areas on the coast.

The British legalized Swahili for use all over the East Africa region (even though British East Africa [Uganda and Kenya], many places used English, diverse Nilotic, and more Bantu dialect as Swahili was mainly confined on the coast).

By June 1928, representatives from Tanganyika, Uganda, Zanzibar, and Kenya converged in Mombasa for an inter-territorial conference. Swahili from Zanzibar was selected as the standard for these areas, including adopting the standard Swahili orthography.

Current Situation

Swahili is now the second language millions of people speak in the countries of Africa’s Great Lakes region (Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya). It’s the national or official language and the native language for various people across Tanzania. Especially those living in areas on the coast of Pwani, Tanga, Lindi, Dar es Salaam, and Mtwara.

In Tanzania inland, people speak Swahili with a pronunciation swayed by local dialects and languages, including the native language for many city-borns. People inland speak Swahili as bilingual speakers.

Swahili, including other languages with a close relation, is spoken by a relatively few people in Malawi, Burundi, Mozambique, Comoros, Rwanda, and Zambia. Still, Swahili was accepted on the Red Sea’s southern ports by the twentieth century. Swahili speakers might be between 120 and 150 million altogether.

Swahili is one of Africa’s first languages for developing technology applications. Among the early developers was Arvi Hurskainen. Some of the applications were a spell checker, language learning software, tagging parts of speech, 25 million words text corpus for Swahili analysis, e-dictionary, and machine translator for Swahili to English. Language technology development also strengthened Swahili’s position for use in modern communication.

Tanzania

Swahili’s extensive use as Tanzania’s national language started after the country got independence in 1961. The new government chose to use Swahili as the language for unifying the new state. This led to using the language in various levels of trade, government, art, and schools with teaching Swahili to children in primary school, afterward turning to English (mode of training) for Secondary schools (despite continuously teaching Swahili as a subject on its own). After the unification of Zanzibar and Tanganyika in 1964, there was the establishment of Taasisi ya Uchunguzi wa Kiswahili (TUKI) from the Interterritorial Language Committee (ILC), an institute for Swahili research.

By 1970, there was merging of TUKI with Dar es Salaam University, to form Baraza la Kiswahili la Taifa (BAKITA). It was an organization for developing and advocating Swahili for Tanzania’s national integration.

Fundamental activities authorized for the body include:

- Forming a conducive environment for the promotion of Swahili.

- Promoting Swahili use in business and government functions.

- Coordination of activities for other bodies concerned with standardizing the Swahili language.

BAKITA’s vision include:

- Efficient management and coordination of Kiswahili use and development in Tanzania

- Full participation and effective promotion of Swahili in East Africa, Africa including the whole world.

Even though other agencies and bodies can nominate new vocabularies, only BAKITA can authorise its use in Swahili.

Kenya

In 1998, there was the establishment of Chama cha Kiswahili cha Taifa or CHAKITA in Kenya to propose and research ways to integrate Kiswahili into a nationwide language and make it mandatory in schools that same year. However, many young people speak a Swahili variety known as “Sheng” in regular conversations. It is prevalent everywhere that standard Swahili sounds literary and archaic now.

Religion and Political Outlook

Religion

The development of Islam and Christianity in East Africa relied heavily on Swahili. Since arriving in East Africa, the Arabs introduced Islam and established Madrasas for teaching Islam to natives in Swahili. With the growth of Arab presence, multitudes of natives switched to Islam with teachings in Swahili.

Since the Europeans’ arrival in EA, there was the introduction of Christianity in the region. As the Arabs mainly occupied the areas on the coast, missionaries from Europe ventured deeper inland to spread Christianity. However, since the initial missionary bases in East Africa were along the coast, missionaries learned Swahili. They applied it in spreading Christianity for having various similarities with other native local languages.

Politics

Swahili was the language for organizing the masses and political movement throughout Tanganyika’s independence struggle. They used the language for radio broadcasts and publishing pamphlets to mobilise the masses to demand independence. Swahili became the country’s national language after independence.

Today, Tanzanians are proud of Swahili, mainly when used for uniting more than 120 tribes in the country. Swahili was applied to enhance solidarity in the people and togetherness. So, Swahili is still a strong identity for Tanzanians.

Phonology

Vowels

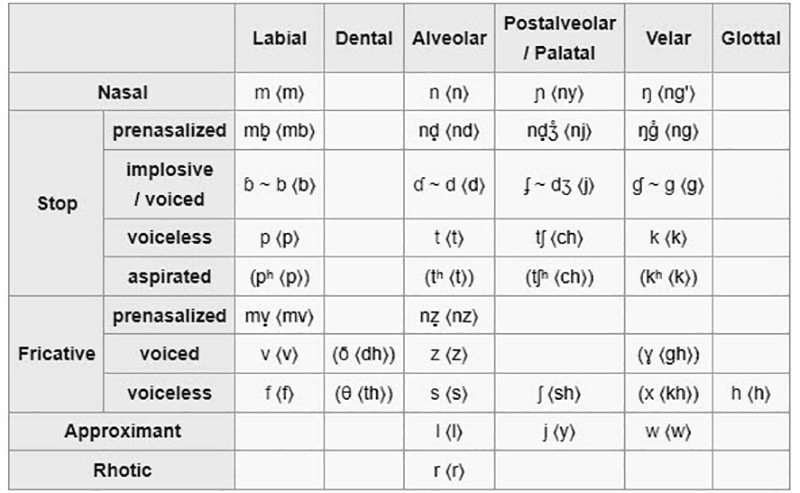

Regular Swahili alphabet has five vocal sound phonemes: ɑ, ɛ, i, ɔ, and u. Ellen Contini-Morava revealed that reducing vowels is impossible, despite the stress. Nevertheless, Edgar Polomé revealed that the five phonemes have different pronunciations. To Polomé, pronouncing ɛ, I, ɔ, and u requires stressing syllables.

For syllables not stressed, and ahead of a prenasalized consonant, pronunciation is e, ɪ, o, and ʊ. The typical pronouncement for E in mid-position follows W. Polomé asserts that pronouncing ɑ is just after W, the pronunciation is (a) in other situations, mainly to follow /j/ (y). The pronunciation for A is [ə] when in the final position of a word.

Swahili vowels are long; written as double vowels (for instance: kondoo, to mean “sheep”). Because of the historical process where L is eliminated amongst two instances of a similar vowel (the pronunciation for Kondoo was Kondolo, applied in particular dialects). Nevertheless, the long vowels don’t seem phonemic. The exact process happens in Zululand.

Consonants

Some Swahili dialects potentially also have articulated phonemes regardless of not being marked in the orthography of Swahili. Different research prefers distinguishing prenasalization like clusters of consonants, outside of being separate phonemes. Traditionally, nasalization is lost ahead of voiceless consonants. Later on, the pronounced consonants become voiceless, yet still being written as mb or nd.

Phoneme (r) is executed as a brief trill (r) or popularly as one tap [ɾ] according to the majority of speakers. (x) is available in free deviations with h, while only some speakers can distinguish it. In some words borrowed from Arabic (verbs, adjectives, nouns, ), intensity or priority is portrayed by repeating the initial emphatic consonants ( sˤ, tˤ,dˤ, zˤ) including the uvular (q), or prolonging a vowel, in place of using aspiration acquired from Bantu words.

Orthography

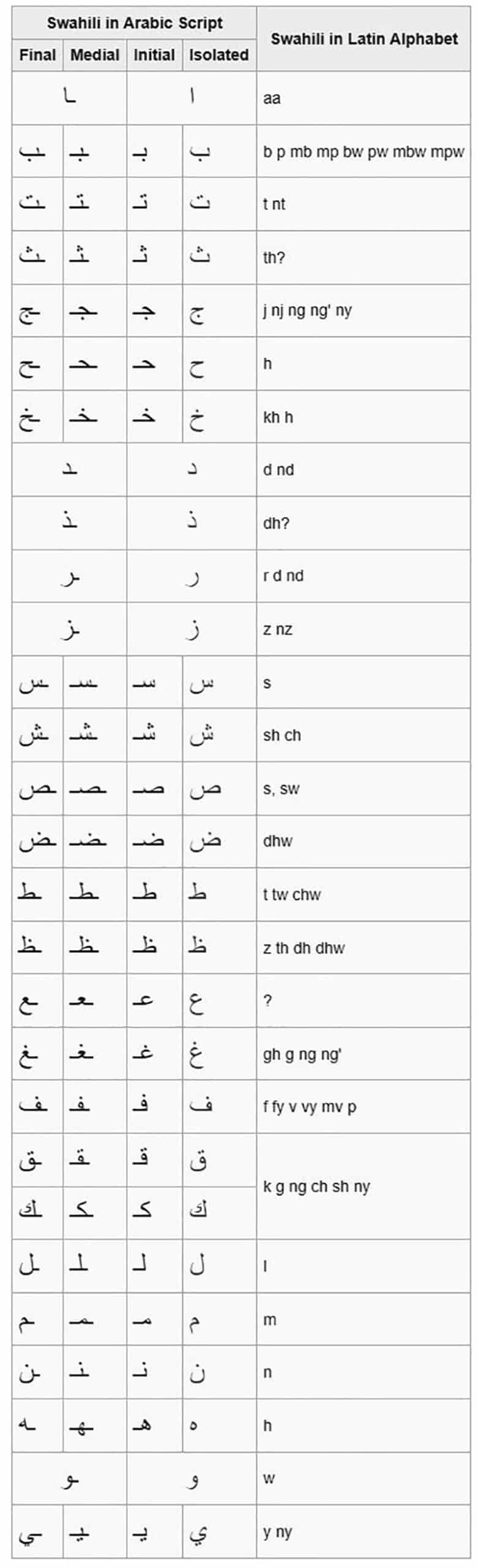

Writing Swahili today relies on the Latin writing system. Some digraphs exist for local sounds, ch, ng, sh including ny; x and q not utilised. There is no use of c except in the ch digraph and unassimilated English borrowed words. Sometimes, as an alternative for k for adverts. Various letters of Arabic sound that most non-ethnic Swahili-speaking areas find hard to differentiate.

Arabic Script was first applied to write Swahili. Contrary, adopting Arabic Script in more languages, there was relatively insignificant accommodation for Swahili. Variations also exist in orthographic conventions among authors and cities. Over centuries, some have been somewhat precise while others differ enough to stimulate intelligibility difficulties.

(o), (u), (e), and (i) were usually conflated, however in other spellings, distinguishing /e/ from /i/ existed with a kasra 90° rotation while distinguishing /o/ from /u/ happened by inverting damma writing.

Various Swahili consonants lack Arabic equivalents, and they usually lack unique letters created, unlike, for instance, Urdu script. Alternatively, the closer Arabic sound works for a substitute. Apart from meaning that a single letter usually stands for various sounds, writers made multiple options for alternative consonants.

The following include some Roman Swahili and Arabic Swahili equivalents

That was for the ordinary situation, though some authors adopted Urdu conventions to differentiate aspiration including (p) from (b): پھا (pʰaa) ‘gazelle’, پا (paa) ‘roof’. Despite not existing in ordinary Swahili currently, alveolar and dental consonants have a distinction in other dialects, portrayed in particular orthographies, for instance, كُٹَ –kuta ‘encounter’ versus كُتَ –kut̠a ‘contented’.

A k having y dot, ـػـػـػـػ, utilised for ch during particular conventions; historical use of ky and even in modern times a more precise transcription compared to ch in Roman. In Mombasa, using Arabic emphatics to represent Cw was famous, for instance, صِصِ swiswi (typical sisi) ‘us’ with كِطَ kit̠wa (regularly kichwa) ‘head’.

Particles like ya, si, na, ni, kwa, are combined with the next nouns, possessiveness including yako and yangu connected to the previous noun. However, two-word verbs are written, having the tense–modality–aspect and subject morphemes split from the root and object, just like in aliyeniambia “the one who informed me”.

Grammar

Noun Forms

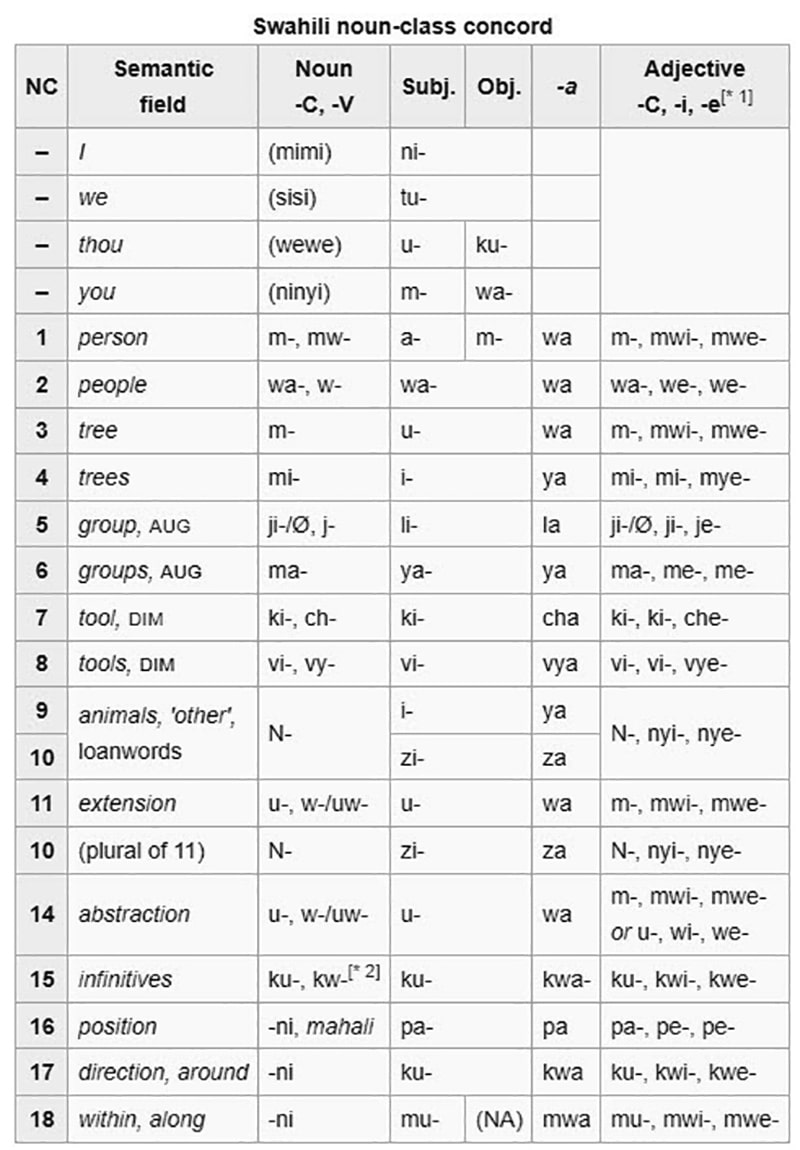

There’s the separation of Swahili nouns into forms, nearly analogous to sexes in more languages. Swahili prefixes denote factions of the same items: ⟨m-⟩ denotes a person (mtoto ‘little one’), ⟨wa-⟩ represents multiple people (watoto ‘little ones’), ⟨u-⟩ means abstract adjective (utoto ‘infancy’), et cetera et cetera.

Additionally, as pronouns and adjectives have to conform with the sex of the nouns in other languages having grammatical sex, therefor in Swahili pronouns, adjectives, including verbs, have to concur with nouns. A characteristic element for all languages of the Bantu.

Semantic Motivation

Historically, the ki-(vi- Grade included two different artifacts (Bantu Grade 7/8, mostly hand tools and utensils), diminutives (Bantu Grade 12/13), genders, conflated at an ancient stage to Swahili. Instances of the preceding include:

- Kiti “chair” (out of mti “tree, timber”).

- Kisu “blade”.

- Chombo “vessel” (whose extension is ki-ombo).

Instances of the preceding include kitawi “petal”, out of tawi “branch”; chumba (ki-umba) “chamber” out of nyumba “home” and kitoto “baby” out of mtoto “infant”. There’s an extension of diminutive sense. A contraction synonymous with diminutives in various languages is estimation and resemblance (bearing a fraction of character, as -ish or -y in English).

An example is kijani “green” out of jani “leaf” (compared to ‘leafy’ in English ), kichaka “thicket” out of chaka “clump” including kivuli “shadow” out of uvuli “shade”. A fraction of a verb is an action, for instance. Such instances (occasionally inactive ones) are available: kifo “passing”, out of the verb -fa “pass on”; kiota “birdhouse” out of -ota “to hatch”; chakula “food” out of kula “consume”; kivuko “afford, a pass” out of -vuka “traverse”; including kilimia “Pleiades”, out of -limia “planting with”, out of its purpose during planting.

A similarity, or a fraction of something, portrays marginal status during categorisation, so items that are marginal samples in their grade might use the ki-(vi- names. Chura, pronounced as ki-ura meaning frog, is a good example, it is partly terrestrial to make it a marginal animal. The extension is applicable for disabilities too: kilema “disabled”, kipofu “visually impaired”, kiziwi “hearing-impaired”.

Lastly, diminutives usually imply contempt, which is sometimes against non-dangerous things. This seems to be the traditional meaning for kifaru “rhino”, kiboko “hippo” (potentially initially meaning “stubby legs”), and kingugwa “spotted hyena”.

Another grade with varied semantic augmentation is the m-(mi- (Bantu grades 3/4). Usually known as the ‘tree’ Grade, with mti, miti “tree or trees” as a regular example. Nevertheless, it potentially includes essential entities not human or regular animals: trees with more plants, including mtama ‘millet’ (going on, plant-made things, for instance, mkeka ‘mat’) and mwitu’ forest’; natural and supernatural forces, including mwezi’ moon’, mto ‘river’; mlima ‘mountain‘, active items, including moto ‘fire’, inclusive of functional parts of the body (mkono ‘hand or arm’, moyo ‘heart’); including human groups, essential however not alive, like mji’ village’, including, through resemblance, mzinga’ cannon or beehive’.

Out of the critical idea of a tree, tall, spreading, and thin, arises an expansion to more extended items or components of items, including moshi ‘smoke’, mwavuli ‘umbrella’, msumari ‘nail’; including from action there still come active instances of verbs, including mfuo “metal fabrication” out of “to fabricate”, or mlio “sound” out of -lia “to create a ,I ound.

Words might be linked to their grades by metaphors. For instance, mkono is a functioning part of the body, while mto is a natural dynamic force, however, they are both thin and long. Items with a course, including mwendo ‘journey’ and mpaka’ border’, are identified with long and narrow things, just like in various other languages having noun classes. It might be further protracted to anything concerning time, like mwaka ‘year’ including potentially mshahara’ wages’. This class might put animals remarkable in some manner and not match the rest of the types so easily.

The rest of the classes possess foundations that might initially seem the same counterintuitive. In brief,

Class 1–2 includes various words regarding people: professions, kin terms, ethnicities, etc., having interpretations of majority English words that end with -er. These include some generic animal words: mdudu ‘bug’ and mnyama’ beast’.

Class 5–6 include a varied semantic array of expanses, groups, and augmentations. Even though interrelated, illustration is easier when separated into bits:

Augmentatives, including joka’ serpent’ out of nyoka’ snake‘, precede to titles including more categories in respect (diminutive opposites, that lead to contempt terms): fundi’ craftsman’, Bwana ‘Sir’, kadhi ‘judge’, shangazi’ aunt’.

Spaces: bonde ‘valley’, ziwa ‘lake’, anga ‘sky’, taifa ‘country’,

leading to, mass nouns: vumbi ‘dust’ (including other liquids with fine particles that might cover large expanses), maji ‘water‘, mali ‘riches’, maridhawa ‘in plenty’, kaa ‘charcoal’,

Collectives: kabila ‘ethnic group/language’,kundi ‘group’, daraja ‘ stairs’, jeshi ‘army‘, manyoya ‘feathers or fur’, manyasi ‘weeds’, mapesa ‘little change’, marimba ‘xylophone’ (various keys), jongoo ‘millipede’ (various legs),

from this, separate things in groups: tawi ‘branch’, jiwe ‘stone’, tunda ‘fruit’ (same name for most fruits), ua ‘flower’, mapacha ‘twins’, jino ‘tooth’, yai ‘egg’, tumbo ‘stomach’ (compared English “guts”), as well as double body parts including bawa ‘wing’, jicho ‘eye’, etc.

More dialogic or collective actions that happen in factions: neno ‘a word’ out of kunena ‘to say something (including by elongation, mental expressed processes: maana ‘meaning’, wazo ‘thought’,); pigo ‘a strike, blow‘ out of kupiga ‘hit’; shauri’ advice, plan’, gomvi ‘quarrel’, kosa ‘blunder’, jambo ‘liaison’, malipo ‘payment’, jibu ‘response’, agano ‘promise’, penzi ‘love’.

From pairing, another suggested extension for reproduction (egg, fruit, testicle, twins, flower, etc.). However, these usually copy various subcategories above.

Class 9–10 include mainly regular animals: samaki ‘fish’, ndege ‘bird’, and the particular names of common birds, bugs, and beasts.

Nevertheless, it is the ‘additional’ grade for words that don’t fit right elsewhere. Around half the nouns in this class are borrowed from other countries. Borrowed words might be categorized as belonging to this class for lacking the prefixes natural in the rest of the classes. Additionally, many native 9–10 class nouns lack a prefix. Therefore, they never create a consistent semantic style yet remain semantic augmentations from separate phrases.

Class 11 (considers the plural of class 10) are mainly nouns having a “prolonged shape outline”, in a single or double proportion:

mass nouns which are usually localised instead of taking up huge expanses: wali’ boiled rice, uji ‘porridge.’

Varied: ukucha ‘fingernail’, ukuta ‘wall’, wavu ‘net’, upande ‘angle’ (≈ ubavu ‘rib’), footprint’, ua ‘fence, yard’, wayo ‘sole, uteo ‘basket for winnowing’.

extended: utepe ‘stripe’, utambi ‘wick’, ubavu ‘rib’, ufa ‘crack’, uta ‘bow’, unywele ‘hair’ out of ‘a hair’, singulr nouns, usually class 6 (‘collectibles’) in plural: uvumbi ‘a speck of dust’, unyoya ‘a feather’, ushanga ‘a bead’,

Class 14 includes abstractions, like utoto ‘infancy’ (out of mtoto ‘infant’) including without plural. These have similar prefixes with concord class 11, apart from optional for adjectival agreement.

Class 15 is for oral infinitives.

Class 16–18 includes locatives. Bantu nouns in these classes are lost. The only lasting member in Arabic is Mahali ‘location(s)’, however among the Swahili in Mombasa, the ancient prefixes exist: mwahali’ places’ pahali ‘place’.

Nevertheless, a noun having the regional suffix -ni has classes 16–18 convention. A difference between them is that class 16 accord applies if the area is definite (“at”). For class 17, whether indefinite (“around”), alternatively requires movement (“to, toward”), with class 18. Whether it includes containment (“within” ): mahali kuzuri ‘wonderful place’, mahali muzuri (it is wonderful there), mahali pazuri ‘a great spot’.

Borrowed Words

Borrowings might or might not get a prefix matching the semantic grade where they belong. For instance, دود dūd in Arabic for insect or bug acquired from mdudu, in plural wadudu, having grade 1/2 prefixes wa- and m-, however فلوس fulūs in Arabic means fish scales, in plural or فلس fals) with English sloth are borrowed as just fulusi to mean fish (mahi-mahi) including slothi (“sloth”), without prefix related with animals (regardless of whether class 1/2 or 9/10).

During the naturalization of borrowings in Swahili, borrowed words are usually translated or analyzed again, like they already have a Swahili grade prefix. During this case, there is a change of the interpreted prefix with the regular rules.

Check the following Arabic loan words:

Kitabu is written in Swahili out of كتاب kitāb(un) in Arabic “book” (in plural كتب kutub; out of the Arabic root k.t.b meaning “write”). Nevertheless, the Swahili word for “books” in the plural is vitabu. Matching Bantu grammar, with ki- from kitabu analysed (interpreted) again, just like a nominal grade prefix with the plural vi- (grade 7/8).

معلم muʿallim(un) in Arabic is (“teacher” or معلمين muʿallimīna in plural) elucidated with the mw- class 1 prefix, to become mwalimu (walimu in plural).

مدرسة madrasa is a school in Arabic for singular (مدارس madāris in plural) elucidated as grade 6 in plural madarasa (darasa in singular).

In a similar light, wire in English and وقت waqt (“time”) in Arabic were interpreted to be with class 11 prevocalic beginning with w-, to become waya (nyaya in plural) and wakati (nyakati in plural)

Agreement

Swahili phrases correspond with substantives in the concord system; however, for a noun referring to a person, they agree with nouns from 1–2 classes disregarding the class of the noun.

Verbs concur with the class noun class and their objects and subjects s: prepositions, adjectives, and demonstratives concur with the class noun of their substantives. According to the dialect in Zanzibar, regular Swahili (sanifu in Kiswahili) is a rather complex system. But, it is highly simplified in multiple indigenous variations where Swahili is a second language, for instance, in Nairobi.

For bilingual Swahili, agreement portrays only animals: human items and objects spark m-, a-, and wa-, wa- in oral agreement, as non-human items and objects regardless of class spark zi-, and i-. Infinitives differ from regular ku- and lowered i-. (“Of” is invigorated wa including inanimate za, ya)

In regular Swahili, human items and objects regardless of class spark animacy consonance in m-, wa- and a-, wa-. Including non-human entities and things that spark various gender-consonance prefixes.

Dialects Including Languages with Close Relation

What Countries Speak Swahili?

Swahili is a Bantu language widely spoken in East and Central Africa. It is the official language of several countries, including:

- Tanzania

- Kenya

- Uganda

- Democratic Republic of Congo

- Rwanda

- Burundi

- Mozambique

- Somalia

- Comoros

- Mayotte

Dialects

Contemporary standard Swahili is based on Kiunguja, a dialect people speak in the town of Zanzibar. Still, there are multiple Swahili dialects, with some mutually unintelligible, including the following:

Ancient Dialects

Maho (2009) regards these as independent languages:

Kimwani from Kerimba Islands and Mozambique’s northern coast.

Chimwiini of the ethnic minority groups in Barawa town and nearby areas on Somalia’s southern coast.

Kibajuni of the Bajuni minority group along the coast, including the islands on the Kenya-Somali border and on Bajuni Islands (Lamu archipelago’s northern part) known as Kigunya and Kitikuu.

Sidi, found in Gujarat (obsolete)

Socotra Swahili (obsolete)

He divided the other dialects into two categories:

Lamu Swahili

- People on Lamu (Amu) island and neighbouring areas speak Kiamu.

- Kipate is the native dialect on Pate Island, taken to be nearest to the initial Kingozi dialect.

- Kingozi, an archaic dialect along the coast of the Indian Ocean from Lamu to Somalia, is occasionally applied in poetry. Usually considered the origin of Swahili.

Mombasa Swahili

- In Mombasa is Chijomvu, a proxy dialect

- Kimvita is Mombasa’s major dialect (also called “Mvita”, meaning “war”, to refer to the various wars to capture it), another major dialect apart from Kiunguja.

- In Mombasa is Kingare, a proxy dialect

People near Vanga, Pangani, Mafia Island, Dar es Salaam, and Rufiji speak Kimrima.

Kiunguja is a language in the city of Zanzibar including the environs of Unguja Island (Zanzibar), Kitumbatu (on Pemba) dialects are all over the island’s biggest part.

Mambrui, Malindi

Chwaka

Chichifundi is a language on Kenya’s southern coast.

On Kenya’s southern coast is Kivumba.

in Madagascar is Nosse Be

Pemba Swahili

- The native dialect on Pemba Island is Kipemba.

- Kimakunduchi and Kitumbatu are dialects in the countryside of Zanzibar island. Kimakunduchi is the new name for “Kihadimu”; an ancient expression meaning “serf” and is taken to be pejorative.

- Mafia, Mbwera

- Makunduchi

- Kilwa (obsolete)

- Kimgao was formerly a language in the south and near Kilwa District.

Maho has multiple Comorian dialects being the third group. Many other bodies consider Comorian as a language of the Sabaki language, different from Swahili.

Other Locations

An Afroasiatic language predominates in Somalia with a Swahili variant known as Chimwiini (or Chimbalazi) of the Bravanese on the Benadir coast. Kibajuni is also a Swahili dialect, the native language of the Bajuni ethnic group, who inhabit Bajuni Islands and parts of southern Kismayo.

About 22000 people in Oman are estimated to speak Swahili. Many are children and grandchildren of people who were repatriated when the Sultanate fell in Zanzibar.

Swahili Poets

- Shaaban ibn Robert -Tanzanian author, poet, and essayist (1909-1962)

- Euphrase Kezilahabi -Tanzanian potent, novelist, and scholar (1944-1920)

- Mathias E Mnyampala -Tanzanian lawyer, poet, and writer (1917-1969)

- Tumi Molekane- South African poet and rapper (b. 1981)

- Fadhy Mtanga -Tanzanian graphic designer, photographer, creative writer, (b. 1981)

- Christopher Mwashinga -Tanzanian author (b. 1965)

Swahili Names

Swahili names are traditionally given to babies by their parents in East and Central Africa, particularly in countries like Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where Swahili is a widely spoken language. Swahili names are often derived from Arabic, Bantu, and other local languages.

Common Swahili boy names are Ahmed, Juma, Said, and Hassan. Common Swahili girl names are Fatima, Aisha, Salma, and Mwanaidi.

Swahili Sayings

There will be a pair of sayings with the same explanation about Where elephants fight, the grass is trampled:

Wapiganapo tembo nyasi huumia

When elephants fight, the grass is what gets damaged

Ndovu wawili wakisongana, ziumiazo ni nyika.

Grassland is what gets damanged, when a pair of elephants argue

Mwacha mila ni mtumwa.

The one who disregards his culture, is a slave.

Swahili Words

Check out these English Swahili:

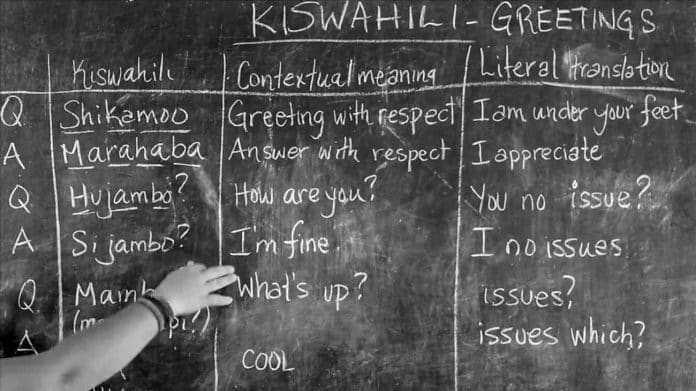

- hello in swahili is “habari”

- thank you in swahili is “Asante”

- freedom in swahili is “uhuru”

- good morning in swahili is “Habari za asubuhi”

- i love you in swahili is “nakupenda”

- swahili queen is “Malkia”

- swahili for good morning is “Habari za asubuhi”

Translate to Swahili

There are multiple Swahili translator websites and resources that you can use to translate between english and swahili.

From google translate swahili to alternative swahili translate sites. Here’s a list of all the resources you can use:

- google translate swahili to english

- swahili to english translator

- english to swahili translator

- swahili to english translation

- english to swahili translation

- translate english to swahili

- translate swahili to english

- swahili to zulu translation

- google translate english to swahili

Swahili in the US

The Swahili Village is a restaurant and cultural center. There are multiple locations in the US, including swahili village newark and swahili village washington.

The Swahili village bar & restaurant offers authentic East African cuisine, including dishes from Kenya, Tanzania, and other East African countries.

The Swahili Village in Washington DC is located in Beltsville, Maryland. Swahili village DC is decorated with traditional African artwork and furnishings, creating a vibrant and colorful ambiance. Swahili village beltsville also serves as a cultural center and event venue. The center hosts cultural events, such as African music performances, art exhibitions, and community gatherings.

Check out the swahili village – the consulate dc website!

FAQs

Where is Swahili spoken?

Swahili is primarily spoken in East and Central Africa. It is the official language of Tanzania and Kenya and is also spoken in Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, Mozambique, Somalia, Comoros, and Mayotte.

How do you say blessings in Swahili?

Blessing from english to swahili is “baraka”

Can you watch the BBC in Swahili?

Yes! Check out BBC Swahili here!

What is the Swahili beach resort?

The Swahili Beach Resort is a luxury beachfront resort located in Diani Beach, Kenya.

For more articles related to Tanzania Swahili language click here!