Zanzibar Revolution: Foreign Reaction and Legacy

Foreign reaction on Zanzibar revolution started when British troops in Kenya were informed of the January 12 coup at 4:45 am, and following a request from the Sultan they got ready within 15 minutes to carry out an attack on Zanzibar airport.

But, the British High Commissioner to Zanzibar, Timothy Crosthwait, didn’t report any occurrences of British expats being assaulted and therefore recommended against the intercession.

As a result, British troops in Kenya were delayed to four hours later. Crosthwait decided not to approve the immediate rescue of British citizens, as many held key government positions and their sudden removal would further disrupt the country’s economy and government.

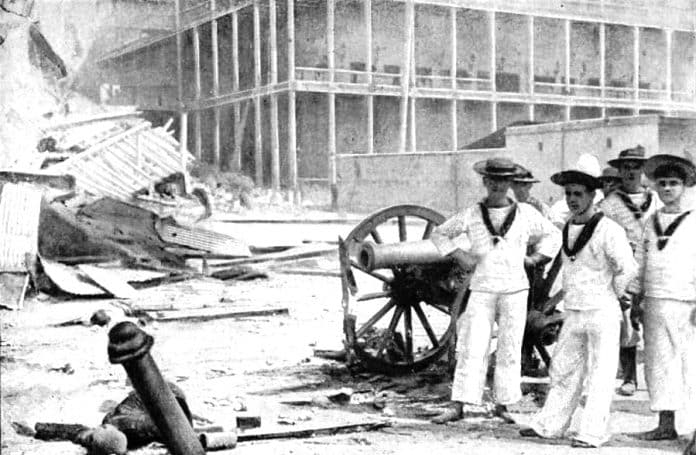

As the revolution continued, the US ambassador had approved the evacuation of U.S. citizens from the island, and the US Navy, USS Manley, arrived on January 13. The ship anchored in the port of Zanzibar City, but the United States did not get the approval of the Revolutionary Council to evacuate the civilians, so the ship was confronted by a group of armed men. Permission was finally granted on January 15, but the British considered the confrontation to be due to evil intentions against the Western regime in Zanzibar.

Speculations and Concerns

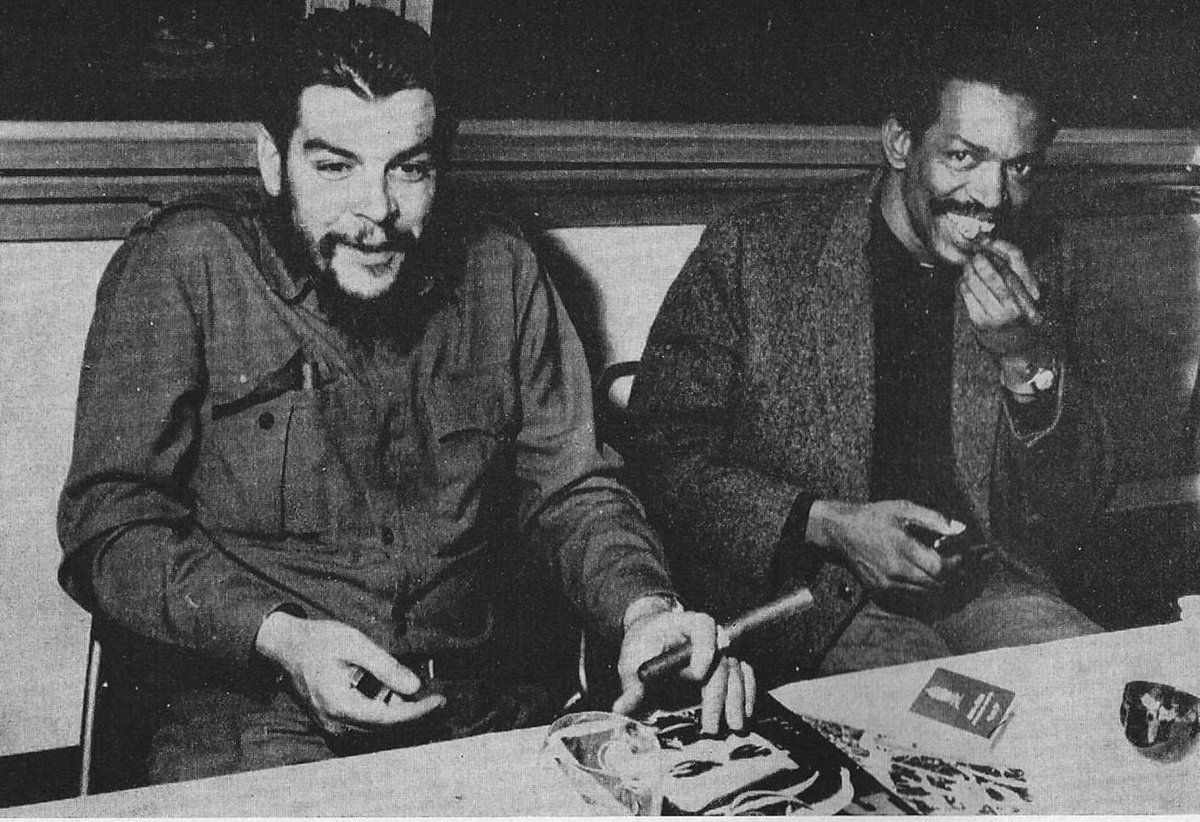

Western intelligence agencies believed that the coup was orchestrated by communists who distributed arms from the Eastern European Union. These allegations were reinforced by the appointment of Babu as Foreign Minister and Abdullah Kassim Hanga as Prime Minister, both of whom are known to be left-wing communists. Britain believed that the two were close allies of Oscar Kambona, Tanganyika‘s foreign minister, and that former Tanganyika army troops had been deployed to support the coup. Some members of the Umma Party wore Cuban army uniforms with Fidel Castro style beards, which was considered a sign of Cuban support for the coup. However, the practice was introduced by members of the ZNP branch office in Cuba, and it was common for members of the opposition to wear the uniform for several months before the coup. The new recognition of the Zanzibar government by the German Democratic Republic (the first African government to do so) and that of North Korea was further proof to the Western Government that Zanzibar was keeping itself close to the Communists. Just six days after the coup, the New York Times reported that Zanzibar was “on the brink of becoming a Cuba for Africa”, but on January 26

it denied any active communist involvement. Zanzibar continued to receive support from communist countries and by February it was known to receive advisors from the Soviet Union, GDR and China. Cuba also provided support when Che Guevara spoke on August 15 that “Zanzibar is our friend and we gave them our little support, our fraternal support, our revolutionary support at the right time” but denied the presence of Cuban forces during the coup. At the same time, western influence was declining and by July 1964 only one Englishman, a Dentist, remained in Zanzibar government employment. It is alleged that Israeli spy David Kimche was behind the coup, while Kimche was in Zanzibar on the day of the coup.

The ousted Sultan requested foreign reaction in terms of military assistance from Kenya and Tanganyika but was unsuccessful, although Tanganyika sent 100 militants to Zanzibar to calm down the unrest. Unlike the Tanganyika Rifles (formerly known as King’s African Rifles), the police were the only armed force in Tanganyika, and on January 20 the absence of the police caused the entire Armed Forces to revolt. This was due to dissatisfaction with the low pay levels and due to the untimely exchange of titles between British officers and Africans, the rebel insurgency sparked similar protests in Uganda and Kenya. However, the African continent’s order was restored quickly without the use of the British Army and Commandos.

The possibility of the emergence of an African communist government remained a source of concern in the West. In February, the British Foreign Affairs and Foreign Policy Committee stated that, while Britain’s trade interests in Zanzibar were “minute” and the revolution itself was “not necessary”, the possibility of intervention must be maintained. The committee was concerned that Zanzibar could be a center for promoting communism in Africa, just as Cuba was in the United States. Britain, and a large part of the Commonwealth, and the United States withdrew the recognition of the new regime until February 23, when it was already recognized by the communist countries. In Crosthwait’s view, this contributed to Zanzibar’s alliance with the Soviet Union; Crosthwait and his staff were deported on February 20 and were only allowed to return as soon as the agreement was reached.

British Military Intervention

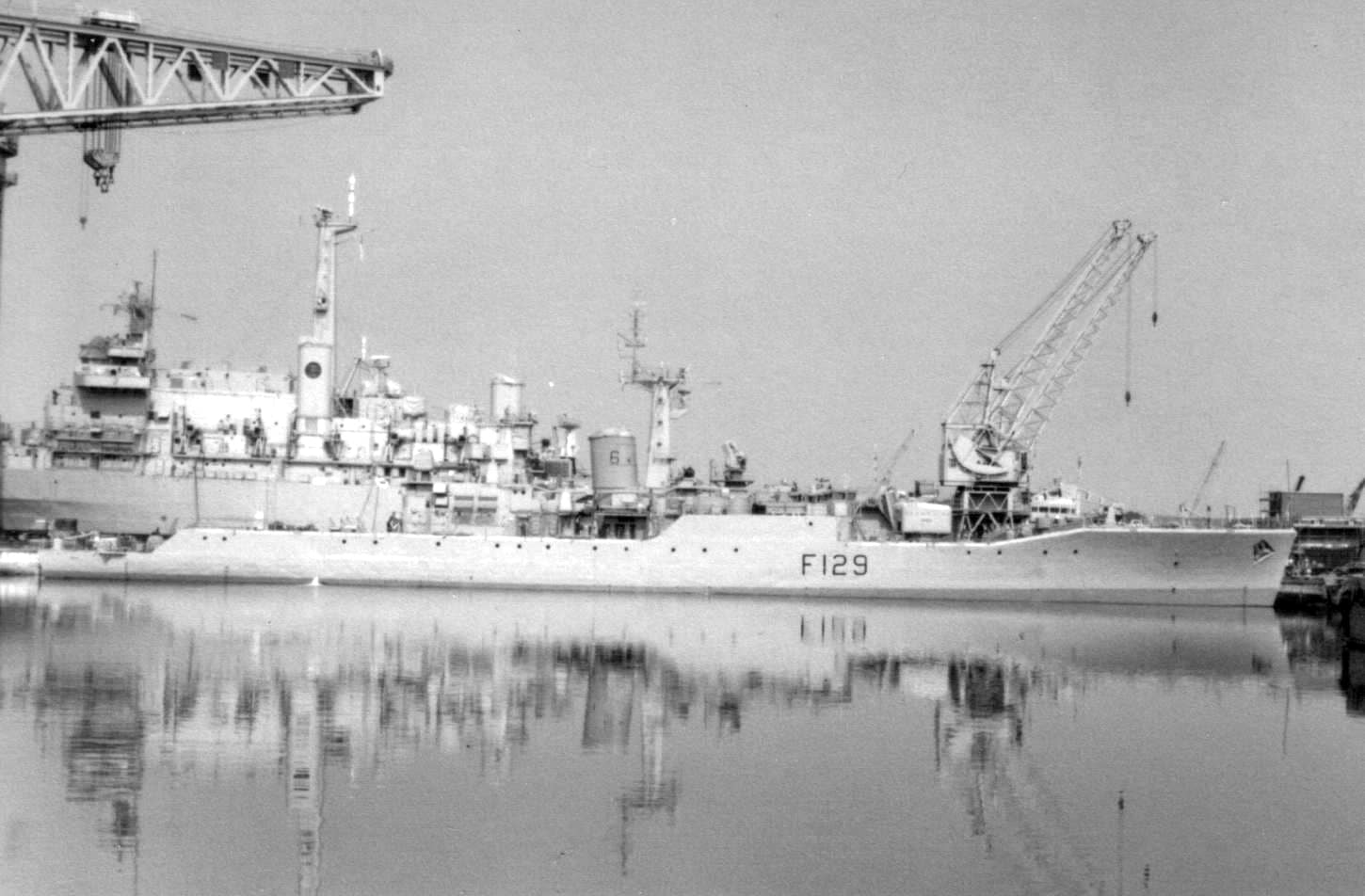

Following the removal of its citizens on January 13, the US government stated that it recognized that Zanzibar was placed within the British sphere of influence, and did not see a need of any other foreign reaction especially on their side. The United States did so, however, urging Britain to work with other Southeast African countries to quell unrest. The first British military vessel at the scene was a reconnaissance ship

named HMS Owen, which was diverted from its Kenyan coast and arrived on the evening of January 12. Owen joined the Rhyl warship and the Hebe auxiliary military ship on January 15th. While Owen’s light weapon was able to show the revolutionaries the power of the British army in a small attack, Hebe and Rhyl were a different situation. Due to inaccurate reports that the situation in Zanzibar was deteriorating, Rhyl was carrying a group of soldiers from the first Staffordshire unit from Kenya, a loading that was widely reported in the Kenyan media, and would block British-Zanzibar talks. Hebe had just finished removing stores from a naval base in Mombasa while loading weapons and explosives. Although the Revolutionary Council did not know the contents of the cargo loaded with Hebe, the Royal Navy’s refusal to allow the ship’s search led to suspicion on the beach and rumors circulating that it was an amphibious assault ship.

The rescue of a section of British civilians was completed on January 17, when military unrest in southeastern Africa led to the turning of the Rhyl ship to Tanganyika so that the deployed troops could help end the insurgency. In exchange, Gordon Highlanders’ army had been loaded into Owen’s ship so that intervention could be carried out if necessary. The Centaur and Victorious ships carrying planes were also transferred to the area as part of Operation Parthenon. Although it was never been done, Operation Parthenon was intended to be a warning if Okello or the hardliners of the Umma Party were trying to seize power from the moderate politicians of the ASP Party. In addition to the two ships, the plan involved three other ships, Owen, with 13 helicopters, 21 transport and reconnaissance aircraft, a second Scots Guard, 45 Commandos and one parachutes of the second parachutes. Unguja Island, with its airport, had to be captured as a result of a parachute and helicopter attack, followed by island control of Pemba. Operation Parthenon would be the largest sea and land attack carried out by Britain since the Suez Crisis.

Following the discovery that the revolutionaries may have received communist training, Operation Boris was the alternative to Operation Parthenon. This called for an attack on a parachute unit on the island of Unguja from Kenya, but was later abandoned due to poor security in Kenya and opposition to the Kenyan government over the use of its airport. Instead Operation Finery was organized, which would involve a helicopter attack by Commandos from HMS Bulwark, then a commanding ship set up a station in the Middle East. When Bulwark was out of the area, the launch of the Finery would require 14 days of preparation, so in the event an immediate response was necessary, the appropriate forces were put on alert 24 hours to launch a small operation to protect British civilians.

With the unification of Tanganyika and Zanzibar on 23 April, there was a concern that the Umma Party would carry out a coup; operation Shed was created to intervene if it occurred. The Shed would need batallions of soldiers, and surveillance vehicles, to be brought to the island and seize the Zanzibar airport and protect the Karume government. However, the risk of a coup over the alliance passed quickly, and on April 29 the forces prepared for Operation Shed were reduced to 24 hours alert. Operation Finery was canceled on the same day. Although concerns about a possible coup still existed, and on September 23, Operation Shed was amended by the Giralda Plan, which planed to involve the use of British troops from Aden and the Far East, if the Umma Party tried to overthrow President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania. A paramilitary force, a headquarters planning unit and some Commandos would be flown to Zanzibar to launch attacks from the sea, which were going to be backed by troops from British camps in Kenya or Aden to maintain law and order. Operation Giralda was withdrawn in December, ending Britain’s plans to invade the country militarily.

Legacy

One of the main consequences of the Zanzibar revolution was the overthrow of the Arab / Asian ruling class, whom held the power for nearly 200 years. Even though Zanzibar united with Tanganyika, Zanzibar continued to run a Revolutionary Council and House of Representatives which was, up to year 1992, which operated on a one-party system and had power over interior affairs. The local government was led by the President of Zanzibar, Karume being the first to serve the office. This government used the revolutionary success to implement reforms on the island. Many of them involved removing the Arabs from power. Zanzibar’s civil service, for example, became a completely African organization, and land was divided among Africans from Arabs. The revolutionary government also introduced social reforms such as free health care and opened up an education system for African students (who had occupied only 12 percent of high school positions before the revolution).

The government requested assistance from the Soviet Union, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), and the People‘s Republic of China to finance several projects and provide military advice. The failure of several GDR-led projects including the New Zanzibar Project, the 1968 urban restructuring plan to provide housing for all Zanzibaris, led Zanzibar to focus on Chinese aid. The Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar was accused of restricting personal freedom and traveling and using nepotism in the appointment of political and industrial offices, the new government of Tanzania did not have the capacity to intervene. Dissatisfaction with government operations was followed by Karume’s assassination on April 7, 1972, which was followed by weeks of clashes between pro-government forces and anti-government forces. The multi-party system was finally established in 1992, but Zanzibar remained plagued by allegations of corruption and vote fraud, although the 2010 general election appeared to be significantly improved.

The revolution itself is still an exciting event for Zanzibaris and intellectuals. Historians have classified the revolution as socially and ethnically diverse, with some claiming that African revolutionaries represented the working class rebels against the ruling classes and businessmen, represented by the Arabs and Southeast Asians. Some ignore this theory and present it as a racist revolution that was fueled by economic disparities between communities.

Within Zanzibar, the coup is an important cultural event, celebrated by the release of 545 prisoners on its tenth anniversary and by military parade on its 40th anniversary. Zanzibar Revolution Day has been designated as w public holiday by the Tanzanian government ; is celebrated on 12 January each year.

if you would like to find more articles about The People Republic of Zanzibar, click here!