The East African Campaign 1941 – Background, Fighting, Offensives and More

The East Africa campaign WW1 , which began in German East Africa (GEA) and stretched to parts of Portuguese Mozambique, British East Africa, Northern Rhodesia, Belgian Congo, and the Uganda Protectorate, was a series of guerrilla attacks and battles. In 1917 November, the Germans invaded Portuguese Mozambique and resumed the campaign in German East Africa while utilizing Portuguese supplies.

The German colonial troops, directed by Lieutenant Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (later “Generalmajor”), devised a strategy to divert Allied forces away from the Western Front and towards Africa. His tactics yielded mixed results as he was forced out of German East Africa in 1916. The East African campaign devoured a significant quantity of money and military supplies that could have been used on other fronts.

The Germans in East Africa fought throughout the war, getting notification of the ceasefire at 07:30 hours on November 14, 1918. The Germans formally surrendered on November 25, after both sides received confirmation. The GEA was divided into two League of Nations Class B Mandates: the United Kingdom’s Tanganyika Territory and Belgium’s Ruanda-Urundi, with the Kionga Triangle, granted to Portugal.

Background of the German East Africa Campaign

German East Africa

In 1885, the Germans colonized German East Africa (Deutsch-Ostafrika). The region stretched over 384,180 square miles (995,000 square kilometres) and included parts of modern-day Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi. The colony’s native population totalled 7.5 million people but was ruled by just 5,300 Europeans. Although the colonial rule was quite secure, the 1904–1905 Maji Maji Rebellion had just shaken the territory. A military Schutztruppe (“Protection force”) of 2,470 Africans and 260 Europeans, as well as 2,700 white settlers in the reservist Landsturm and a tiny paramilitary Gendarmerie, were available to the German colonial authorities.

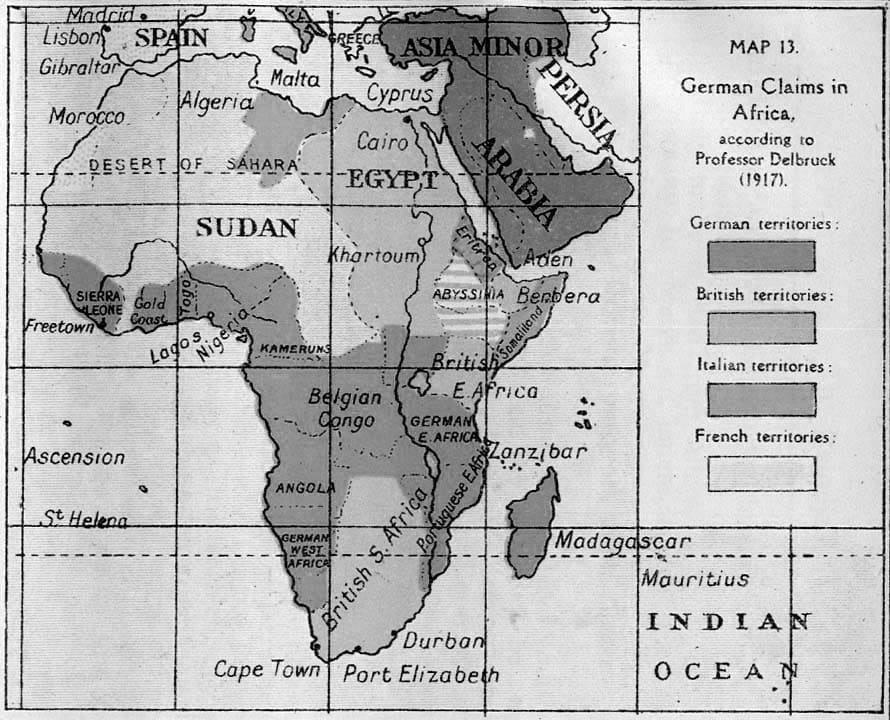

Following the onset of the WW I in Europe, German colonial expansion gained appeal, prompting the formation of a Deutsch-Mittelafrika (known as “German Central Africa”) to coincide with Europe’s resurgent German Empire. Mittelafrika practically included the acquisition of land, much of which was under the occupation of the Belgian Congo, so as to connect the Eastern, South-Western, and West African German colonies. The area would rule Central Africa, making Germany the continent’s most powerful colonial state by far. Despite this, the German colonial military force in Africa was ineffective, under-equipped, and scattered. Despite being better trained and experienced than their adversaries, many German soldiers during the East African campaign relied on antiquated black powder weaponry such as the Model 1871 rifle. At the same time, Allied forces were also dealing with similar issues of low numbers and inferior equipment; most colonial militaries were designed to act as local paramilitary police tasked with repressing resistance to colonial authority and were not prepared or organized to go to battle with foreign powers. Despite this, the German colonial empire’s biggest military concentration was found in East Africa.

German Strategy During the German East African Campaign

East African German forces under Lieutenant-Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, had the goal of diverting Allied supplies and forces away from Europe and towards Africa. Lettow wanted to draw British soldiers into East Africa by threatening the crucial British Uganda Railway, where he could engage them in a defensive battle. The German government devised a defense tactic for East Africa in 1912, in which the soldiers would retire to the hinterlands and wage a guerrilla war. The East African German colony posed a danger to Belgium’s neutral Congo. However, the Belgian government intended to maintain its African neutrality. The Force Publique was forced to enforce a defensive strategy until August 15, 1914, when German navy ships on Lake Tanganyika attacked Mokolobu port, followed by the Lukuga station a week later. Some Belgian administrators saw the conflict in East Africa as a chance to expand Belgian possessions in Africa; the seizure of Urundi and Ruanda would strengthen the De Broqueville government’s negotiating position to secure postwar restoration of Belgium. Jules Renkin, the colonial minister, attempted to barter Belgium’s increase in the territory in German East Africa for Portugal’s allocation in the northern part of Angola during the postwar Treaty of Versailles negotiations in order to provide a longer coast for the Belgian Congo.

The Initial Battle of the East African Campaign, 1914 to 1915

Early German Raids and the Outbreak

Against the intentions of the local commanders and metropolitan governments, the governors of the German and British East Africa favored a neutrality pact based on1885 the Congo Act to prevent war. The agreement produced some uncertainty during the early stages of the East African campaign war. The SMS Königsberg cruiser departed from Dar es Salaam on July 31st, implementing contingency preparations for operations against British trade. She narrowly escaped being sunk by cruisers from the Cape Squadron who had been dispatched to follow the ship and prepare to sink it. On August 5, 1914, Uganda protectorate forces attacked river outposts of the Germans near Lake Victoria.

That same day, the British War Cabinet approved the deployment of an Indian Expeditionary Force (IEF) to East Africa in order to eradicate raider bases. The HMS Astraea cruiser of the Royal Navy bombarded Dar es Salaam’s wireless station on August 8, then consented to a ceasefire provided that the town stayed an open city. This arrangement produced friction between Vorbeck and his nominal superior, Governor Heinrich Schnee, who resisted and later rejected the pact; it also resulted in the captain of Astraea being chastised for overstepping his authority. When the IEF tried to land in Tanga before the Battle of Tanga, the Royal Navy felt obligated to provide notice that they were breaking the agreement, deciding against surprise.

Despite the two governors’ limitations, the paramilitary and military forces in both of the colonies were mobilized in August 1914. In the East African campaign, the German Schutztruppe comprised 2476 Askaris and 260 Germans of all levels, which was the equivalent of two troops of the King’s African Rifles (KAR) in the East African colonies of the British. On the 7th of August, German forces stationed in Moshi were notified that the neutrality pact had expired and was instructed to raid over the border. Askaris in the Neu Moshi region launched their first offensive mission of the assault on August 15. On Kilimanjaro’s British side, Taveta fell to two Askari (300 men) companies, with the British only firing a token fire and retreating. On Lake Tanganyika, the Askari deployment stormed Belgian facilities in an attempt to destroy the steamship Commune and seize control of the lake. On August 24, German forces raided Portuguese outposts all across Rovuma, unclear of Portugal’s intentions because it had not become a British ally, causing a diplomatic problem that was only partially resolved.

The Germans continued raiding farther into British Uganda and Kenya in September. On Lake Victoria, German naval strength was restricted to Kingani and Hedwig von Wissman, a tugboat armed with a single pom-pom cannon that caused modest damage and a lot of noise. The Uganda Railway lake steamers SS Kavirondo, SS William Mackinnon, SS Sybil and SS Winifred were equipped as makeshift gunboats by the British; the tug was captured and destroyed by the Germans. Later on as the East African campaign progresses, the Germans raised Kingani, dismantled her cannon, utilized the tug for transport; and disarmed the tug and removed her “teeth.” Lake Victoria was now undisputedly under British command.

British Naval and Land Offensive During the East African Campaign

The British designed a two-pronged assault strategy during the East African campaign to end the raiding problem and captured the northern portion of the German colony. On November 2, 1914, an amphibious operation by the IEF “B” composed of 8,000 men in 2 brigades was to take place in Tanga to conquer the city and take control of the Usambara Railway‘s Indian Ocean terminal. On November 3, 1914, IEF “C” with 4,000 soldiers per brigade will move from the East African British colony of Neu-Moshi to the railroad’s western terminus in the Kilimanjaro region. Following Tanga’s capture, IEF “B” would march northwest quickly, join up with IEF “C,” and clean up the remaining German troops. Despite being outmanned 8:1 and 4:1 at Tanga and Longido, Vorbeck’s Schutztruppe won. In the East Africa chapter of the British official history of 1941, Charles Hordern defined the occurrence as being among” the most significant disasters in British military history“.

In the East African battle, just two British regiments took part. The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, Second Battalion, landed in Tanga with the Indian Army invasion force and stayed on the British-German East African frontier after that. The Royal Fusiliers’ 25th (Frontiersmen) Battalion was created in early 1915 for action in East Africa and remained there throughout the war. Furthermore, Rhodesia sent white contingents in 1914-15, including the 2nd Rhodesia Regiment, Nyasaland, and South Africa, which included the South African Expeditionary Force, which landed in February 1916.

The Imperial German Navy’s Königsberg as part of the East African campaign was in the Indian Ocean at the time of the war declaration. Königsberg sank the obsolete protected HMS Pegasus cruiser in Zanzibar harbour and then retreated into the River Rufiji delta during the Battle of Zanzibar. 2 shallow-draught monitors with six inches (150 millimetres) guns were transported from Britain and wrecked the cruiser on July 11 1915 after being trapped by British Cape Squadron warships, including an outdated pre-dreadnought warship. The Britons salvaged and utilized 6 four inches (100 millimetres) guns from Pegasus, later known as Peggy guns; the Schutztruppe took over Königsberg’s crew and the 4.1 inches (100 millimetres) main battery guns and used them until the conclusion of the war.

Expedition to Lake Tanganyika

During the East African campaign, Germans had controlled Lake Tanganyika since the war broke out with 3 armed steamers and 2 motorboats (unarmed). Toutou and HMS Mimi, each armed with a 3-pounder and a Maxim cannon, were hauled 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometres) by land to the British coast of Lake Tanganyika in 1915. On the 26th of December, they seized the German cruiser Kingani, renamed it HMS Fifi, then assaulted and sank the German cruiser Hedwig von Wissmann with 2 Belgian ships under the leadership of Commander Spicer-Simson Geoffrey. The Graf von Götzen and the unarmed motorboat Wami were the only German ships that remained at the lake. In February of 1916, the crew of the Wami intercepted the ship and ran her ashore, where it was burnt. Lettow-Königsberg Vorbeck’s gun was then dismantled and brought to the main combat front via train. The ship was scuttled after a Belgian aircraft bombing campaign on Kigoma in mid-July, and before approaching Belgian colonial soldiers could take it; Wami was subsequently re-floated and utilized by the British.

1916–1917 Allied Offensives

Reinforcements from the British Empire, 1916

Horace Smith-Dorrien, a General, was given orders to locate and combat the Schutztruppe as the continuation of their East African campaign, but he developed pneumonia on the way to South Africa and was unable to assume command. General Jan Smuts was tasked with overcoming Lettow-Vorbeck in 1916. Smuts had a huge force (for the area) with 13,000 South African men, including Boers, Rhodesians and British, as well as 7,000 African and Indian troops, totalling 73,300 men. In Mozambique, there was a Belgian troop and a bigger but ineffectual group of armed Portuguese soldiers. Supplies were transported into the interior by a big Carrier Corps made up of African porters operating under British leadership. Despite the fact that the endeavor was allied, it was a British Empire operation in South Africa. Lettow-Vorbeck had likewise grown in strength during the previous year, and his forces now numbered 13,800 men.

Smuts launched attacks from several fronts, with the major attack coming from the North by British East Africa (Kenya), while considerable troops from the Belgian Congo moved in two columns from the west, crossing Lake Victoria aboard the ships SS Usoga and SS Rusinga of the British troops and reaching the Rift Valley. From the southeast, another force proceeded over Lake Nyasa (Malawi). All of these armies failed to conquer Lettow-Vorbeck, and they all became ill while marching. With minimal action, the ninth South African Infantry began in February with 1,135 soldiers and by October had been reduced to 116 healthy personnel. The Germans almost invariably retreated from bigger British army concentrations, and the German Central Railway from Dar es Salaam to Ujiji was completely under British control by September 1916.

With Lettow-Vorbeck limited to German East Africa’s southern reaches, Smuts began evacuating Rhodesian, South African and Indian forces, replacing them with Askari from the King’s African Rifles (KAR), which numbered 35,424 men by November of 1918. By the beginning of 1917 of the East African campaign, over half of the British Army at the theatre was comprised of Africans, and by the conclusion of the war, it was almost entirely made up of Africans. In 1917 January, Smuts departed the area to join the Imperial War Cabinet in London.

1916–17 Belgian Offensives

Towards the end of 1915 and the start of 1916, the British recruited 120,000 carriers to transport Belgian equipment and supplies to Kivu (in the Belgian Congo’s east). The Congo’s communication lines required some 260,000 carriers, who were forbidden from going into German East Africa by the Belgian government, and Belgian troops were supposed to make a living from the land. The British established the Congo Carrier Section within the East India Transport Corps with 7,238 carriers that were conscripted from civilians in Uganda and taken to Mbarara for assembly in April 1916 to avoid plundering civilians, risk of famine and loss of food stocks, with most farmers already conscripted and relocated from their lands. The Force Publique, led by General Tombeur Charles, Colonel Molitor Philippe, and Colonel Frederik-Valdemar Olsen, began its East African campaign on April 18, 1916, and seized Rwanda’s Kigali on May 6, 1916.

German Askaris in Burundi were forced to flee due to the Force Publique’s numerical advantage, and Rwanda and Burundi were overrun by the 17th of June. After that, the British Lake Force and the Force Publique launched an assault on Tabora, the administrative capital of central German East Africa. Three columns occupied Biharamuro, Ujiji, Mwanza, Kigoma. The Germans were beaten and the settlement captured during the Battle of Tabora on September 19th. Despite the fact that 1,191 carriers perished or were thought dead during the march, Carbel suffered a 1:7 loss rate. Smuts instructed their soldiers to withdraw to the Congo, leaving them only occupying Burundi and Rwanda, to preclude Belgian claims to German territory in an after-war settlement. In 1917, the British were forced to recall Belgian troops, and the two allies planned their East African campaign together.

1917 British Attack

The East African campaign was taken over by Major-General Arthur Hoskins (KAR), previously the first East Africa Division’s commander. He was succeeded by South African Major-General Jacob van Deventer after 4 months of reorganizing communication connections. Deventer launched an attack in July of 1917, pushing the Germans 100 miles (160 kilometres) south by early fall. Lettow-Vorbeck engaged in a costly fight at Mahiwa from the 15th to the 19th of October 1917, with 2,700 British losses and 519 German victims in the Nigerian brigade. Lettow-Vorbeck was elevated to Generalmajor once word of the war reached Germany.

1917–18 German Offensives During the East African Campaign

Mozambique, Portuguese

As witnessed by an African artist, Lettow surrendered his soldiers at Abercorn, and on November 23, Lettow-Vorbeck crossed into Portuguese Mozambique to loot supplies from Portuguese camps. During the march, Lettow-Vorbeck split his army into three parts; a 1,000 men detachment led by Hauptmann Tafel Theodor ran out of ammunition and food and had to surrender before they reached Mozambique. Tafel and Lettow had no idea they were only a day apart on the march. After routing the Portuguese garrison at the Battle of Ngomano, the Germans marched into Mozambique for nine months in caravans of men, carriers, children and wives, but could not acquire much strength. The Schutztruppe scored a number of significant successes in Mozambique, allowing it to continue its East African campaign operations, but it also came dangerously near to being destroyed in the Battles of Lioma and Pere Hills.

Northern Rhodesia

In August of 1918, the Germans went back to German East Africa and then crossed to Northern Rhodesia. The German Army captured Kasama, which the British had evacuated, on November 13, 2 days after the Armistice was signed in France. Lettow-Vorbeck was delivered a telegraph reporting the signing of the armistice the next day near the Chambezi River, and he consented to a cease-fire. On November 25, 1918, Lettow-Vorbeck marched his men to Abercorn and publicly surrendered. As per 2007 costs, the East African campaign did cost Britain over £12 billion.

Aftermath of the East African Campaign

Analysis

The East African campaign involved about 400,000 Allied troops, sailors, builders, merchant marine crews, support workers and bureaucrats. 600,000 African carriers supported them in the field. In their failed pursuit of Lettow-Vorbeck and his little force, the Allies used roughly a million personnel. Lettow-Vorbeck had been cut off and had no chance of winning. His goal was to distract as many British forces to his chase for as long as possible, forcing the British to invest the most resources in soldiers, supplies and vessels against him. He was able to divert no more Allied personnel from the European theatre after 1916, despite turning over 200,000 South African and Indian troops against his army and garrisoning German East Africa in his wake. While some tonnage was moved to the African theatre, it was not enough to cause the Allied warships serious difficulty.

The Economy and Society

The East African campaign resulted in a surge in British East African exports and a rise in the political power of the white Kenyans. The economy of Kenya was declining in 1914, but exports increased from £3.35 to £5.9 million in 1916, thanks to emergency legislation that gave white colonists power over black-owned property in 1915. Tea and raw cotton were the main contributors to the rise in export value. By 1919, white ownership of the economy had risen from 14% to 70%.

The Nyasaland campaign and recruitment helped to spark the Chilembwe insurrection in January 1915, led by John Chilembwe, a baptist minister who was American-educated. Grievances against the system used by the colonialists, including racial discrimination and forced labour, drove Chilembwe. The insurrection began on the evening of January 23, 1915, when rebels headed by Chilembwe assaulted and murdered 3 white colonists at the A. L. Bruce Plantation’s headquarters in Magomero. During the night, an attempt on a Blantyre armoury was foiled. The colonial government had mobilized the colonial military and deployed regular military forces from the KAR by the morning of January 24. Following an unsuccessful government offensive on Mbombwe on January 25, the rebels attacked and burnt down a Christian mission in Nguludi. Mbombwe was easily retaken by government forces on January 26. Most rebels fled to Portuguese Mozambique, notably Chilembwe, but the majority were apprehended. In the aftermath, some forty rebels were sentenced to death and other 300 were incarcerated; Chilembwe was shot and killed by police patrol close to the border on February 3rd. Despite the fact that the insurrection was short-lived, it is often regarded as a watershed moment in Malawian history.

The East African Campaign World War I Casualties

Hew Strachan estimated that 3,443 British soldiers were killed in East African campaign, 6,558 died of sickness, and 90,000 African porters perished in the East African war in 2001. Paice reported over 22,000 British victims in the East African battle in 2007, with 11,189 of them dying, accounting for 9% of the 126,972 personnel involved. By 1917, around 1,000,000 Africans had been conscripted as carriers, depopulating numerous regions and killing approximately 95,000 porters, including 20% of East Africa’s Carrier Corps. Kenyan porters accounted for 45,000 of the dead or 13% of the male population. The battle cost the UK £70 million, which was close to the 1914 war expenditure. The East African battle had not become a scandal, according to a Colonial Office officer, “…because the individuals who suffered the most were carriers – and no one cared about native carriers” The 5,000 Belgian casualties include 2,620 men killed in battle or killed by sickness, but does include 15,650 porters. In Africa, 5,533 men were killed, 5,640 men were missing or taken, and an unknown but considerable number were injured.

There were no East African campaign records kept in German colonies of the number of people conscripted or killed, but Ludwig Boell (1951) wrote in Der Weltkrieg, German official history, “…of the loss of carriers, boys(sic) and levies, [we could] not take counts due to the lack of extensive sickness records.” Paice cited a 1989 approximation of 350,000 casualties and a 1:7 fatality rate. Carriers were seldom paid, and civilians’ cattle and food were requisitioned; a famine in 1917 caused by food scarcity and low rainfall killed another 300,000 civilians in German East Africa. Poor rainfall in 1917–1918, along with farm labour conscription in British East Africa, resulted in hunger, and the flu pandemic of 1918 reached Sub-Saharan Africa in September. Famine and illness killed 160,000 to 200,000 people in Uganda and Kenya, 250,000 to 350,000 in South Africa, and 10 to 20 % of the population in German East Africa; the flu epidemic killed 1.5 million to 2.0 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa.

For more articles about Tanganyika click here!