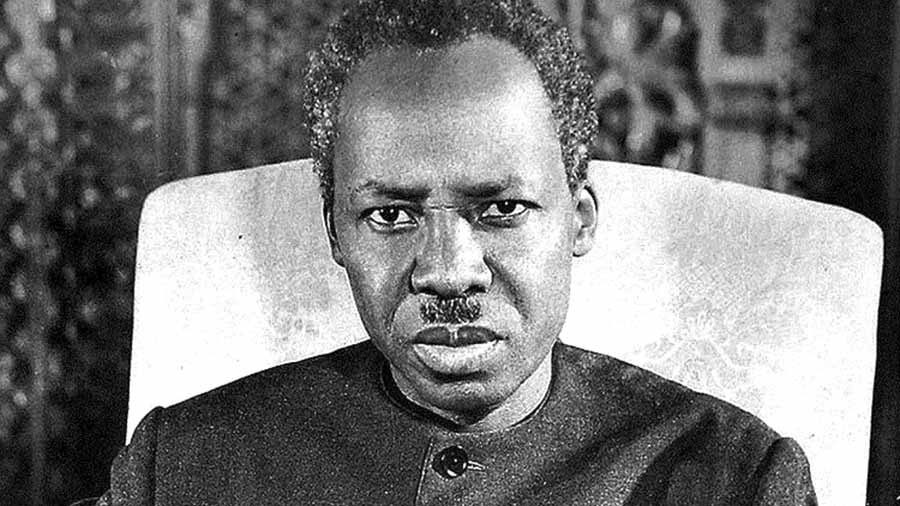

Julius Nyerere Hydropower Station (Stiegler Gorge Dam) – History, Location, Contract, Impacts and More

There is currently a power station under construction throughout the Rufiji River in eastern Tanzania called the JNHS [ Julius Nyerere Hydropower Station ], Stiegler Gorge Dam, or Rufiji Hydroelectric Power Project. Despite criticism, the plans for the power station were approved by the government in 2018. 2,115 MW (2,836,000 horsepower) are expected to be installed at the power station, and 5,920 Gigawatts of power will be generated annually. The government-owned TANESCO [Tanzania Electric Supply Company] will manage the project, including the power station and the Dam. Construction began in January 2019 and is scheduled to be completed by 2022.

Overview of the Stiegler Gorge Dam

Since the 1960s, the Tanzanian government has considered building this power plant, Julius Nyerere Hydropower Station. The Stiegler’s Gorge dam will become the 9th-largest in the world, the 4th-largest in Africa, and the biggest in East Africa when it is completed. For the 100 kilometers (62 miles) long, 1,200 square kilometers (460 square miles) wide, the 134 M [440 feet] curved concrete reservoir is expected to generate a reservoir lake with 34,000,000,000 cubic meters of water. The government-owned TANESCO [Tanzania Electric Supply Company] will be in charge of the project, which includes the power station and the Dam, as well as its management. The power plant is expected to generate 5,920Gigawatts of electricity per year.

History of the Stiegler’s Gorge Project Tanzania

A German engineer, Stiegler led the first mission to Stiegler Gorge in 1901 to assess potential infrastructure. In 1907, while measuring the gorge, Stiegler was attacked and killed by a wild elephant near the canyon. In his honor, the area was named after him. During the British occupation of Tanganyika, plans for a unique dam were created. Between 1928–1929, Alexander Telford performed Rufiji’s 1st systematic development research, followed by additional studies from engineer C. Gilman between 1938–1940. Irrigation infrastructure with just a tiny reservoir at Stiegler Gorge was envisioned in these studies mainly to decrease flooding and safeguard downstream infrastructures.

When the FAO [Food and Agriculture Organization] began studying the Rufiji River’s infrastructure in the 1950s, this study changed everyone’s perspectives. This included a much larger dam wall, measuring around 100 meters (330 feet), with the goal of transforming the valley into an artificial environment and providing irrigation water. In 1961, the FAO published a report that proposed irrigation on 200,000 ha of land [490,000 acres.

Following Tanganyika’s liberation in 1961, the focus shifted to hydropower. President Nyerere envisioned hydropower dams as critical components of his ambitious modernization plan. From the Second 5-year Development Plan (1969-1974), the focus of this modernization plan shifted to industrialization, necessitating the use of low-cost electricity. The Great Ruaha Hydroelectric power Project, which included hydro -plants in Mtera and Kidatu, was driven by this knowledge of the construction of dams as a developmental tool and their ability to supply cheap electricity to the entire nation. The Ruaha is an upriver headwater of the Rufiji.

The Stiegler’s Gorge Tanzania initiative has moved forward with the help of three major donors. It was supported by the Japanese External Trade Organization in the 1960s to conduct a feasibility analysis that proposed a 620 Megawatts plant. Meanwhile, the government of Nyerere enlisted the help of US agencies, notably the Bureau of Reclamation as well as the TVA [Tennessee Valley Authority]. A wide range of studies was conducted to plan for the transition of the Rufiji Canyon, which included industrialization, urban water supply, irrigation, and a massive fishery in the storage tank of the Dam. As a result of these studies, the RUBADA [Rufiji Basin Development Authority] was formed, with the primary goal of building the Dam and facilitating the more comprehensive enhancement and growth of the valley. Detailed viability and construction plans for Stiegler Gorge had been developed by the NORAD [Norwegian Development Agency] by the 1970s.

These plans, however, were never carried out. This is primarily due to the World Bank’s rejection of project financing. The Bank was a major funder of dams in third-world countries in the 1980s, especially in Tanzania, which was going through an economic crisis during this period. Given Tanzania’s limited growth in electricity demand, the World Bank doubted the need for a reservoir at Stiegler Gorge. Concerns about the project’s environmental impact grew, prompting Tanzania’s 1st Environmental Impact Assessment. The categorization of the Nyerere National Park, a.k.a Selous Game Reserve, wherein the gorge is located, as a World Heritage Site By UNESCO in 1982 heightened these concerns. In the 1990s,

Other international donors and the World Bank turned to the lesser and less-impactful Pangani and Kidatu Falls Dams.

However, plans for the reservoir were revived in 2006 by Jakaya Kikwete’s government. A time of sustainable economic growth followed after several years of the financial crisis between the 1980s and 1990s. The project’s revival was also prompted by Tanzania’s 2004-2006 power crisis, which resulted in nationwide load shedding. Members of the government in 2006 made it clear that the Stiegler’s Reservoir would be a top priority in order to take advantage of the nation’s growing economy. According to the Minister in Charge of Energy and Minerals, the Dam was included in the Power Sector Grand Plan drafted in 2009. In response, RUBADA, the agency in charge of implementing the Dam, began actively petitioning for the project in its entirety and meeting up with potential investors.

Several businesses have shown interest in working on the project. Like other power sector projects, the reservoir was scheduled to be constructed by the private sector supervised by Kikwete’s government. Private firms submitted unsolicited proposals for arrangements with the authorities to build the project. These arrangements, i.e., power purchase arrangements, would then be used to obtain funds and begin construction. In 2006–2008, Energen of Canada and Infrastructure Development Finance Ltd [IDF] of South Africa made the 1st such offer. Around the same time, Sinohydro is said to have made an offer.

The most prominent interaction, though, came from Brazil. Both countries decided to assist the construction of Stiegler Gorge Dam after negotiations between Tanzanian officials and Brazilian diplomats, including a visit by Brazilian Head of state Lula to Tanzania at the beginning of 2010. Between 2009 and 2012, there were several dialogues between the two nations. Odebrecht, a Brazilian firm, benefited from these dialogues. They agreed to build the hydropower station in 2012 after signing a Binding agreement with RUBADA. Odebrecht also conducted viability and design research and commissioned an assessment of the project’s environmental impact. However, Tanzanian participation in the project appeared to fade by 2014, ultimately delaying any construction work.

When President John Pombe Magufuli took office in 2015, this changed. He indicated in 2017 that the Stiegler Gorge Dam would be his government’s showpiece development project, funded by the government instead of being created by the private sector. In the autumn of 2017, the first round of bargaining for construction tenders was conducted. After this failed, a second-round was launched in the spring of 2018. The bid was won by Egyptian enterprises El Sewedy Electric and Arab Contractors. Magufuli has been outspoken in his condemnation of Dam’s critics, and one of his ministers, the minister of Interior, recently threatened opponents with jail time in a televised appearance.

Location of the Stiegler Gorge Dam

The Dam is being constructed alongside Stiegler Gorge, in the middle of Selous Game Reserve, Pwani District, some 220 kilometers [137 miles] southwest of Dar city, from across the Rufiji River.

The Selous Game Reserve, which covers 45,000 square kilometers [17,000 square miles], is one of the most significant global World Heritage Sites. The hydropower station and lake are expected to take up about 1,350 km² (520 square miles) within the game preservation site.

Contract

The Tanzanian government solicited proposals for the construction of the Stiegler Gorge Dam in August 2017. Within 36 months, the Dam should be completed by the chosen contractor. A new 400kV higher voltage line will be constructed to transport the generated electricity to a substation, where it’ll be incorporated into the national power system. The Tanzanian government receives advice from the Ethiopian government on this project’s implementation phase.

Despite the World Heritage Committee’s deep worry over Tanzania’s intention to proceed with the project, it was added to the reasons for the Nyerere National Park\ Selous Game Reserve to be placed on the World heritage list of endangered grounds, which previously exclusively addressed elephant trafficking and illegal hunting.

After diplomatic talks between Tanzanian Leader Magufuli and Egyptian Head of state Sisi, the Tanzanian government granted the Stiegler’s Gorge Hydroelectric Power Station’s construction and design contract to Arab Contractors and the Egyptian manufacturing Firm El Sewedy Electric in October 2018. At an estimated costs cost of $2.9 B [TSh6.558 trillion].

Tanzania’s government handed over the building site to the contractors in February 2019. Because mobilization of equipment took several months, actual work did not begin until June 2019. Tanzania’s government paid an initial investment of US$309.645M in April 2019, accounting for around 15% of the overall construction cost.

Redesign And Construction of the Stiegler Gorge Dam

2018 saw the unveiling of a revised design for the Stiegler Gorge Dam. The building of a dam wall with a height of 131 meters and a width of 700 meters is underway. The hydropower facility will generate estimated electricity of 2,115 MW. This Dam would surpass Egypt’s Aswan High Dam [2100 MW], Angola’s Lauca Dam [2069 mw], and Mozambique’s Cahora Bassa Dam [2075 mw] if completed on schedule by 2022.

A total of 2,115 MW is generated by the Dam, which is more than Tanzania’s current peak needed. In February 2017, the country’s highest-ever recorded electricity demand was 1051.27 MW. Between 1366.60 MW and 1,602 MW of installed power has been reported. Stiegler Gorge Hydroelectric Power Project will aid Tanzania’s industrialization and electricity generation efforts by increasing installed power on-grid.

Due to regular power outages, Tanzania’s government is pushing for new power generation. Power shortages in Tanzania are exacerbated by the summer months and less rainfall in specific years, hurting the country’s economy and social well-being. Load shedding, for example, is said to have cost Tanzania government between 5% and 7% of its GDP between 2014 and 2015.

Magufuli directed TANESCO to organize the site in advance of the start of construction. Some of the regions that received contracts were clearing the construction area, preparing a road for big trucks, and providing water and power. The government also granted logging rights to the large dam area, which could generate a lot of money.

EL Sewedy Electric, a privately owned Egyptian company, would be responsible for installing the generators, turbines, and transmission lines. At the same time, the Arab Contractors from Egypt will concentrate on the Civil engineering gig for the project. Tanesco, which the government owns, has signed a contract with them. There has been no official announcement of a funding package for the Dam, and the World Bank, as well as other financial institutions, have stated their opposition to the project. A $500 million loan from the African Import-Export Bank has been secured by El Sewedy, with promises from the CRDB Bank and the United Bank of Africa, which they intend to repay when the project materialized. In February of 2019, the Administrative authority will publicly hand over the work to the contractors after allocating a share of national finances to it in 2018.

The project was 40% completed by the beginning of June 2020. By January 2021, the Stiegler Gorge dam site’s bypass tunnel was operational, and digging of the 50-meter-deep dam foundation was underway. The 3 head-race tunnels, which will provide 9 penstocks for the 9 turbines, were in the process of being built. Each of the nine turbines will have a 235 Megawatts capacity. The base for the power plant was also being laid.

Construction Risks of the Stiegler Gorge Dam

The financial costs of the Stiegler Gorge Dam are being debated. In 2013, Odebrecht revised the Dam’s viability and design studies, estimating that this would cost a whooping £3.6 billion. This figure was used by the government to announce the new feasibility and design study in 2018. However, according to Hartmann, the underlying prices have drastically changed, such as the price of construction and concrete costs, as well as the cost of labor. By the start of June 2020, the project was 40percent complete. The Dam’s bypass corridor was operational by the beginning of January 2021, and the 50M-deep dam base was being dug. The construction of the 3 head-race corridors, which will provide 8-9 penstocks for the 9 blades, was underway. Each of the 9 blades will have a capability of 235 MW. The power plant’s foundation was also being set. Engineering services are available. Using recent dam examples, he estimates that the present cost estimate ought to be $7.57 billion after removing socio-environmental mitigation, rising to $9.8 billion if a reasonable amount of budget overruns is taken into account.

The selection of the two construction companies introduces additional risks. Dye claims that none of the two companies hadn’t any experience with dam construction and instead primarily built residential and commercial buildings and transmission systems, as seen in their public resume.

Given the inexperience of both companies, this is a huge surprise. Arab contractors were reportedly involved in the construction of the Aswan Dam in the early 1960s, but they would have been just one of many subcontractors on the Russian-controlled project. According to their website, the Firm has been working on building construction for the past ten years, but not on any power-generation or mechanical or large hydraulic projects. El Sewedy, on the other hand, appears to have primarily constructed transmission lines rather than complex electro-mechanical frameworks.

‘’ Barnaby Dye’’

This lack of expertise became noteworthy given Stiegler Gorge Dam’s sheer size and a high degree of hydrological fluid flow in the Rufiji River. There is no ‘owner’s engineer’ in place to oversee the construction process.

This contractual arrangement, as well as the appointed contractors, are fraught with dangers. Some are technical in nature, relating to developing a project that will live up and function (generating electricity) for the 50 years it’s expected to last. The accuracy and rigor of hydrology, climatic, sediment, and hydropower research, as well as the designers’ ability to properly implement intricate designs, will determine the live span of the project. With a workforce of over 4000 people, including several subcontractors, implementing infrastructural build-up of this scale would pose a construction management challenge. Neither Firm appears to have prior management experience on this scale. Most remarkably, this raises concerns about safety matters at the Dam, both during the construction period and afterward. A few numbers of Dam failures, like St. Francis Dam in the United States and the Malpasset Dam in France, were caused by inadequate studies and poor engineering guidelines and leadership.

Another concern is the potential impact on the environment and society. A lack of experience with mitigation standards of conduct means that the contractors are unlikely to know how to minimize their environmental impact, such as by not dumping dirt and waste into the river. Given the countless number of accidental deaths on Stiegler Gorge Dam projects prior to additional industry attempts in the twenty-first century, there are indeed concerns about the safety of employees on Dam projects.

In addition, the Nyerere National Park or Selous Game Reserve has been plagued by a longstanding problem of poaching. The main reason why the Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was placed on an endangered sites list was because of excessive poaching. Poaching and smuggling are more likely to occur in areas where there are more people, building projects, traffic, and logging camps sites because the companies don’t know how to impose anti-poaching laws and controls. Thus, the selection of contractors for the Stiegler Gorge project increases exponentially the already exiting problems in undertaking the project.

Risks to Operation

In order for the hydroelectric project to be successful, Stiegler Gorge Hydropower Project faces numerous risks. One of these is a result of global warming. Even if Tanzania experiences an increase in rain, studies show that the amount of precipitation is likely to be more variable. This is critical because it will have a negative impact on hydropower production, reducing the Dam’s ability to generate electricity. This is especially relevant in light of Tanzania’s reliance on hydropower. Hydropower is the primary source of Tanzania’s electricity. The country’s frequent power outages are primarily due to the failure of these dams during the dry season. If somehow the Stiegler Gorge Reservoir is completed, this vulnerability will continue to rise. Stiegler Gorge Hydroelectric Power would significantly decrease electricity production by 58.3 percent if it were brought online today.

Sedimentation is another danger. A study found that the reservoir was vulnerable to accelerated sedimentation. Since the Rufiji River is already clogged with sediment, the elevated levels of erosion expected around the reservoir are to blame for this. Due to increased sedimentation, the Stiegler Gorge Dam’s capacity to hold water would be reduced. A reduction in the reservoir’s capacity would make it utterly reliant on rainfalls, which would reduce its reliability.

TANESCO’s ability to sell the hydro-energy plants is also a financial risk for the Tanzanian government. It remains to be seen whether Tanzania will be able to sell the Dam’s energy given its current maximum capacity of 1.05 Gigawatts and installed capacity of about 1.5 Gigawatts. There have been a number of reports questioning the Tanzanian economy’s ability to handle the Dam’s demand. It will be difficult for the federal government to make a profit without these sales. As a result of these findings, it is unlikely that selling electricity generated by South and Eastern African Power Pools (SEAPP) to neighboring countries will be successful. There appears to be a deep skepticism among countries with regards to depending on others for electricity.

Stiegler Gorge Dam Negative Impacts

Experts and consultants have documented Stiegler Gorge Dam’s effects. They’ve argued that moving forward with the construction of Stiegler Gorge Dam comes with a significant price in terms of negative impacts on the environment and society as a whole.

Environmental Impacts

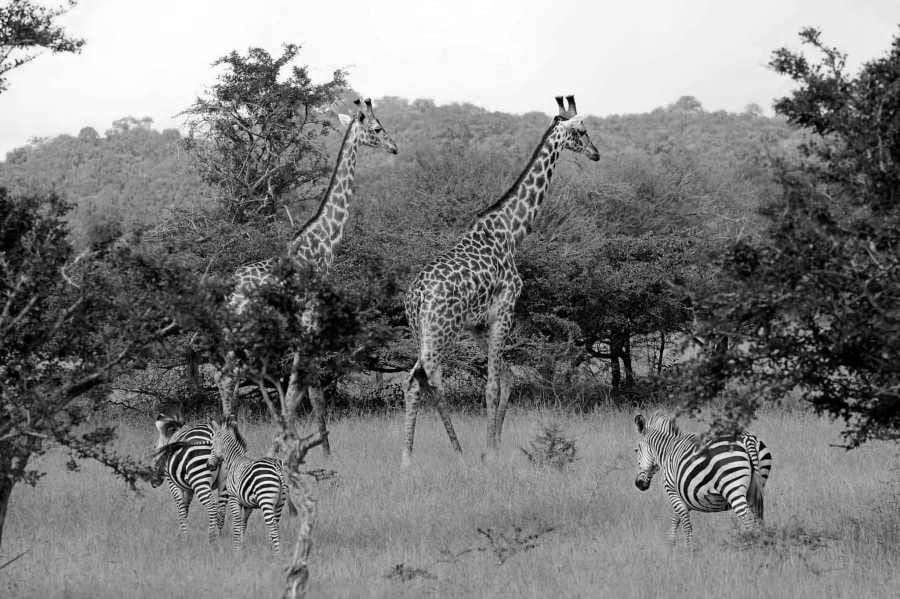

The environmental repercussions of Stiegler Gorge project are at the heart of the debate. The gorge’s location at the center of the Nyerere National Park\ Selous Game Reserve World Heritage Site raises apparent concerns. To begin with, the Dam will flood an area roughly equal to Andorra in terms of land area, reducing forest, riparian habitat, and swallowing over 2.2 percent of the total reserve area.

Furthermore, the Dam would be built directly above the Reserve’s most important biodiversity area. This area includes a marsh, a large wetland, and a savanna. The Rufiji River is an essential part of the environment’s creation.

This waterbody has a mighty hydrological surge during the rainy season. During the wet season, the Rufiji River’s route is altered by the force of water, resulting in a shifting sequence of dried river channels, oxbow lakes, and wetland. This results in a diverse habitat that goes against the surrounding drylands.

Seasonal variations are noticeable in the Rufiji River. It floods lots of land during the rainy season, hydrating the soil and helping to spread nutrient sediments. The Selous Reserve’s lakes are also refilled and connected during the rainy season.

The construction of a dam will alter the seasonal river sequence while also retaining sediment. It will result in a more consistent hydrological discharge, lowering the risk of flooding during the rainy season. This will jeopardize the river’s ecological irrigating as well as fertilizing functions. As a result, the Stiegler Gorge Reservoir will harm the Selous’ wetland areas and the diverse bird and animal life that uses them, including numerous herons, waders, and storks, as well as crocodiles and hippopotamus. Elephants and lions, among other large land mammals, reap the benefit of this water, especially during the summer season.

Black and white rhinoceros, Udzungwa red colobus monkey, cheetah, lesser kestrel, Sanje crested Mangaby, Rufous-winged partridge, wetland crane, Udzungwa forest partridge, and lions are among the Selous’ endangered species. According to impact assessment reports, these could be impacted by a future project.

The Stiegler Gorge Dam will cut off downstream oxbow lakes, causing them to become much more saline as a result of evaporation and shrinking in size. Fish stocks, mainly migratory fish, will not be able to regenerate if the lakes are cut off. These adverse effects would happen even with a prevention and mitigation flood discharge of 2,500centimeters, according to a survey by Duvail and Co. This suggested water release, for example, would put an end to at least one or two lakes located downstream.

The Rufiji River Delta is located underneath the Selous Game Reserve. The Ramsar Convention protects the delta area, along with Mafia Island, at the full international sphere of Wetland Protection. The seasonal nature of the river also influences the ecosystem of this region. The saline sea is countered by the rainy season’s river-water spike, maintaining a salinity balance within the delta that supports its existing animal and plant mix. This salinity balance supports the most extensive mangrove stands in EA[East Africa].

As a result of the river’s rainy season surge, an algal bloom within the ocean delta is supported by many fertile sediments. Fish populations increase rapidly as a result of this bloom, which causes a sharp rise in plankton. Other animals, including whale sharks, flock to the delta during the rainy season to enjoy the rich benefits of the bloom.

The Stiegler Gorge Dam will change the flow of the river and hold back sediment, which will harm the RAMSAR-Protected Delta Area, downstream lakes, and UNESCO Selous Site.

Social Impacts on Livelihoods

Environmental impacts will have significant socioeconomic consequences. The river’s yearly irrigating as well as fertilizing flood creates a fertile farmland area just below the park. Typically, this is used to support recession agriculture during the dry season. Undoubtedly, the Rufiji valley is home to some of Tanzania’s most fertile farmland, including vast paddy fields. Residents of the valley also use lakes that are recharged by yearly floods. These lakes serve as a source of irrigation as well as a valuable fish stock. As a result, any changes brought about by the reservoir will have a negative impact on people’s lifestyles downstream.

The Rufiji River fishing expedition has also had a significant impact. Tanzania’s most economically valuable fishery, centered on prawns, is located at the Selous.

The river’s rainy season pulse supports the numbers of prawns and other different fishes. As a result, the Stiegler Gorge Reservoir will harm fisheries in the Rufiji delta.

The Stiegler Gorge Dam will also have a significant impact on tourism. There will be two aspects to this. The portion of the Reserve directly below the gorge is the primary picture area at the Selous that most tourists enjoy taking pictures from there. Construction will have a negative impact on the rest of the park, which is used for hunting and tourism. Because of the enhanced roads and the large number of trucks transporting raw material to the Dam, the construction of the Dam will have a negative visual impact on the entire area. Transmission lines will be required for the hydropower plant. The Dam will be visually shielded by the Beho Beho Hills. Regardless, the park’s wildlife will be harmed in both the short and long term period, undermining the reason for target shooting and photo tourism.

Massive Rufiji floods, in particular, can cause significant damage to localities besides the Rufiji River. Floods in 1968, for example, wreaked havoc on crops, homes, and infrastructure. However, research shows that most people in the valley area value massive floods; they see them as a sign of blessing rather than a curse in the long run. This is due to the floods being viewed as agriculturally important. Floodwater spreads extra sediment, resulting in fertile agricultural situations in the years ahead.

From another angle, it is anticipated that the project will provide job opportunities as well as precious expertise to a large number of Tanzanian engineers.

For more articles related to Energy in Tanzania click here!