Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Biography – Everything You Need to Know

Who is Julius Nyerere?

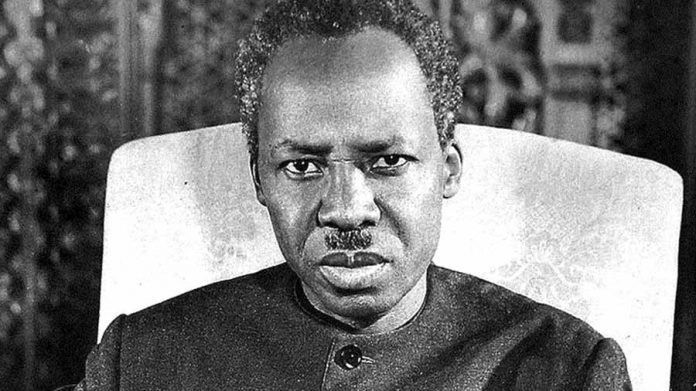

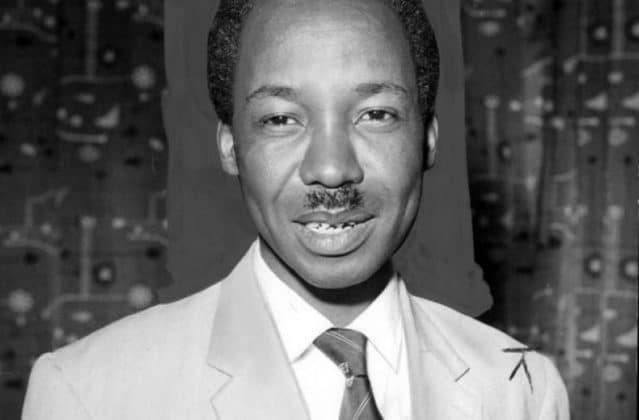

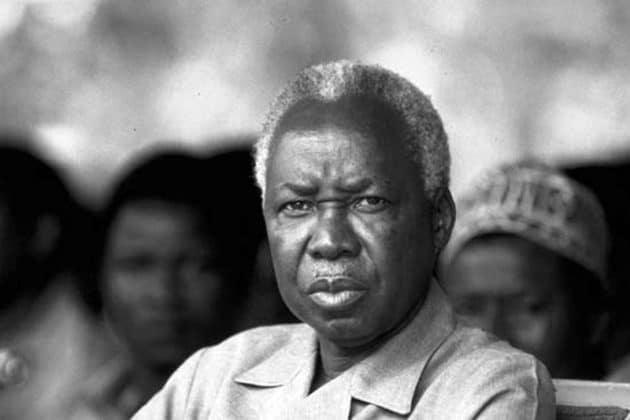

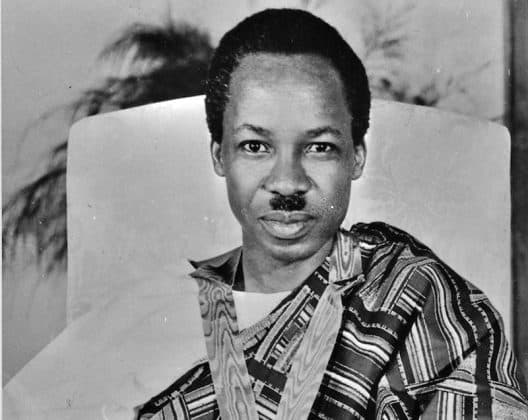

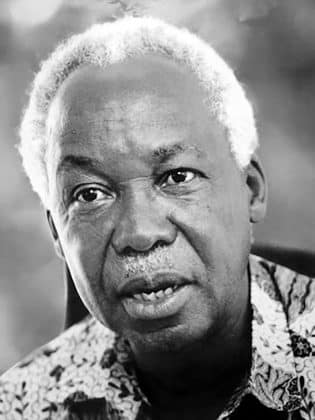

First President of Tanzania Julius Nyerere (also known as: Julius Kambarage Nyerere), who lived between April 13, 1922, and October 14, 1999, was a Tanzanian political theorist, politician, and anti-colonial activist. He ruled Tanganyika as Prime Minister between 1961 and 1962 and then as President between 1963 and 1964. He subsequently governed its successor country, Tanzania, as President from 1964 till 1985. Julius Nyerere was a founding member and chairman of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) and of its successor party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi, between 1954 and 1990. Ideologically, he was an African socialist and African nationalist who promoted a political idea known as Ujamaa.

Beginnings and Julius Nyerere Education and Career

He was born to a Zanaki chief in Butiama, which was then a part of the British colony of Tanganyika. After completing his education, he studied at Makerere College in Uganda before proceeding to study at Edinburgh University in Scotland. He returned to Tanganyika in 1952, got married and worked as a teacher. He helped establish TANU in 1954, with which he fought for the independence of Tanganyika from the British Empire. Mahatma Gandhi, an Indian independence leader, influenced him. Julius Nyerere advocated non-violent demonstrations to achieve its aim. He became a member of the Legislative Council in the 1958/1959 elections. He subsequently led TANU to victory at the 1960 general elections to become the Prime Minister. Talks with the British government resulted in the independence of Tanganyika in 1961. Tanganyika became a republic in 1962, with Julius Nyerere becoming its first president. His government sought the Africanization and the decolonisation of the civil service while encouraging harmony between indigenous Africans and the country’s European and Asian minorities. He encouraged the creation of a single-party system in Tanzania and failed in his mission to create a Pan-Africanist East African Federation with Kenya and Uganda. In 1963, the British assisted in suppressing a mutiny within the army.

In the aftermath of the Zanzibar Revolution of 1964, Tanganyika and Zanzibar unified to form Tanzania. Subsequently, Julius Nyerere placed an increasing emphasis on socialism and national self-reliance. Despite the fact that Julius Nyerere African socialism was different from the one promoted by Marxist-Leninists, Tanzania developed close ties with Mao Zedong’s Marxist-ruled China. Julius Nyerere announced the Arusha Declaration in 1967. In his arusha declaration of 1967 Julius Nyerere attempted to lay out his Ujamaa idea. Banks and other major companies and industries became nationalised; healthcare and education were expanded significantly. More importance was placed on agricultural development by creating communal farms, although these reforms hindered food production and left some places dependent on food aid. Julius Nyerere’s administration provided aid and training to anti-colonialist movements battling white-minority throughout southern Africa. He also oversaw the 1978-1979 war with Uganda. The war resulted in the ouster of Ugandan President Idi Amin. Julius Nyerere stood down in 1985, with Ali Hassan Mwinyi taking over. Mwinyi overturned many of Julius Nyerere’s policies. Julius Nyerere remained chairman of CCM until 1990, aiding the country’s transition to a multi-party system. He later served as a mediator in attempts to end the civil war in Burundi.

Julius Nyerere Ujamaa ideology and himself as a person made him a very controversial leader. His anti-colonialist stance gained him widespread respect across Africa. In power, he was praised for ensuring that Tanzania remained unified and stable in the decades after independence, unlike many of its neighbours. His development of a single-part state and the use of detention without prosecution led to allegations of dictatorial rule. He has also been criticised for mismanaging the economy. He is deeply respected within Tanzania, where he is usually referred to by the Kiswahili honorific Mwalimu, which means teacher. He is also described as the “Father of the Nation.”

History of Julius Nyerere

Julius Nyerere’s Early Life

Julius K Nyerere Childhood – 1922 to 1934

Julius Nyerere was born in Mwitongo, an area in the village of Butiama in the Mara Region of Tanganyika, on April 13, 1922. He was one of the 26 living offsprings of Burito Nyerere, the head of the Zanaki people. Burito was brought into this world in 1860 and named “Nyerere,” meaning caterpillar in the Zanaki language after an infestation of caterpillars overran the local neighbourhood when he was born. The German imperial administrators who governed the then German East Africa appointed Burito chief in 1915. The incoming British imperialists also endorsed his position. Julius Nyerere’s mum, Mugaya Nyang’ombe, was the fifth out of Burito’s 22 wives. Born in 1892, she married Burito when she was 15 years old in 1907. Mugaya had four daughters and four sons for Burito, of which Julius was the second child. Two of Julius’ siblings did not survive infancy.

The wives lived in several huts that surrounded Burito’s cattle enclosure, with his roundhouse located at the centre. The Zanakis were one of the smallest of the 120 ethnic groups in the British colony. The Zanakis are further divided into eight chiefdoms; they would only become united in the 1960s under the kingship of Burito’s halfbrother, Chief Wanzagi Nyerere. Nyerere belonged to the Abhakibhweege clan. Julius Nyerere was given the personal name Mugendi, meaning “Walker” at birth. However, the name was later changed to “Kambarage,” the name of a female rain spirit, on the advice of an omugabhu diviner. Julius Nyerere was raised in the Zanaki’s polytheistic faith system and lived in his mum’s house, helping in the farming of the maize, cassava and millet. He also participated in the herding of cattle and goats alongside other boys. He underwent the traditional Zanaki circumcision ritual at Gabizuryo at some point. Being the son of a chief, he had exposure to African-administered authority and power. Living in the compound made him appreciate communal living, which would later influence his future political ideas.

Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere Schooling: 1934 to 1942

The British colonial government supported the education of the sons of chiefs with the belief that it would help preserve the chieftain system and forestall the development of a distinct educated native elite who may question colonial rule. At Burito Nyerere’s prompting, Julius Nyerere started his education in February 1934 at the Native Administration School in Mwisenge, Musoma. The school was located 35 kilometres from his home. His education placed him in a favoured position because most of his mates at Butiama were unable to afford a primary education. His education was in Kiswahili, a language he had to master while in school. Julius Nyerere shone at the school, and after six months, his results were so good that he was allowed to skip one grade. He did not take part in sporting activities and preferred to spend his free time reading in the dormitory.

While at the school, he had his upper front teeth filed into triangular points in the tooth filing ritual of the Zanaki people. Perhaps, he took up smoking at this point, a habit that stuck with him for many decades. He also became curious about Roman Catholicism, although his initial concern was with discarding the veneration of his people’s native deities. To know more about Christianity, Julius Nyerere walked 14 miles with his school friend Mang’ombe Marwa to the Nyegina Mission Centre, operated by the White Fathers. Marwa eventually backed out while Julius Nyerere continued going. He finished elementary school in 1936. He had the best result in the entire Western Province and Lake Province region. A government scholarship given to him because of his academic excellence allowed him to attend the prestigious Tabora Government School, a secondary school in Tabora. While there, he also did not participate in sporting activities. However, he helped establish a Boy Scout’s brigade after studying Scouting for Boys. Many of his mates remembered him as competitive, ambitious and keen to top the class in examinations. With books he got from the school library, Julius Nyerere was able to immensely improve his understanding of the English language. He was an active member of the school’s debating society, and his teachers recommended him as head prefect. However, the headmaster vetoed the recommendation because he felt Julius Nyerere was “too kind” for the role. In line with Zanaki tradition, Julius Nyerere entered an arranged marriage with a young girl named Magori Watiha. At the time, Magori was only three or four years old but had been chosen for him by his father, though they continued to live separately. Julius Nyerere’s father died in March 1942 during his final year at Tabora. The school turned down his request to go home for the burial. Julius Nyerere’s brother, Edward W. Nyerere, was chosen as their father’s heir. Subsequently, Julius Nyerere chose to be baptized as a Roman Catholic. He took the name ‘Julius’ at his baptism. Nyerere would later go on to say that it was silly that Catholics need to take a new name other than their tribal name at baptism.

Makerere College in Uganda – 1942 to 1947

Julius Nyerere finished his secondary education in October 1941 and decided to continue his studies at Makerere College in the Ugandan capital of Kampala. He got a bursary to pay for a teacher training programme there. He arrived in Uganda in January 1942. While at Makerere, Julius Nyerere studied with many of the most brilliant students in East Africa. He spent less time socializing and dedicated most of his time to reading. The young Julius Nyerere took courses in Latin, Greek, biology and chemistry. Strengthening his Catholicism, he perused the Papal Encyclicals and also read the works of Catholic thinkers like Jacques Maritain; however, the works of the liberal British thinker John Stuart Mill influenced him the most. He entered a literary contest and applied Mill’s concepts to the Zanaki society in writing an essay about the oppression of women. The essay eventually won him the competition. Julius Nyerere also actively participated in the Makerere Debating Society and formed a chapter of Catholic Action at Makerere College.

He penned a letter to the Tanganyika Standard in 1943. In the letter, he discussed the current Second World War and contended that capitalism in Africa was an alien idea and that Africa should take up “African Socialism.” According to him, an African is a socialistic being by nature. He further went on to explain that the educated African should be at the forefront in moving the people towards a more definite socialist paradigm. Molony felt that the letter marked the onset of Julius Nyerere’s political maturity, mainly by understanding and advancing the beliefs of contemporary black thinkers. In 1943, Julius Nyerere teamed up with Hamza Kibwana Bakari Mwapachu and Andrew Tibandebage to create the Tanganyika African Welfare Association (TAWA) to help the small population of Tanganyikan students studying in the university. TAWA was allowed to die off, and Julius Nyerere brought the mostly moribund Makerere branch of the Tanganyika African Association (TAA) to life. By 1947, TAA had also stopped functioning. Despite being conversant with racial discrimination from the white colonial minority, he maintained that people be treated as individuals, observing that many white persons were not intolerant towards native Africans. Julius Nyerere finished from Makerere College with a diploma in education after three years.

Tanzania Julius Nyerere Early Teaching Years: 1947 to 1949

Julius Nyerere went back home to Zanaki after completing his studies at Makerere College. He built a house for his widowed mum and spent his time studying and farming in Butiama. He had teaching offers from both the mission-owned St. Mary’s and the state-owned Tabora Boys’ School. He chose the former despite offering lower pay. He participated in a public debate with two other teachers from Tabora Boys’ School, where he argued against the assertion that “The African has gained more than the European since Africa was partitioned.” He won the debate and was subsequently banned from returning to the school. When not in school, he gave free English lessons to older natives and lectures on political matters. He worked briefly for the government as a price inspector, going into shops to find out what they were charging. He eventually quit the job after the government overlooked his reports about phony prices. While in Tabora, Magori Watiha, the woman Julius Nyerere was arranged to marry, was sent to stay with him to pursue her elementary education there; he, however, forwarded her to stay with his mum. Instead, he started seeing Maria Gabriel, a school teacher at Nyegina Primary School in Musoma. Despite being a member of the Simbiti tribe, she was a devout catholic like Julius Nyerere. He proposed to marry her, and they became unofficially affianced at Christmas 1948.

His political activities became more intensified in Tabora. He joined the local chapter of the TAA and became its treasurer. The chapter opened a co-operative shop where they sold basic items like soap, flour, and sugar. He attended the association’s conference in Dar es Salaam in 1946. At the conference, the TAA formally declared its commitment to supporting the movement for Tanganyika’s independence. He worked with Tibandebage to rewrite TAA’s constitution. He used the group to organize resistance to Colonial Paper 210 in the area, believing that the voting reform aimed to give the white minority further privilege. Father Richard Walsh —an Irish priest who doubled as the director of St. Mary’s— urged Julius Nyerere to consider further education in the U.K. He convinced Julius Nyerere to sit for the University of London’s entrance examination. He took the examination and passed with a second division in January 1948. He sought funding from the Colonial Department and Welfare Scheme and was unsuccessful at first. In 1949, he tried again and got the needed funding. He reluctantly agreed to study overseas. His reluctance was borne out of the fact that he wouldn’t be able to cater for his siblings and mother any longer.

University of Edinburgh: 1949 to 1952

In April 1949, Julius Nyerere flew to Southampton, England, from Dar es Salaam. From London, he then journeyed by train to Edinburgh. When he got to the city, Julius Nyerere lodged in a building for “colonial people” in the suburb of Grange. He commenced his studies with a short course in physics and chemistry and passed Higher English in the Scottish Universities Preliminary Examination. In October 1949, he was granted admission to study for a Master of Arts degree at the Arts faculty of the University of Edinburgh. His programme was an Ordinary Degree of Master of Arts, which was considered the equivalent of a Bachelor of Arts in most English universities rather than a postgraduate degree associated with the term “Master of Arts.”

In 1949, apart from Julius Nyerere, there was only one other black student from British East Africa studying in Scotland. His first year of M.A. studies saw him offering courses in political economy, social anthropology, and English literature. Ralph Piddington taught him social anthropology. In political economy, he chose courses in British history and economic history, with Richard Pares teaching him the former. Julius Nyerere later called Pares a wise man who taught him a lot about the things that made the British tick. In his third year, he offered moral philosophy and a constitutional law course taught by Lawrence Saunders. Though his grades weren’t exceptional, he was still able to pass all his courses. He was described as a brilliant and active member of the class and the parties by his moral philosophy tutor.

Julius Nyerere made a lot of friends while living in Edinburgh and socialized with West Indians and Nigerians dwelling in the city. Julius Nyerere was never reported to have experienced racial prejudice during his stay in Scotland. However, it is possible that he encountered it; many black students studying in Britain at the time noted that white British students were mostly less discriminatory than other sections of the British population. In the classroom, he was mostly treated as equals with fellow white students. This equality boosted his self-belief and may have helped mould his faith in multi-racialism. While studying in Edinburgh, he may have taken up part-time work to support himself and his family in Tanganyika. He visited a Welsh farm alongside other students on a working holiday where they took part in potato picking. He travelled to London in 1951 to meet fellow Tanganyikan students. He attended the Festival of Britain during the visit. That same year, he co-authored a commentary for The Student magazine. In the article, he condemned plans to make Tanganyika a part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Julius Nyerere and co-author John Keto opined that the plan was aimed to advance white minority rule in the area. In February 1952, the World Church Group organised a meeting on the issue of the Federation, and Julius Nyerere was in attendance. Hastings Banda, a future Malawian leader and then medical student, was among the speakers at the event. Julius Nyerere finished from the University of Edinburgh with an Ordinary Degree of Master of Arts in July 1952. He left Edinburgh the same week and was granted a brief British Council Visitorship to inspect institutions of learning in England. He based himself in London during the visitorship.

What Changes Did Julius Nyerere Bring to Tanzania?

Political Activism – What is Julius Nyerere Famous For?

Establishing the Tanganyika African National Union: 1952 to 1955

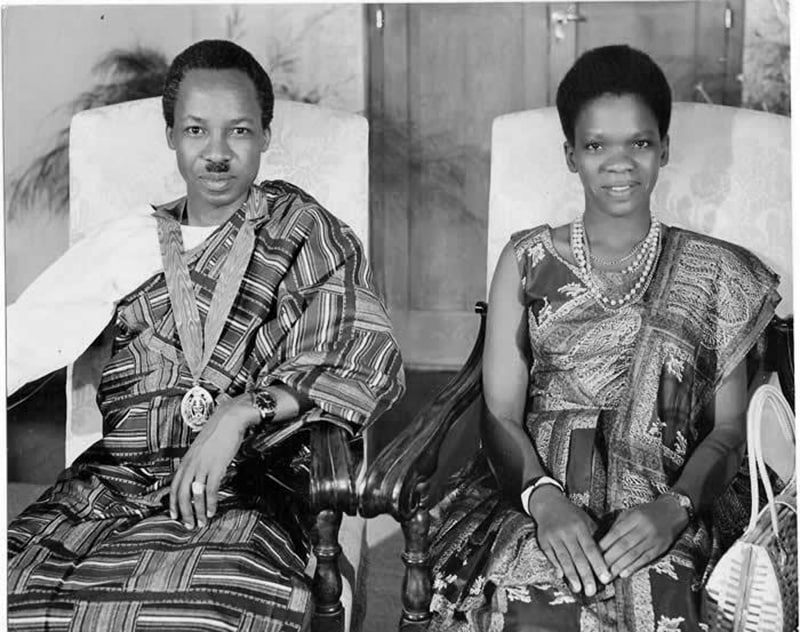

Julius Nyerere sailed to Dar es Salaam aboard the SS Kenya Castle, arriving in October 1952. He boarded a train to Mwanza and took a lake steamer to Musoma before finally arriving at Zanaki lands. He erected a mud-brick house for himself and his lover, Maria. They got married at Musoma mission on January 24, 1953. They soon relocated to Pugu, near Dar es Salaam, when Julius Nyerere was employed as a teacher of history at one of the best schools for native Africans in Tanganyika, St. Francis’ College. The couple’s first child, Andrew, was born in 1953. Julius Nyerere became more involved in politics, and in 1953 he was voted in as president of the TAA. His impressive rhetorical skills, coupled with the fact that he belonged to a minority tribe, aided his ascendancy to the position. Had he been a member of one of the larger tribes, he may have faced stronger opposition from members of rival ethnic groups. Under Julius Nyerere leadership style, the TAA became more involved in politics, committing itself to the actualization of Tanganyikan independence from the British. According to Bjerk, Julius Nyerere became prominent as a symbol of the flourishing movement for independence.

On July 7, 1954, with the help of Oscar Kambona, Julius Nyerere changed the TAA into a political party called the Tanganyikan African National Union (TANU). The three sons of Dossa Aziz, John Rupia and Kleist Sykes were among the early members of TANU. Rupia was an entrepreneur who was one of the richest Africans in the country at the time. He went on to serve as the party’s first treasurer and largely financed the group in its formative years. A temporary spot opened up in the legislative council when David Makwaia went to London to serve on the Royal Commission for Land and Population Problems. The governor of the colony subsequently appointed Julius Nyerere to fill the vacancy. In his maiden speech at the council, he hammered on the need to build more schools in the country. The government brought Makwaia back from London to make sure Julius Nyerere was removed when he declared that he would protest planned government policies to increase civil servants’ salaries.

At party meetings, Julius Nyerere maintained the need for Tanganyika to become independent. However, he insisted that an Africa-led independent government would not throw out the country’s Asian and European minorities. He was a great admirer of the Indian independence leader Mohandas Gandhi, popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi. He supported Gandhi’s approach to gaining independence by non-violent protest. Julius Nyerere’s activities were closely monitored by the colonial government, who were concerned that he could initiate a vicious anti-colonial insurrection like the Mau Mau uprising in nearby Kenya.

The United Nations sent a delegation to Tanganyika in August 1954. Subsequently, they published a report that recommended a 20 to 25-year timetable for the independence of the colony. The U.N. had planned to deliberate the issue further at a meeting of the trusteeship council in New York City. TANU sent Julius Nyerere as its representative at the meeting. At the request of the British government, the U.S. agreed to forbid Julius Nyerere from staying for longer than 24 hours before the meeting or going outside an eight-block radius of the headquarters of the United Nations. Julius Nyerere arrived in New York in March 1955 as part of a trip largely financed by Rupia. He told the trusteeship council that Tanganyika would be able to govern itself long before 20 to 25 years with the help of the trusteeship council and the British Administering Authority. At the time, the idea sounded highly ambitious to everybody.

Due to his pro-independence activities, the government pressed Julius Nyerere’s employer to fire him. Julius Nyerere left the school on his return from New York, partly because he didn’t want his continued employment to create problems for the missionaries. He returned to his Zanaki homestead with his wife in April 1955. He rejected job offers from an oil company and a newspaper. Instead, he took up the job of a tutor and translator for the Maryknoll Fathers, who were getting ready for a mission among the Zanaki people. TANU’s influence had grown throughout the country by the late 1950s. The party had gained large support that saw its membership grow from 100,000 in 1955 to 500,000 in 1957.

Touring Tanganyika: 1955 to 1958

In October 1955, Julius Nyerere went back to Dar es Salaam. From that time until Tanzania gained independence, he travelled around the country almost continuously, in TANU’s Land Rover. Edward Twining, the British colonial Governor of Tanganyika, did not like Julius Nyerere; he regarded Julius Nyerere as a racialist who wished to foist native domination over the South Asian and European minorities. Twining created the supposedly “multi-racial” United Tanganyika Party (UTP) to oppose TANU’s African nationalistic idea. Nevertheless, Julius Nyerere stated that their fight was against colonialism and not against white people. He made friends with white minority persons like Lady Marion Chesham, a United States of America-born widow of a British farmer. She acted as an intermediary between Twining’s government and TANU. In a 1958 editorial published in TANU’s newsletter Sauti ya Tanu, Julius Nyerere urged members of the party to shun violence. The editorial also condemned two district commissioners in the country, accusing the first of putting a chief on trial for fabricated reasons and the other for attempting to sabotage TANU. In response to the editorial, three counts of malicious defamation were filed by the government. The trial lasted close to three months. In the end, the judge found Julius Nyerere guilty and stipulated that he could either go to jail for six months or pay a fine of £150; he chose the latter.

Twinning declared that elections for a new parliamentary council would come up in early 1958. The elections would take place in ten constituencies, with each voting three council members: one European, one native African, and one South Asian. This pattern would stop the dominance of the European minority in political representation. However, it still meant the three racial blocs would be equally represented even though native Africans accounted for 98% of Tanganyika’s population. Due to the disproportionate representation, most of the leaders of TANU felt it should avoid the election. However, Julius Nyerere disagreed. He felt TANU should participate in the election and secure most of the African representative seats to boost their political influence. He argued that if they boycotted the election, the UTP would have a clean sweep, and TANU would have to function entirely outside of government, prolonging their independence struggle. At a conference in Tabora in January 1958, Julius Nyerere convinced TANU to participate. In the elections that took place between 1958 and 1959, the party won all the seats it contested. Julius Nyerere ran as TANU’s candidate against a non-affiliated candidate Patrick Kunambi, in the Eastern Province election. Kunambi amassed a paltry 800 votes to Julius Nyerere’s 2,600. A few of the elected Asian and European candidates were sympathetic to TANU’s cause. This made TANU the dominant party in the council.

TANU in Government: 1959 to 1961

In March 1959, Richard Turnbull, in his position as the new British Administrator of Tanganyika, offered TANU five out of the twelve ministerial positions available in the government. He was prepared to work out a violence-free transition to independence. Julius Nyerere visited Edinburgh in 1959. In 1960 he was present at a conference of Independent African countries held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. At the conference, he presented a paper that called for the creation of an East African Federation. He proposed that Tanganyika could stall its independence from the British until neighboring Uganda and Kenya could attain independence as well. He felt it would be easier for the three states to merge at the point of independence rather than after because, after independence, the respective governments might think they were losing their sovereignty via unification. Most of the senior members of TANU were against the idea of stalling Tanganyika’s independence; the party was growing and had more than a million members as of 1960.

In the general election held in August 1960, TANU secured 70 out of the 71 available seats. As the leader of TANU, Julius Nyerere was summoned to constitute a new government, becoming its chief minister. In that same year, British PM Harold Macmillan delivered his “Wind of Change” speech, signaling Britain’s willingness to take apart its empire in Africa. A constitutional convention took place in Dar es Salaam in March 1961 to decide the structure of an independent constitution; British officials and anti-colonial campaigners attended. Julius Nyerere conceded to the United Kingdom’s colonial secretary Ian Macleod’s request that Tanzania retains the British Queen Elizabeth II as the country’s head of state for one more year before transitioning into a republic. Tanganyika became self-governing in May. As PM, one of Julius Nyerere’s first actions was stopping the supply of labourers from Tanganyika to gold mines in South Africa. Although this move resulted in a yearly loss of close to £500,000 to Tanganyika, Julius Nyerere felt it was necessary to signify their disapproval of the apartheid regime of white-minority dominance and racial discrimination carried out in South Africa.

The Era of Ujamaa Julius Nyerere Presidency and Premiership of Tanganyika

Premiership of Tanganyika: 1961 to 1962

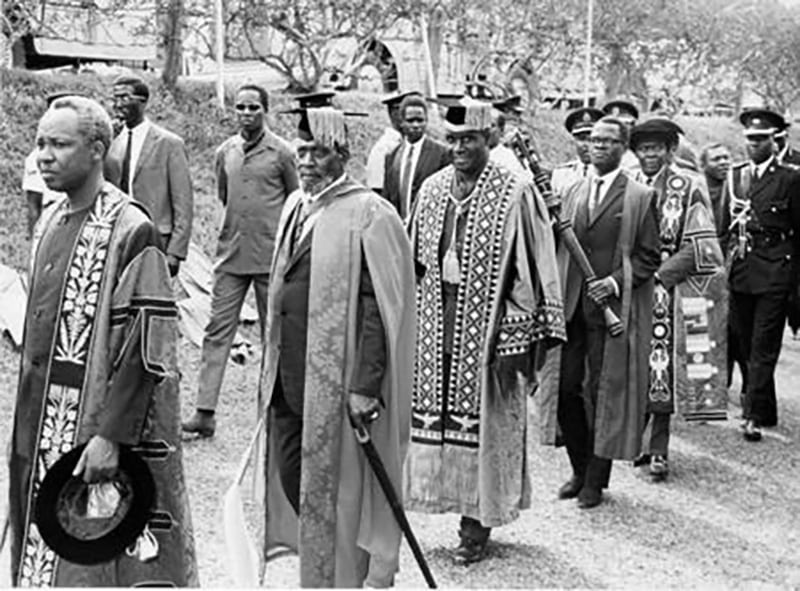

On December 9, 1961, Tanganyika became independent. The event was celebrated with a ceremony at the National Stadium. Soon, a law to restrict citizenship to Native Africans was presented to the Assembly. Julius Nyerere declared his opposition to the bill, likening its racialism tenets to the ideas of Hendrik Verwoerd and Adolf Hitler, and warned that he would resign if the bill were passed. In January 1962, six weeks after Tanganyika’s independence, Julius Nyerere resigned from his position of Prime Minister, determined to focus on reorganizing TANU and striving to chart a course for Tanganyika’s democracy. He retreated to become a backbencher in the parliament. He chose his close political associate, Rashidi Kawawa, to succeed him as Prime Minister. He travelled around the country, delivering speeches in villages and towns where he reiterated the country’s need for hard work and self-reliance. In 1962, Julius Nyerere was awarded an Honourary Doctor of Laws degree by his alma mater in Edinburgh.

During the first year of Tanganyika’s independence, the government largely concentrated on local problems. Under a government self-sufficiency scheme, villagers were urged to dedicate a day’s work each week to a community task, like building schools, roads, clinics, and wells. A nationwide youth service scheme known as Jeshi la Kujenga Taifa (JKT), meaning “army to build the nation,” was established to encourage the youth to participate in paramilitary training and public works. In February 1962, the government announced its plan to change the prevalent freehold land ownership system to a leasehold system. The government felt the leasehold system was a better reflection of the native ideas of collective land ownership. Julius Nyerere authored an article titled “Ujamaa,” which means “familyhood,” where he praised and explained the policy. He articulated many of his beliefs about African socialism in the article. Julius Nyerere believed that Ujamaa could be a source of a national principle that was different from the colonial period and would help strengthen Tanganyika’s independent path in the middle of the Cold War. After six months of independence, the government stopped the salaries and jobs of hereditary chiefs, whose posts were at odds with government authorities and were often considered too close to the colonial officials. The government also sought to Africanise the civil service. It gave severance pay to many white British members of the civil service and appointed native Africans, many of whom were not well trained, to replace them. Julius Nyerere admitted that such an affirmative action discriminated against Asian and white citizens but contended that it was a temporary necessity to correct the imbalance colonialism caused. By the end of 1963, almost half of the middle and senior-grade positions in the country’s civil service were occupied by native Africans.

In the course of the following year, many Britons charged with racism were evicted from the country. However, there were concerns about the absence of due process. Julius Nyerere justified the deportations asserting that Africans have been humiliated in their own country for many years and will not make them suffer now. The government closed down the Safari Hotel in Arusha after it was accused of ridiculing Guinea leader Ahmed Sékou Touré during his state visit in June 1963. The government also dissolved and appropriated the assets of the white-dominated Dar es Salaam Club after it refused to admit 69 members of TANU. Julius Nyerere personally stayed away from these controversies, which made some foreign media allege that the government was hypersensitive.

Formal oppositions to TANU’s government were in the form of two modest political parties. Zuberi Mtemvu established the African National Congress, which sought a more racist anti-colonial position, while foremost trade unionist Christopher Tumbo established the People’s Democratic Party. The government felt exposed, and in 1962, it introduced a law forbidding workers’ strikes as well as the Preventative Detention Law. This law allowed the government to detain individuals considered a threat to national security without trial. Julius Nyerere backed the measure citing similar laws in India and the United Kingdom, and stated that the law was needed to safeguard the government due to the weakness of both the army and the police. He expressed optimism that the government would never need to use the law and noted that they knew how it could turn into a favorable tool if given to a dishonest government.

The government formulated plans to draft a new constitution that would change Tanganyika from a monarchy that had the British Queen as its head of state into a republic with an elected president serving as head of state. The people would elect the President and then appoint a Vice President that would oversee Tanganyika’s parliament. According to a biographer, William E. Smith, it was already a foregone conclusion that Julius Nyerere would be chosen as TANU’s presidential candidate. In the presidential election held in November, Julius Nyerere defeated Mtemvu by securing 98.1% of the total vote. Following the election, Julius Nyerere disclosed that the National Executive Committee of the party had voted for the party to open its membership to all Tanganyikans. Only native Africans were permitted to join the party during the struggle against the colonialists, but Julius Nyerere now thoughts it should allow Asian and white members. He also specified that anyone removed from TANU since 1954 be allowed to rejoin in what he termed “complete political amnesty.” An Asian Tanganyikan, Amir Jamal, became the party’s first non-native member, joining in early 1963. A white man, Derek Bryceson, was the party’s second non-native member. Julius Nyerere accepted Europeans and Asians into his cabinet to ward off potential racial antagonism from these minorities. He saw it as an important step in building a national consciousness that goes beyond religious and ethnic lines.

There are two stages in colonial nations. The first is when midnight arrives, and the clock strikes, and you become independent. Fine. But after this begins an entire process of changing people and situations. I had been conversing with the people, letting them know that the second phase would not be easy… However, one thing must change after midnight – the colonial people’s attitude, the way they treat Africans as nothing. This has to change after midnight. The colonized are the rulers now, and the main street has to recognise this! If they’ve been spitting in his face, it must stop now! This cant take 20 years! We needed to drive the lesson home – Mwalimu Julius Nyerere on the deportation of white British people accused of racism

Tanganyika Presidency: 1962 to 1964

On December 9, 1962, one year after independence, Tanganyika officially became a republic. Julius Nyerere moved to the State House in Dar es Salaam, the old official home of the British administrators. Julius Nyerere did not like living in the building but stayed there till 1966. He appointed Rashidi Kawawa as his Vice President. He put forward his name to become the Rector of Edinburgh University in 1963. He vowed to travel to Scotland when needed; the position, however, was given to an actor, James Robertson Justice. He officially visited Algeria, Canada, Guinea, Nigeria, Scandinavia, and the United States of America. During his visit to the United States, he met President JF Kennedy. Though they liked each other personally, Julius Nyerere could not convince JF Kennedy to take a tougher position on the apartheid regime in South Africa.

The early days of Julius Nyerere’s presidency were largely busy with African affairs. He was in attendance at the Afro-Asian Solidarity Conference held in Moshi in February 1963. At the conference, he cited the latest Congolese situation to illustrate neo-colonialism, which he described as part of a second scramble for Africa. In May 1963, he attended the first session of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where he echoed his previous message that the embarrassing truth is that Africa is not yet liberated. Thus, Africa must take the mandatory collective steps to liberate Africa. He hosted the organization’s Liberation Committee in Dar es Salaam and gave weapons and support to active movements against colonialism in southern Africa.

Julius Nyerere Pan Africanism concurred with other leaders in Africa in terms of the idea of uniting the continent as a single country. However, he did not agree with Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah’s vision that it could be achieved quickly. Rather, he emphasized the need to create regional unions as short-term steps for the ultimate unification of Africa. Trying to actualize these ideals, in June 1963, he met with Ugandan President Milton Obote and Kenyan President Jomo Kenyatta in Nairobi. At the meeting, they agreed to unify their respective nations to form an East African Federation by the end of the year. However, this plan never materialized. Julius Nyerere lamented in December 1963 that the failure was the biggest disappointment of the year. The East African Community was instead inaugurated in 1967 to promote cooperation between the three nations. Julius Nyerere later saw his failure to create an East African Federation as his biggest career failure.

Julius Nyerere was bothered by happenings in Zanzibar, two islands located off of the coast of Tanganyika. He observed that Zanzibar was quite susceptible to the influence of outsiders, which in turn could affect Tanganyika. Julius Nyerere was keen to keep Cold War rivalries between the Soviet Union and the United States out of eastern Africa. In 1963, Zanzibar gained independence from the British Empire. In January of the following year, the Zanzibar revolution occurred. The revolution led to the overthrow and replacement of the Arab Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah by a government largely made up of native Africans. The revolution surprised Julius Nyerere. Like Uganda and Kenya, Julius Nyerere swiftly recognized the new government as legitimate. However, he allowed the dethroned Sultan to touch down in Tanganyika and jet out to London from there. At the asking of the government of Zanzibar, he sent 300 police officers to help restore peace on the island.

Facing Mutiny

Julius Nyerere stopped affirmative action employment in the civil service in January 1964. He believed the colonial imbalances had been corrected. He noted that it would be wrong to continue differentiating between Tanganyikans on any grounds except character and ability to carry out specific duties. Many trade unionists criticised the cessation of the policy, and it proved to be the catalyst for a mutiny in the army. On January 20, a small gang of soldiers from the First Batallion who called themselves the Army Night Freedom Fighters started an insurrection, demanding a pay rise and that their white officers be dismissed. The rebel officers left the Colito Base and entered Dar es Salaam and captured the State House. President Julius Nyerere escaped narrowly and hid in a Roman Catholic mission for two days. Oscar Kambona, a senior government official, was captured by the mutineers. They forced him to fire all white officers and install the native Elisha Kavana as the head of the Tanganyika Rifles. The Second Battalion in Tabora also mutinied with Kambona consenting to their demands for the appointment of the native Mrisho Sarakikya as the leader of the battalion. Having consented to a number of their demands, Kambona urged the mutineers from the First Battalion to go back to their barracks. Similar, albeit smaller mutinies erupted in Uganda and Kenya, with the governments of both countries asking for military assistance from Britain to suppress the uprisings.

On January 22, Julius Nyerere emerged from hiding. He gave a press conference on the next day where he stated that the mutiny had damaged the country’s reputation and that he would not ask for military help from the United Kingdom. He asked for military assistance from Britain two days later; the request was subsequently granted. On January 25, 60 British marine fighters were brought into the city in helicopters. They landed close to the Colito Barracks, and the mutineers soon gave up. Following the mutiny, Julius Nyerere dissolved the First Battalion of the army and expelled many soldiers from the Second Battalion. Concerned about the possibility of a broader dissent, Julius Nyerere dismissed close to 10% of the country’s 5,000-men police force and invoked the Preventative Detention Act in the arrest of about 550 people. However, most were quickly released. He criticized the masterminds of the mutiny for attempting to intimidate the country at gunpoint, and 14 of them were handed sentences of between five and 15 years in prison.

Officers of the Nigerian Third Battalion were brought in to keep order as the British marine fighters left. Julius Nyerere blamed the mutiny on the fact that his administration did not do enough to transform the army since colonial times. According to him, a few Africans were commissioned, and the uniforms were altered a bit; however, the top of the army still remained solidly British and could never be considered a people’s army. He acknowledged some of the demands of the mutineers and appointed Sarakikya as the army’s new commander and increased troop salaries. In the aftermath of the mutiny, the government became more focused on security, putting TANU personnel in the army and government-owned industry to strengthen party control throughout the nation.

The past week has been one of the most catastrophic shame for our nation. It will take months or even years to wipe away from the mind of the world the things ut heard about the events of the past week – President Julius Nyerere on the mutiny

Julius Nyerere Achievements – Tanzania Presidency

Julius Nyerere One Party State – Unification with Zanzibar: 1964

After the Zanzibari Revolution, Abeid Amani Karume made himself President of a single-party state and started the redistribution of Arab-owned land to black African peasants. Hundreds of Indians and Arabs left the island. Most of the British people living on the island also followed suit. Western powers were hesitant to recognise the government of Karume. In contrast, the People’s Republic of China, the Eastern Bloc and the Soviet Union did so quickly and offered help to the country. Julius Nyerere was annoyed at this Western reaction and the deeper failure of the West to acknowledge why black Zanzibaris had initially revolted.

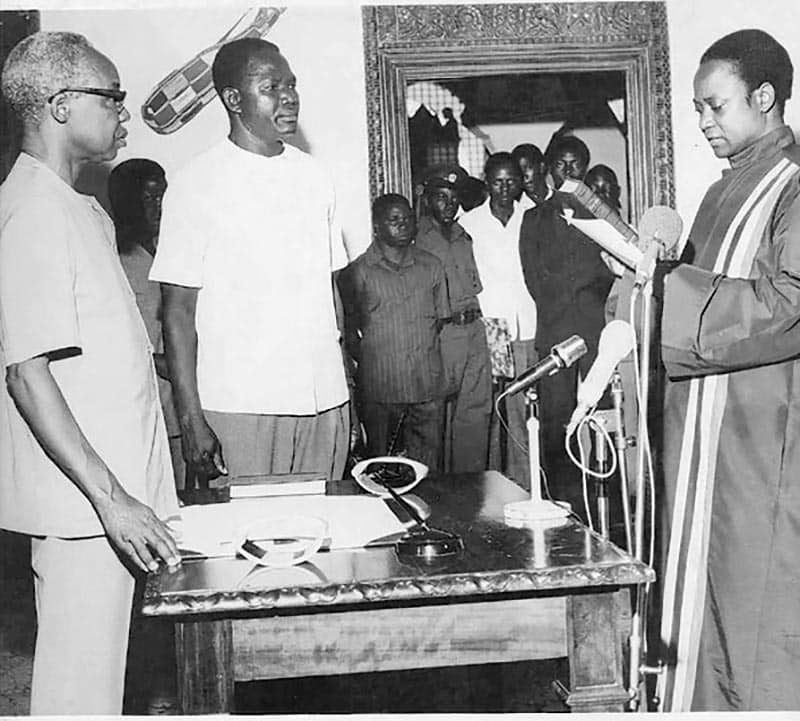

Julius Nyerere visited Karume in April. On the next day, they declared the political unification of Zanzibar and Tanganyika. Julius Nyerere dismissed insinuations that the unification had something to do with Cold War power tussles. He presented the merger as a reaction to Pan-Africanism. According to him, unity on the continent doesn’t have to come through Washington or Moscow. However, biographer William E. Smith suggested that an important reason behind Julius Nyerere’s eagerness to unify was to ensure Zanzibar does not fall into a Cold War proxy struggle as they have in Vietnam and Congo.

A provisional constitution of the “United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar” put Julius Nyerere forward as the president of the country, with Karume and Rashidi Kawawa presented as its first vice president and second vice president, respectively. The government commenced a contest to find the country a new name. Two months later, the government announced that the winning entry was “United Republic of Tanzania.” The structure of the government of Zanzibar was not immediately changed. Karume and the Revolutionary Council continued to rule, and the Afro-Shirazi Party and TANU were not merged. For many years, there were no parliamentary or local elections in Zanzibar. Zanzibaris constituted only 350,000 of Tanzania’s 13 million population, though, from 1967, 7 of the 22 cabinet posts were given to them, and they were directly appointed forty of the 183 parliament members. Julius Nyerere justified the unduly high representation by emphasizing the need to be sensitive to the national pride of the islanders. In 1965 he asserted that Zanzibaris are a proud community, and no one had ever planned that they simply become Tanganyika’s eighteenth region.

Abeid Karume was unpredictable and erratic. He repeatedly brought Julius Nyerere embarrassment. However, Julius Nyerere indulged him because of Tanzanian unity. In one of such case in August 1969, authorities in Zanzibar apprehended 14 men they accused of plotting a government overthrow. Mainland authorities had helped in the arrests. However, the arrested men faced trial in secret, and four of them were secretly executed, contrary to Julius Nyerere’s plans. Julius Nyerere was caused further humiliation by the habit of Karume and other members of the Revolutionary Council to force Arab girls into marriage and subsequently taking their relatives into custody to make sure they complied. Due to the rising international prices of cloves, Abeid Karume accumulated foreign exchange reserves to the tune of £30 million, which he kept away from the central government of Tanzania. Four gunmen assassinated Karume in April 1972.

Foreign and Domestic Affairs: 1964 to 1966

In the general election held in September 1965, the entire country voted in a presidential election, although Zanzibar was excluded from the parliamentary polls. Although the single-party system meant only TANU candidates could run, the national executive of the party chose multiple candidates for all seats except six, providing voters with some democratic choice. Nine backbenchers, six junior ministers, and two ministers were unable to retain their seats and were replaced. The two non-native members of the cabinet, Amur Jamal and Derek Bryceson secured reelection over black challengers. In the presidential election, Julius Nyerere ran unopposed, although there was ballot space to vote against him. Ultimately, he garnered close to 97% support.

Julius Nyerere’s Educational Ideas

Tanzania witnessed a rapid growth in population; the census held in December 1967 revealed a 35 percent population increase since 1957. The growing number of children made it more difficult for the government to actualize its universal basic education aim. Noticing that a small section of the population was able to get a high level of education, Julius Nyerere became concerned that they could form an elitist group separate from the rest of the population. In 1964, Julius Nyerere stated that certain citizens had huge amounts of money to spend on education while others had none. Therefore, the privileged ones are duty-bound to repay the sacrifices others made. Subsequently, in 1963, he made a two-year service in the JKT obligatory for every secondary school graduate. In October 1966, about 400 university students protested the directive at the State House. Julius Nyerere talked to the crowd and defended the measure. He then agreed to cut government pay, including his own. That same year, Julius Nyerere stopped using the State House as his permanent home. He moved to the newly constructed private residence on the Msasani seafront.

Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere Foreign Affairs

In August 1964, Julius Nyerere allowed four Chinese interpreters and seven instructors to work with the army for a period of six months, despite Western powers urging him to reject support from China, then ruled by Mao Zedong. In response to the disapproval of the West, Julius Nyerere remarked that most of the officers in Tanzania’s military were trained by the British, and he had recently signed a pact with West Germany for the training of an air wing. In the years that followed, China became the major recipient of Tanzania’s foreign relations. President Julius Nyerere embarked on an eight-day visit to China in February 1965. He strongly pushed the opinion that the socio-economic projects that moved China from an agricultural nation towards socialism were very relevant to Tanzania. Mao’s China fascinated Julius Nyerere because it upheld the egalitarian beliefs he shared. The government’s emphasis on the economy and frugality also inspired him. In June 1965, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai paid a visit to Dar es Salaam. China gave Tanzania millions of pounds in grants and loans and invested in many projects, including a farm implement factory, a radio transmitter, an experimental farm, and a textile factory in Dar es Salaam. After Western nations refused to help, Julius Nyerere got Chinese funding to construct a railway to connect Zambia to the coastline and through Tanzania.

In the early 1960s, President Julius Nyerere installed private phone lines to link him to Obote and Kenyatta. The lines were later removed in a cost-saving operation. Although Julius Nyerere’s desire for an East African Federation did not materialize, he still pursued better integration between Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. He co-founded the East African Community in 1967. Headquartered in Arusha, the community served as an administrative and common market union. Julius Nyerere penned an introduction for the 1967 autobiography of Kenyan leftwing politician Jaramogi O. Odinga titled Not Yet Uhuru. Julius Nyerere’s administration welcomed various freedom groups from the southern region of Africa, like FRELIMO, to set up their base in Tanzania to work towards deposing the white-minority and colonial governments of these nations. Julius Nyerere’s administration had friendly relations with Kenneth Kaunda’s government in neighbouring Zambia. In contrast, its relations with neighbouring Malawi led by Hastings Banda was poor. Banda had accused the government of Tanzania of backing ministers whom he claimed opposed his government. Julius Nyerere was strongly opposed to Banda’s decision to co-operate with the colonial governments of Portugal in Mozambique and Angola, as well as the white-minority governments in South Africa and Rhodesia. In 1967, the government of Julius Nyerere was the first to recognise the newly announced Republic of Biafra after it split from Nigeria. Despite the fact that three other African countries recognised Biafra, the decision put Julius Nyerere at cross purposes with many African nationalists.

Tanganyika had become a member of the British Commonwealth at independence. In September 1965, President Julius Nyerere threatened to leave the Commonwealth if the British government negotiated Rhodesia’s independence with the white-minority government of Ian Smith rather than with the representatives of Rhodesia’s black majority. After Ian Smith’s government singlehandedly announced independence in November, President Julius Nyerere demanded that the British government take swift steps to halt them. When the United Kingdom did not, Tanzania cut diplomatic ties with them. This action led to the loss of British help, but Julius Nyerere felt it was necessary to show that Africans would always keep their word. He emphasized that violence against British Tanzanians would not be condoned and that they remained welcome in Tanzania. Despite cutting diplomatic ties with them, Tanzania still collaborated with the United Kingdom in transporting emergency fuel supplies to landlocked Zambia by air after the Rhodesian government of Smith cut off its supplies. Uganda, Zambia, and Tanzania threatened to pull out of the Commonwealth in 1970 after British PM Edward Heath seemed to resume selling arms to South Africa.

Relations with the United States were strained as well. In November 1964, Oscar Kambona openly announced that they had uncovered proof of a USA-Portuguese plan to attack Tanzania. The United States embassy labelled the proof, which was made up of three photocopied papers, a forgery. After Julius Nyerere got back from a week-long trip to Lake Manyara, he conceded that this was possible. Julius Nyerere condemned the United States after it started Operation Dragon Rouge to rescue white captives held by insurgents in Stanleyville, Congo. He expressed anger that they would go to such lengths to salvage a thousand white lives while it did nothing to put an end to the enslavement of millions of black persons in the southern Africa region. He felt the operation was devised to reinforce Moise Tshombe’s Congolese government, which Julius Nyerere detested like many other African nationalists. Justifying his antipathy towards Tshombe, Julius Nyerere likened him to a Jew who hires former Nazis to invade Israel in his struggle for power, wondering how Jews would take it. U.S. relations reached rock bottom in 1965 after Julius Nyerere threw out two members of the United States embassy for engaging in subversive practices; there was no publicly produced proof to show their guilt. The United States retaliated by throwing out a councilor from the embassy of Tanzania in Washington D.C. Tanzania, in turn, summoned its ambassador to the United States, Othman Shariff, to return home. U.S.-Tanzanian relations gradually improved after 1965.

The Arusha Declaration: 1967 to 1970

Julius Nyerere attended a National Executive meeting of TANU at Arusha. At the meeting, he presented a new statement of party tenets known as the Arusha Declaration to the Committee. The declaration confirmed the commitment of the government to build a democratic socialist country and emphasized developing ideology and Julius Nyerere education for self reliance. Julius Nyerere believed that true independence was impossible as long as the state remained dependent on gifts and loans from other countries. It specified that more focus should be placed on developing the agricultural economy to guarantee better self-sufficiency, even if it meant sluggish economic growth. In the aftermath of the declaration, the Julius Nyerere socialism idea became fundamental to forming government policies. To popularize the declaration, groups of TANU followers marched across the countryside to make people aware. Julius Nyerere In October, President Julius Nyerere took part in one of those marches – an eight-day march that covered 222 kilometres in his native district of Mara.

A day after the Arusha Declaration, the government declared the nationalization of all banks in Tanzania, with indemnity paid to the owners. In the days that followed, the government announced its intention to nationalize many mills, sisal estates, import-export farms and insurance companies, as well as buying the majority share in seven other companies, including firms producing hoes, beer, cigarettes, and cement. A few international specialists were hired to run the affairs of the nationalized companies until an adequate number of Tanzanians had been sufficiently trained to take charge. Nevertheless, Tanzania’s civil service had little economic planning experience, and foreign companies eventually had to be ushered in to run many nationalized industries. One year after the initial nationalizations, President Julius Nyerere hailed Tanzanian Asians for the role they played in ensuring the smooth running of the nationalized banks. He stated that they deserved the country’s gratitude.

Julius Nyerere followed the declaration with some supplementary policy papers that covered sectors like rural development and foreign policy. “Education for Self-Reliance” emphasised the need for schools to teach farming skills. “Socialism and Rural Development” laid out a three-step course to create the ujamaa co-operative hamlet. The initial step was to persuade farmers to settle in a single hamlet, planting their food crops nearby. The next step is to create communal plots for the Tanzania farmers to explore working together. The third and final step was to create a communal plantation. Julius Nyerere was inspired by the Rumuva Development Association (RDA), a farming commune created in 1962. He believed RDA could be replicated across the length and breadth of Tanzania. There were supposedly one thousand Tanzanian villages calling themselves ujamaa by the end of 1970. Oftentimes, the farmers who moved into the new villages did not have the self-reliant energy that the RDA members had. Despite Julius Nyerere’s desire, villagisation did little to improve agricultural production.

The Arusha Declaration introduced a code of conduct for government and TANU leaders to act by. It prohibited them from having shares or serving as directors in private companies, owning any house rented to others or receiving more than one salary. Julius Nyerere considered these restrictions necessary to nip corruption in the bud across the country. He knew how corruption has become endemic in some African nations like Ghana and Nigeria and saw it as an impediment to his dream of African liberation. To ensure he personally complied with the measures, he sold his home in Magomeni while the local co-operative village in Miji Mwema got his wife’s poultry farm. In 1969, Julius Nyerere sponsored a bill to pay gratuities to ministers as well as area and regional commissioners; the gratuities could be used as their retirement income. The bill was not passed into law by the Tanzanian Parliament; this was the first time the parliament would reject a bill backed by Julius Nyerere. Most of the parliamentarians contended that granting extra funds to the officials went against the Arusha Declaration. Julius Nyerere chose not to push the issue any further, admitting that the parliamentarians’ concerns were valid.

Despite the domestic popularity of the Arusha Declaration, some politicians spoke up against it. In October 1969, a group made up of politicians and ex-army officers that included former Minister of Labour Michael Kamaliza and former head of the National Women’s Organisation Bibi Titi Mohammad were arrested for plotting to assassinate Julius Nyerere and overthrow his government. They were convicted and jailed. In 1969, Julius Nyerere went on a state visit to Canada. In the same year, Julius Nyerere told journalists he was considering retirement from the presidency with the hope that it would encourage the emergence of new leaders, although he had the desire to stay longer to see to the execution of his plans. In the election held in 1970, Julius Nyerere ran unopposed again and secured 97 percent support to serve as president for another five years. Again, Zanzibar was excluded in the parliamentary elections, with elections into the parliament taking place only on the mainland.

The Arusha Declaration was a watershed in the history of Tanzania and a widely powerful speech in the continent. The speech delineated the terms of political discourse in Tanzania and was widely popular in the country at first. However, there were dissenting voices – Paul Bjerk (Historian)

Julius Nyerere on Development – Economic Problems and Conflict with Uganda Between 1971 to 1979

Julius Nyerere’s administration sped up the villagization process in the early 1970s. They hoped it would boost agricultural productivity to allow Tanzania to export more. Through this, they can finance the development of light industries so that the country can produce more consumer goods and depend less on imported goods. Farmers that turned down joining communal hamlets were seen as TANU opponents. Police started rounding up farmers and forcefully moved them to the villages. Thirteen million persons were ultimately registered in 7000 villages. This development led to a severe disruption of rural production. A government survey conducted in 1978 showed that none of the hamlets met the official agricultural productivity targets. Many hamlets were left to rely on famine relief. Contrary to the intention of the government, food imports dramatically rose, and inflation grew. Total imports tripled in the 1970s while exports merely doubled.

The villagization process brought greater success in making social services more accessible to the public. Julius Nyerere’s administration worked towards the rapid growth of healthcare. The number of health centres increased by more than two folds, totalling 239, while rural dispensaries nearly doubled to reach a total of 2,600. The expansion was extended to education as well; by 1978, 80% of Tanzanian kids were in school. Tanzania was among the few African countries that had almost eliminated illiteracy totally by 1980. Embezzlement and bribery became more common in Tanzania throughout the ‘70s. An enquiry by the Tanzania parliament showed that government losses from corruption and theft climbed from Tzs10 million in 1975 to almost Tzs70 million in 1977.

The National Assembly, in early 1971, passed a law that authorised the nationalisation of all apartments, houses, and commercial buildings worth more than Tzs 100,000 except the owner lived in the building. This law was devised to nip the exploitation of real estate exploitation in the bud. The exploitation of real estate soared across much of post-independence Africa. The law further diminished the wealth of the Asian community in Tanzania, which had spent much to accumulate properties. In the months that followed, almost 15,000 Asians left Tanzania. Many media outlets started to complain increasingly about “parasites” and “kulaks,” which fuelled ethnic tensions towards Asian storekeepers. Catholic schools were also nationalised and made non-denominational by the government, a decision that angered many Roman Catholic Christians.

Julius Nyerere’s administration created a Ministry of Youth and National Culture to encourage the development of a distinct Tanzanian culture. The government wielded considerable power over the development of popular culture in the nation. It did this through organizations it created, such as the Baraza la Muzikila Taifa Music Council and Radio Tanzania Dar es Salaam. Comparing idealized rural ways of life to urban ways of life that were tagged “decadent,” Julius Nyerere’s administration, in October 1968, launched Operation Vijana to target forms of culture that were considered “decadent.” This included beauty contests, soul music, magazines and films considered inappropriate. In 1973, most foreign music was banned from being aired on national radio shows by the government. Julius Nyerere considered homosexuality an alien idea in Africa, and therefore Tanzania had no need to make laws against hatred of homosexuals.

Freedom of speech was largely guaranteed. Such that policies of the government were criticized in the press, within TANU and in the parliament. However, individuals considered to be political dissidents were still arrested without trial, usually in poor conditions. Rarely did Julius Nyerere personally initiate such detentions, although he had the ultimate authority on such arrests. According to Amnesty International, as of 1977, an estimated one thousand people were held under the Preventative Detention Act. However, the figure had reduced to less than one hundred by 1981. Kambona left the government in June 1976, apparently because of failing health. He subsequently moved to London. He later claimed to have been a victim of a plan to depose Julius Nyerere coordinated by a camp that opposed the Arusha Declaration. President Julius Nyerere was annoyed by the statements and demanded that Kambona returned. It was later exposed that Kambona took public funds to the tune of at least $100,000 when he left for Britain. He was accused of treason in absentia. Kambona had become disenchanted with Julius Nyerere by 1977. He accused Julius Nyerere of being a tyrant. In the years that followed, many Members of Parliament were thrown out for corruption and various crimes. The MPS, however, claimed that they were thrown out for opposing Julius Nyerere’s positions.

By the mid-‘70s, there were diverse speculations that Julius Nyerere would soon step down. In 1975, TANU nominated him to run for the presidency. In his speech, however, he cautioned against electing the same individual repeatedly. He talked about the Zanaki idea of kung’atuka, which implied that leaders pass on control to the younger ones. He also suggested that having TANU ruling the mainland while ASP ruled Zanzibar contradicted the idea of a single-party state. He, therefore, called for the merger of the two parties. The merger materialized in 1977, with the formation of Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), meaning “Party of the Revolution.” The de jure nature of Tanzania as a single-party state was guaranteed in the new constitution. Julius Nyerere started to promote Jumbe as his probable successor.

Abeid Karume was killed in 1972; his exit from power was a relief to President Julius Nyerere. Aboud Jumbe succeeded Karume. Julius Nyerere enjoyed a better relationship with Julius Nyerere. In early 1978, cabinet ministers increased their salaries. Students accused them of jettisoning the principles of socialism and started protesting. After clashes with the police, officials of the CCM asked the university authorities to dismiss 350 protesters, among whom was one of the President’s sons. Several members of Tanzania’s military started planning a coup in the late ‘70s. However, the plot was exposed before it could materialise, and the plotters were subsequently jailed.

Julius Nyerere made his second-ever state visit to the United States in 1977, where President Jimmy E. Carter praised Julius Nyerere as an elder statesman with unquestionable integrity. In Atlanta, he met with Afro-American civil rights fighter and widow of Martin Luther King, Coretta S. King, and together they visited her husband’s grave. Julius Nyerere stayed committed to supporting anti-colonialist movements throughout the southern part of Africa, including the ones fighting white-minority governments in South Africa and Southern Rhodesia, as well as the Portuguese colonial governments in Angola and Mozambique. The election that took place in Zimbabwe in 1980 led to a transition from a white-minority government to Robert Mugabe-led ZANU-PF government. Tanzania had been a long-term supporter of ZANU-PF, and Bjerk described it as a huge foreign policy win for Julius Nyerere.

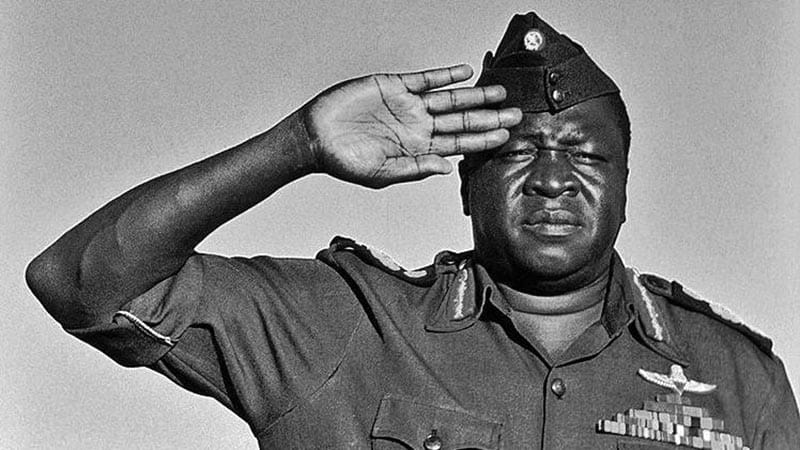

Rift with Uganda

An Idia Amin-led military coup in January 1971 led to the ouster of President Obote in Uganda. Julius Nyerere did not acknowledge the legitimacy of Idi Amin’s government and offered Obote asylum in Tanzania. Soon after the coup d’etat, President Julius Nyerere announced the creation of a “people’s militia,” a form of home defense to improve the national security of Tanzania. He also permitted banished Ugandans to build rebel camps in Tanzania. In response to President Julius Nyerere’s backing of Obote, Uganda blew up Tanzania’s Kagera Saw Mill in 1971. When Idi Amin threw out 50,000 Asian Ugandans in 1972, President Julius Nyerere criticised the move as racist. A boatload f Asian Ugandan refugees tried to dock in Tanzania, but Julius Nyerere’s government declined them permission due to concerns that it might stir up internal racial tensions. Having been notified of a purported plan by Idi Amin to oust him, President Julius Nyerere decided to permit followers of Obote to launch an offensive to overthrow Idi Amin’s government. From their base in Tanzania, Obote loyalists attacked Uganda in September 1972. However, they were crushed by the security forces of Idi Amin. Uganda retaliated by blowing up two Tanzanian border towns – Mwanza and Bukoba. Julius Nyerere dismissed his generals’ advice to counter with force. Instead, he settled for Somali reconciliation, which resulted in the signing of a peace treaty between Tanzania and Uganda. Nonetheless, relations between Amin and Julius Nyerere remained strained. Julius Nyerere permitted Ugandan insurgents to continue operating in Tanzania; he, however, implored them to lay low. The East African Community, which Tanzania had established with Uganda and Kenya, officially collapsed in 1977.

Uganda attacked Tanzania in October 1978 in what was later known as Kagera war and annexed the Kagera Salient. Julius Nyerere concluded that Tanzania’s reaction should not only be to repel the Ugandan forces back into their country but to attack Uganda and depose Idi Amin. To accomplish this mission, he mobilise tens of thousands of civilian soldiers to help the regular forces. Three Tanzanian regiments entered Uganda and levelled Mutukula. They slaughtered many civilians living there. President Julius Nyerere was horrified and ordered actions to make certain that the Tanzanian forces would not harm civilians in the future. He also persuaded foreign envoys to cut off weapons and oil supplies to Uganda. Over the months that followed, the Tanzanian forces made further advances into Uganda. Amin and many of his supporters ran into exile after the Tanzanian forces seized control of Kampala.

As the war raged on, Julius Nyerere was planning how to create a post-Amin administration in Uganda. Although Obote was still popular in Uganda, Julius Nyerere was warned by many other refugees not to restore Obote as president, mentioning how he alienated many sections of the society during his initial presidency. Julius Nyerere accepted the advice. Thus, he persuaded Obote not to come to the Moshi conference organised for exiled people in March 1979. The conference chose to support Yusuf Lule as a temporary replacement. Lule was announced president after the ouster of Amin. Not long after, he was booted out, and Godfrey Binaisa took over. Binaisa’s tenure didn’t last long either, with the general elections held in 1980 returning Obote as president once more. Julius Nyerere pulled out most of the Tanzanian forces and left only a small training force, despite Uganda entering a civil war cycle that lasted until 1986.

Tanzania spent almost $500 million on the war, causing further damage to its weak economy. There was a large-scale scarcity of consumer goods, which led to a spike in smuggling and hoarding, while several returning military men resorted to criminality. Tanzania’s Minister of Finance, Edwin Mtei, went into negotiations with IMF. In 1979, The IMF reached an agreement that Tanzania would be relieved of its debt in exchange for a programme of austerity measures. The measures include wage freezes, parastatal restrictions, relaxing import controls, and increasing interest rates. Julius Nyerere rejected the deal when Mtei brought it to him, seeing it as a denial of his message of socialism. Mtei subsequently resigned. Julius Nyerere regarded the International Monetary Fund as a tool of neocolonialism that imposed policies on poor nations to benefit their wealthier peers.

Final Term: 1980 to 1985

Julius Nyerere ran again as the presidential candidate of CCM in the Tanzanian general election held in 1980. He actively searched for a successor. One of his number one picks was the Zanzibari politician Seif Sharif Hamad, who he brought into the Central Committee of CCM. The relationship between Julius Nyerere and Jumbe became tense, and Julius Nyerere advised Jumbe to step down.

By 1985, Ali H. Mwinyi, a Muslim from Zanzibar, had taken centre stage as the front runner to succeed Julius Nyerere. Ultimately, Julius Nyerere agreed to support him. Mwinyi replaced Julius Nyerere in the general election held in 1985 after Julius Nyerere stood down. By doing so, A.B. Assenoh described Julius Nyerere as one of a handful of African leaders to have honourably, voluntarily and gracefully bow out of government. This action brought international respect to Julius Nyerere. He remained chairman of CCM till 1990 and vocally criticized Mwinyi’s policies from his position. Mwinyi wanted to liberalize the economy and removed a few of Julius Nyerere’s favourites who were against his reforms from the cabinet. The reforms caused inflation and currency devaluation, which destroyed many Tanzanians’ savings. Julius Nyerere viewed the reforms as a forsaking of his socialist model.

Julius Nyerere’s Modernization in Tanzania and Post-Presidential Activities

Julius Nyerere came back to the University of Edinburgh to appear at a conference on “The Making of Constitutions and Developments of National Identity.” He delivered the opening address, talking about post-independence Africa. Julius Nyerere was invited to preside over an international panel on the economic issues facing the “Global South.” He worked with future Indian PM Manmohan Singh on the panel.

Julius Nyerere resigned from his position as the chairman of CCM in August 1990. Before resigning as CCM chairman, he pushed for Tanzania’s change into a multiple-party democracy. He felt that the party had become corrupt and too hidebound that rivalry with other political parties would force CCM to sit up. His reflection on happenings in other socialist countries shaped his faith in reforms: the Eastern Bloc had fallen apart, Deng Xiaoping had presided over economic reforms in China, and Mikhail Gorbachev had engaged in glasnost and perestroika in the Soviet Union. Julius Nyerere noted that Tanzania could not remain an island and must take charge of its change and not wait until they are pushed. Hassan Mwinyi subsequently created the Nyalali Commission to explore the question of moving into a multiple-party system. The commission came to the conclusion that despite many Tanzanians wanting to maintain the single-party system, the country would profit from having competing political parties. Opposition parties like NCCR-Mageuzi, the Civic United Front, and Chadema emerged, with CCM remaining dominant. There was also an expansion of freedom of speech, with many new newspapers emerging.

The commission also recommended a change to a “three-government” federation, with both the mainland and Zanzibar having separate state governments in addition to the united federal government. The recommendation was intended to appease calls for the autonomy of Zanzibar, although Julius Nyerere did not support it. He contended that it would be a waste of taxpayers’ money as there wasn’t any proof to show it would make the government better. The government of Zanzibar, in 1992, entered the Organization of the Islamic Conference, a move criticised by Julius Nyerere on the grounds that the Zanzibari state had no business meddling in foreign affairs as it was an exclusive duty of the federal government. In 1993, fifty-five mainland M.P.s called for the creation of a regional government for the mainland. Julius Nyerere attacked the call in a flyer the following year. He delivered the nyufa speech in 1995, where he alerted the people about what he called “cracks” in Tanzania caused by separatism, tribalism, and corruption. He expressed worry about increasing mainland jingoism in response to Zanzibari separatism moves and contended that it would degenerate into ethnic rivalries and resentments. The recent Rwandan genocide where members of the country’s Hutu majority turned on the Tutsi minority influenced Julius Nyerere’s concerns.

He remained active in Chama Cha Mapinduzi politics privately and campaigned to make sure Benjamin Mkapa succeeded Ali Mwinyi as the party’s leader. He campaigned to support the party’s candidates in the 1995 Tanzanian election. Mkapa emerged victorious in the election. However, there were allegations of electoral fraud in coastal areas. In a speech, Julius Nyerere indicated his intention to quit politics altogether. All events signaled that the end of the Ujamaa philosophy by Julius Nyerere was getting reached.

Final Years: 1994 to 1999

Julius Nyerere stayed active in global affairs; he attended the 1994 edition of the Pan-African Congress in Kampala. He delivered a speech to mark the 40th independence anniversary of Ghana in 1997. In the speech, he indicated his renewed belief in Pan-Africanism and warned the continent against what he termed a “return to tribe.” He cited the increasing European unity within the E.U. as an example for African countries to copy. Late in the 1990s, he looked back on his time as president and noted that despite making mistakes, especially in the premature pursuit of nationalization, he defended the tenets of the Arusha Declaration.

After the elections of 1995, The U.N. called on Julius Nyerere to wade in as a negotiator to help put an end to the civil war in Burundi. The Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Foundation, through which negotiations would take place, was created. The foundation was modelled after the United States’ Carter Centre. That same year, Julius Nyerere presided over negotiation meetings between rival groups in Mwanza. Additional meetings were held in Arusha as well in 1998 and 1999. Julius Nyerere was resolute that a peace settlement should emanate from local initiatives rather than those drafted by Western powers. Julius Nyerere insisted on an inclusive process, with all political groups getting invites to participate in negotiation, irrespective of size. He also pointed out that creating political institutions was important to finding lasting peace in Burundi. The negotiations dragged on till Julius Nyerere died. Former South African President Nelson Mandela took up the mediator role after Julius Nyerere’s death. He made his last visit to Edinburgh in 1997. While there, he delivered the Lothian European Lecture and taught workshops at the university’s centre for African Studies. The army and the government contributed money to erect a house for Julius Nyerere in his native village. The house was completed in 1999, although Julius Nyerere spent only two weeks there before he died.

By 1998, Julius Nyerere knew that he was suffering from terminal leukaemia. However, he kept the information from the public. He travelled to England to seek medical care in September 1999. He was hospitalised at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London. While there, he suffered six major strokes in early October and was placed in intensive care. He subsequently died on October 14, 1999. He had six of his children and his wife at his bedside. The president of Tanzania at the time, Benjamin Mkapa, announced Mwalimu Julius Nyerere death on national T.V. and declared a 30-day period of mourning. Tanzanian state radio honoured Julius Nyerere by playing funeral music while his video footage was aired on T.V. On October 16, a mass of the dead took place at Westminster Cathedral. His body was subsequently flown to Tanzania, where they carried it past crowds in Dar es Salaam before taking it to his coastal residence. There, another mass of the dead was held at St. Joseph’s Cathedral. A burial was then held at the National Stadium, where hundreds of people walked past his body as it lay in state. His body was finally taken to Butiama and interred.

Julius Nyerere Political Thought and Ideology