The History of the East African Railways and Harbours – Tanganyika Road Service

The Beginning of the Central East African Railways

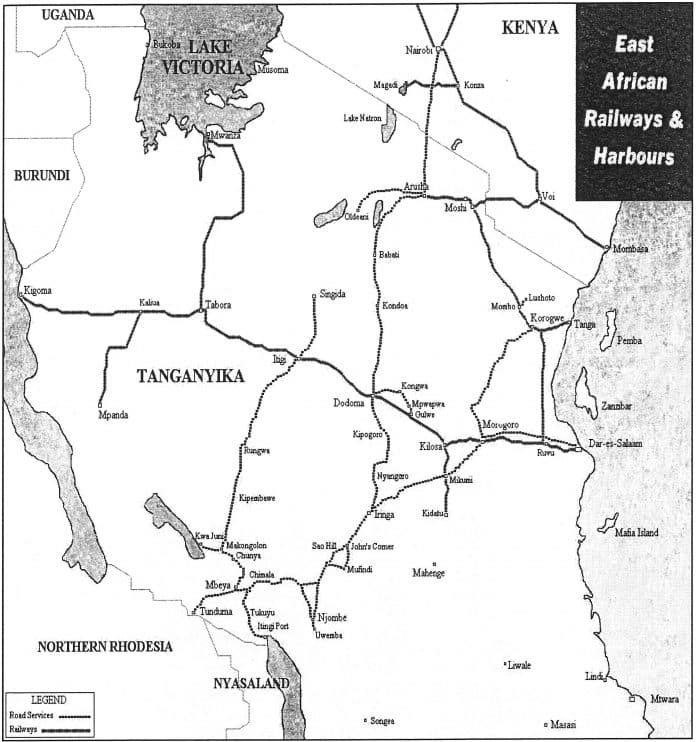

In October 1940 the Government of Tanganyika inquired the Tanganyika Railways and Port Services Authority to setup and operate a road service between Morogoro on the Central Railway to Korogwe via the Tanga Railway Line, a distance of about 178 miles. Tanganyika Railways and Port Services was required to establish this service due to lack of shipping and inconsistent shipments which often caused difficulties to transport goods between Tanga and Dar-es-Salaam. “This has proved to be a big success,” Mr Robins (General Manager at the time) wrote, “and taking into account the fall in transportation services in the area of the coast has impacted made a big impact. This service was an important part of transportation services by the end of the year. sSome obsolete equipment will be upgraded as options come up. “

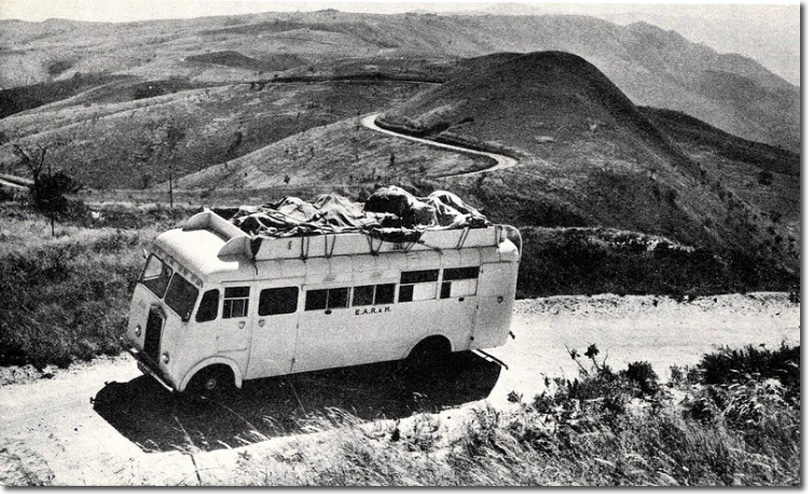

In 1942 the first class bus service, using 7-seat safari vehicles built on a 10-cwt chassis, came into use between Morogoro and Korogwe. The fares charged were twice the normal second-grade fare on a regular bus. The service was very successful and by 1943 the demand was huge, especially for military transport, so much so that all normal cargo was directed to the sea route between Tanga and Dar-es-Salaam – only their passengers and luggage were carried using the road.

East African Railway Master Plan

Expansion

In 1942 Tanganyika Railways and Port Services was again required by the Government to provide road services from Dodoma to the Southern Highlands. The service was launched on January 1, 1943. At that time there was a shortage of vehicles in Tanganyika and as a result the railways were forced to buy second-hand trains. Many were in poor condition of repair, there was a shortage of spare parts, roads were bad, drivers were not properly trained and there was a lack of suitable garage warehouses to conduct proper maintenance. With all these problems, by 1944 the service was able to carry not only regular passengers to and from the Southern Highlands but also a large amount of food for hunger relief, workers going to and from the sisal and rubber plantations and providing transportation assistance to refugee camps in the Southern Highlands. In year 1944 a road service was established from Mombo to Lushoto.

In 1944, as a result of the expansion of Road Services, NE Spencer was given the position of Assistant Superintendent of Passenger and

Freight Transport – an added title. In 1945 Stanley Martin was appointed Superintendent of Vehicle Transport Services Grade 1.

Between years 1946 to 1948 the Road Services continued to run under really challenging conditions as well as inadequate garage warehouses and unsuitable vehicles. Many of these vehicles had been purchased during the war, were overused and in poor condition. Although in 1948 the Road Transport Service had 250 vehicles, most were completely outdated and were waiting for their time to be removed from the road. But even though there were all these obstacles, the number of people and vehicles on the road increased, rates were kept at an acceptable level and revenues increased steadily. Large trucks with diesel engines were ordered, which later became the mainstay of road transport vehicles.

In year 1947 a new road service for passengers was established between Arusha and Dodoma, passenger and freight service between Arusha and Oldeani and when the Singida Railway was closed it was replaced by the road service between Singida and Itigi.

Development of the East African Railways and Harbours Corporation (EAR&H)

On May 1, 1948 Tanganyika Railways and Port Services joined with Kenya and Uganda Railways and Ports (KUR & H) to create what was known as the East African Railways and Harbours. The Headquarters of this new joint organization was set in Nairobi.

In Uganda, East African Railways and Harbours ran a small passenger and cargo service using the road between Masindi Port on Lake Kioga and Butiaba on Lake Albert, 75 miles away. Headquarters and garages, under a European Motor Transportation Officer, was in Masindi Town. The service got shut down in 1963 when water transport services at the Lake and Albert Lakes stopped due to the launch of the Soroti-Lira-Gulu railway connection.

Road Services Management

When East African Railways and Harbours created Road Services they were placed under the Mechanical Department. On May 15, 1950 the management of Road Services was transferred to the Department of Transportation (Chief Railway Supervisor). “The Vehicle Transport Officer was appointed for the direct supervision of the service but under the administrative control of the District Passenger and Freight Transport Superintendent, Dodoma, and directly accountable to the Chief Railway Supervisor on all technical issues. Its headquarters were set up in Iringa.

Then on January 1, 1952 the newly launched Commercial Department under the supervision of a Motor Engineer became in charge of all the road services. On January 1, 1955 central control was reinforced by the appointing of an Assistant Superintendent (Roads) at the Nairobi Business Headquarters. The Superintendent of Road Transport, situated in Iringa, was responsible for everyday operations. On October 1, 1966 the Commerce and Operations Departments were joined into the Traffic Department.

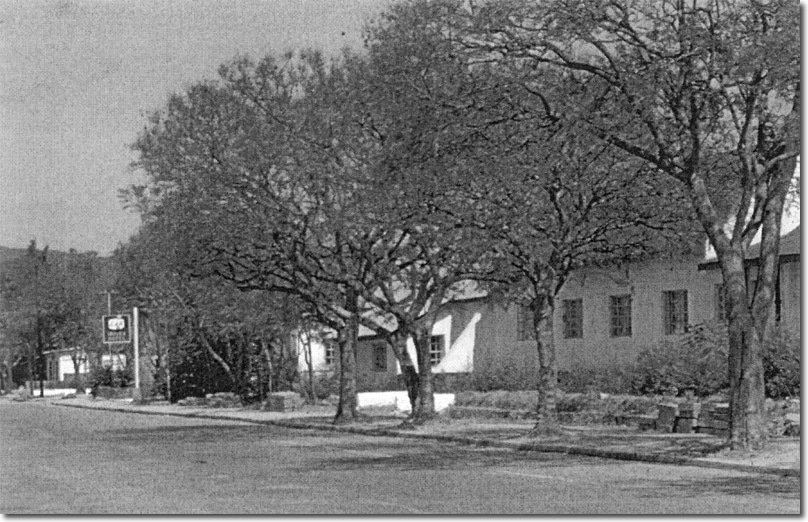

In 1950 my father was hired by the East African Railways and Harbours as a Mechanical Inspector and we therefore transferred to Iringa – from Nairobi where he was employed by Gailey and Roberts. I recall we spent approximately a week to reach there. We took the train from Nairobi to Kisumu on Lake Victoria, followed with boat to Mwanza in Tanganyika, another train to Dodoma, and in the end drove by car to Iringa. There was no place for our family and therefore stayed, along with several other white families, at the Iringa Hotel for 18 months until houses were constructed. We had numerous rooms at the side of the hotel but the amenities were very basic. For example, there was no electricity in Iringa even though the hotel had a generator: every evening a tractor was driven to the hotel and a large belt was connected from the tractor to the generator to be able to run it.

As per the documentation of his book, Driving Mad, Stan Pritchard (Traffic Inspector) remembers his first days in Road Services:

“I was standing in the middle of Tanzania (then Tanganyika before independence) carrying in my hand a jug that had been used in the army. Twenty or more African men stood in line to confront me. The next to come towards me was a Maasai warrior. He poked a spear into the ground, held it with his left hand, then with his right hand, tossed his robe in a reddish tinge to show his nakedness from the navel to his toes. Then, with great boldness, he began to urinate towards the jug.

“Inside it, not on top of it!” I yelled when the hot fluid was dripping allover my hands. The Maasai smiled, although my wise instructions given in my best Kilankasta accent clearly surprised him, he said cheerfully “Ndio bwana”. When the last few drops fell in the can I shouted “Next!” – and I began wondering how I had gotten into that environment.

I was not worried about doing this job, essential for the efficient operation of the East African Railways Services and Harbours Management branch, but I could not say, for sure, that I was enjoying it. The old beaten up bus, Albion brand, which I was traveling in got a radiator leakage and, as soon as all the reserve water he was carrying was spent, the driver had no choice but to use some more frustrating efforts. When he had lined up all the male passengers on the side of the road he gave me an empty can with the details of drawing all the liquid that could be found.

Even though I was fascinated by his action, I was not comfortable doing my part, but I had no excuse to deny. I was here, not long after leaving the UK, where I and nine others were sent to come support the East African Railways in year 1951, and I was on my way to Dodoma in Central Tanganyika, to take my place as the Road Services Inspector of Traffic in the District.

The distance of the main railway was approximately 600 miles starting from the east to west, whereby it connected the Indian Ocean port of Dar-es-Salaam with the local ports of Mwanza and Kigoma on Lake Victoria and Tanganyika. Many towns and villages scattered north and south of the railway were served, in the 1950s and 1960s, by numerous buses and trucks operating off the railways in Morogoro, Dodoma and Itigi to the Railway Services branch.

None of my fellow staff from the British Railways – all interested in the railways – wanted to do anything related to Road Services, but for me it was something I enjoyed. I had a brand new Austin A 70 truck dedicated to the East African Railway project, opportunity to drive around two thousand miles of jungle roads in Tanganyika, and to manage twenty stations that were old and a depots. I was so happy. My childhood dreams came true. “

Stan Pritchard also remembers how he was introduced to the drivers of the Road Services:

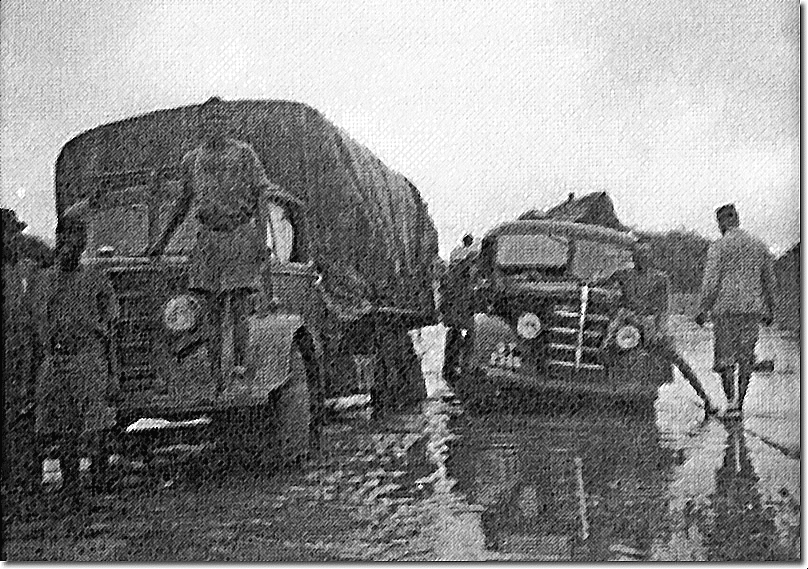

“… Within an hour a railway bus from our company showed up, and this was the answer to all my prayers at that moment. I could see in the back mirror, lights flashing, crawling forward rapidly through the mud and heavy rain without fear of anything like a ship facing a a storm on a watercourse connecting two seas.

With the help of a rope made of wired, a skilled, lively, and diesel bus driver with 120 horsepower, the car, and the L-mark were dragged down to the bottom of the pit – but with all the efforts i did with the steering wheel I could not make the car get out and back on the road. The bus driver stood up, got out of his room and, putting his hat back on his head, for a few long minutes looked all around the stuck car. Then, shaking his head – and I was waiting for a certain amount of knowledgeable pearl of wisdom to emerge – he went ahead and explained. In a voice of despair, and still shaking his head slowly, “Mbaya sana bwana,” was all he said.

‘Well that’s great help!’ I said to myself. “Look,” I said– “I see the same thing that it’s so bad but think, is there anything we can do about this?”

He took a moment to answer this question and then, with a big smile, said, “I know! I’ll take everyone out of the bus and they’ll pick you up. OK? This seemed like a very crazy solution but, before I protested, he opened the back door of the third class compartment and pushed into the rain all the passengers who were complaining – men, women and children, did not make a difference. “Suddenly, with a loud murmur and a loud crash, the whole car was lifted up and put back on the road.

I wanted to thank the passengers, who were now soaked, for their good efforts, but, before I could say a word, they disappeared and returned to the bus and closed the doors forcefully. However, I told the driver how much I appreciated all the efforts to solve the problem we faced and that I was going to put a good word at the head office to record this incident in his personal file. “Ahsante sana, bwana,” he said with a smile, clearly happy.

He was a good man but, being a good-natured inspector, I felt I had to make adjustments for the entire working time I had lost in that hole so, why not inspect this bus? I requested to see his certificates, and the number one thing I noticed was that the mail bags he was carrying were being sent to Kondoa Irangi, Babati and Arusha to the north, and this bus was going towards south to Iringa. Surely something was wrong? I inquired about the issue to driver, but he did not change his position. He said that all the time he was driving on the Iringa road and it is likely that the loading clerk in Dodoma had made an error with the bags which ended up in his bus. I therefore decided to check out the tickets passengers had, and this is where everything went down south. Passengers in the third class seats which were at the back of the bus, still wet and not amused to see me again, all were holding tickets to Iringa, but the three passengers who were waiting patiently in the pleasure of the ‘top class’ in front of the bus, had tickets to Kondoa Irangi.

We met three women who were young, they were all wearing crosses around their necks. They were new missionaries, they shared to me, having just left Europe on their way to their work station in Jver Africa – a missionary near Kondoa Irangi. They were very concerned about being late to reach their destination. “Sorry,” the older one said in a continental accent “do you think we can leave now. We are expected to arrive at the Kondoa Irangi bus station and we don’t prefer our hosts to get stranded waiting in this rain.”

“It is the fault of the dumb clerk who is issuing tickets in Dodoma,” the driver proclaimed. “I all the time drive to Iringa, and he is aware of that. He packed them with mail bags on an unwanted bus.” , but the story did not flow properly since the mail bags and the driver’s documents indicated that on the particular day, he was supposed to be heading to Kondoa Irangi and Arusha. While I was figuring out how to solve this small challenge, and as the three new missionaries became increasingly frustrated, another bus began to appear into our sight. This was obviously intended to go to Iringa, and not only did it have a few open seats in the third grade rows, but also the upper floor (first class) was completely empty. I decided to evacuate all third-class passengers from the Arusha bus and put them on the bus – but I did not attempt to negotiate for a lower price due to the ordeal that everyone just went through. It seemed that no one was interested in the empty third-class seats and, despite the small murmurs, the goats, chickens and passengers all crowded into the luxury of the first class compartment – but I had now already crossed the line of caring.

More confusion and worries got in to the missionaries, when, with the help of two third-class passenger buses helping to push and turned the bus around the opposite direction. “Where are we going?” they inquired.

With what I thought was a big smile I said, “Kondoa Irangi,” thinking that will calm them down. But it did not. When I saw the fear on their faces I felt the need to find more things to say. Although I was trying to avoid telling a lie, I shorten my clarification to only half the truth. “Kondoa is a few miles from where we are,” I explained to them, “there should be no worries, you will reach there, and i am very positive your hosts will not have to stay waiting for you for a long time.”

“Aha, dear!” was the oldest missionary’s reply, “Apologies if we missed our station and put you into all this mess. It is very noble of you to change the bus route for us and we can’t thank you enough. We will put you in our prayers – and God bless you.” gently and shyly, i went back to the dry area of my car. Despite the prayers of these good women, I was convinced that God could not bless me, let alone forgive me. I couldn’t blame him if he had prepared me for somewhere really hot at the end of my days on earth. And, with that horrible idea, I turned on the engine and resumed the fight with that slippery and muddy road on my journey to Iringa. “

In 1948 and Continued East African Railway History

By 1948 East African Railways and Harbours was running road services for passengers and freight combined the network that was 1686 miles long via these routes: Iringa to Mbeya, Iringa to Dodoma, Itigi to Mbeya, Mombo to Lushoto and Malindi, Itigi to Singida, Morogoro to Korogwe, Dodoma to Arusha and Arusha to Oldeani.

At the time which Les Ottaway (Department of Accounts) was working at the East African Railways and Harbours in 1948 there were no cars for staff, as a result all the time Les had to commute on the road, with his wife Margaret, he had to hitch hike for a ride, mainly in an old Bedford truck. Les, who currently resides in Upper Hutt, New Zealand, narrates the following story:

“It was a day that was dusty, hot and exhausting in 1948. We were just leaving Sao Hill in the Southern Highlands of Tanganyika early in the morning and by afternoon, we already passed the Chimala River, as we slowly and reluctantly climbed up the road with many turns and lots of holes in our old Bedford-type truck that was breaking down to wear and tear. With the engine that was hissing East African Railways steam locomotives sound and spitting we managed to reach the escarpment top and after stopping momentarily to let the engine cool down, we descended and circled for the last few miles into the small town of Mbeya and stopped quickly at the Mbeya Hotel.

The red dust and soot were washed away, we set into chairs at the hotel lounge drinking long cold drinks. It took an hour to forget the nine-hour torture from Sao Hill to Mbeya via the Njombe and Chimala River routes!

As we sat there, a long-haired man with red eyes and a khaki shorts that reached below his knee-length knees kept gazing towards our side. After a while he approached us not smiling with his face that looked like had took a lot of beating from the weather, he gave us an aggressive look and in a very unfriendly voice he asked, “Are you a cross?” we got agitated by his unwanted intrusion and to be honest we were both agitated after that long and exhausting trip.

I gave him a response, “My name is not Cross”, and started thinking, “why was he bothering to snoop around a business he should have not been into”. The old man spoke again, with an expression of relief on his face and this time he was a bit friendly, “I’m so sorry, I thought you could be Cross, Auditor of the Government. I required to meet him”, and with those words he turned his back on us and left.

It seems that we both had our wire crossed! “

At the end of the fourth quarter of 1949 to March 1950 vast regions of central Tanganyika were hit by severe drought. The government used Road Services to transfer large quantities of food aid from Dodoma to Iringa for distribution.

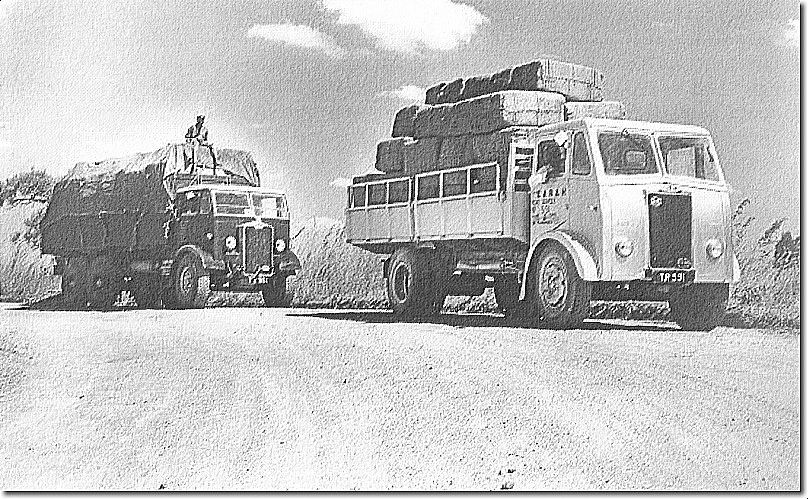

In year 1951, the government opened a new one story building at Itigi – which was the main link between the Central Railway and Road Services. Originally the lamps using kerosene was the form of lightning being used but the generators got connected in year 1953. Arthur Beckenham, in his book Wagon of Smoke, clarified Itigi: “Itigi is a connection of Road Services to Mbeya via Chunya, but with an exception of stations, garages, lodges with a few local houses there is nothing else around: it’s like a desert bush oasis. At this place I witnessed numerous 10-ton Albion trucks traveling 302 miles south to Mbeya through a mosquito-infested country. “

Road passenger and freight service went up by more than 10 percent between 1949 and 1950. As a result, vehicles had to be rented to facilitate passenger and freight forwarding and two trucks were transferred from Uganda Road Services to Iringa.

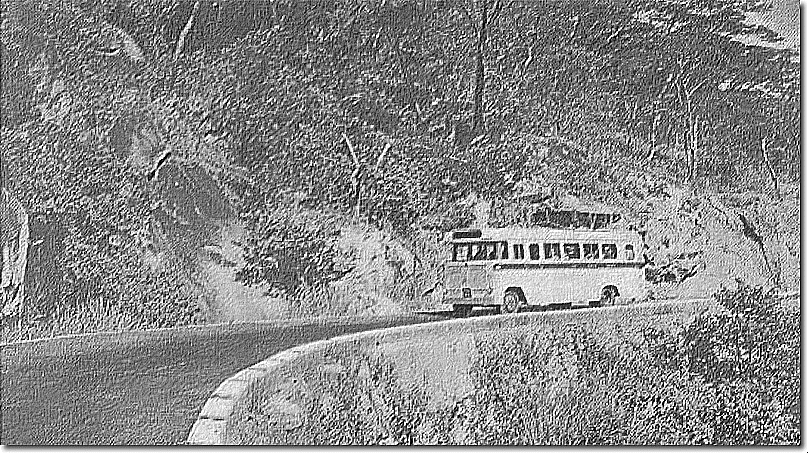

Until 1961 the network was constantly changing to meet the needs of passenger and freight transportation requirements, and competition increased as new railways took over some of the Road Service routes. As an example, in 1955 a new passenger bus service was launched to run from Nairobi to Arusha. When it reached 1961 the Tanganyika network had grown to a distance of up to 2,611 miles.

In 1954 new Road Service depots were constructed in both Morogoro and Mbeya and as a result major improvements were made to the Iringa depot.

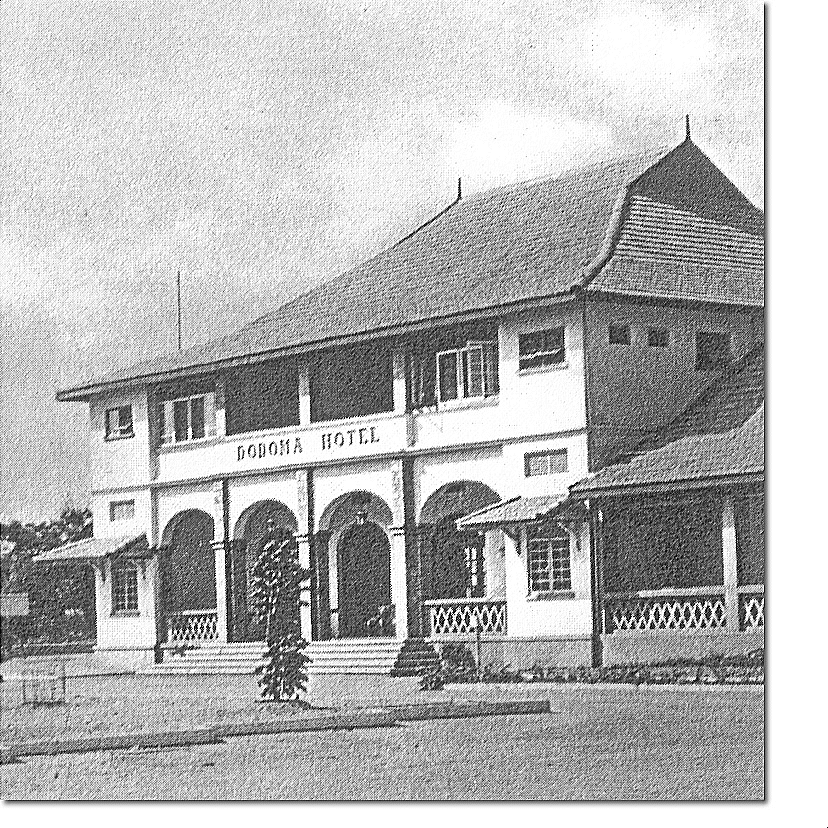

In March 1950 the Dodoma Hotel opened its doors. In 1955 the Iringa Hotel (with 24 bedrooms) was bought and in September 1955 the Mbeya Hotel also started operating.

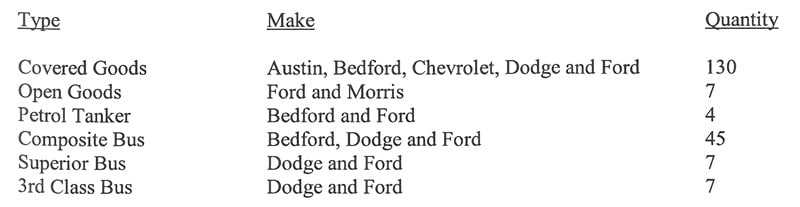

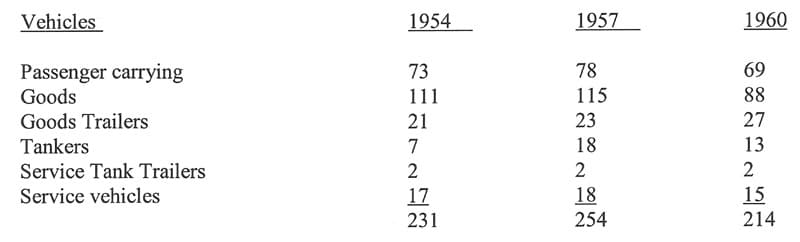

Group of Motor Vehicles Owned by East African Railways and Harbours

The vehicles were parked at garage warehouses all over Tanganyika and were being maintained by Asian and African workers supervised by a European Roads officer, who in 1956 was 25 but in 1961 had been reduced to 16 as there was an increase availability of vehicles that were working efficiently and improvement on the whole operation. The warehouses were Iringa (main garage), Mbeya, Itigi, Dodoma, Arusha, Morogoro and Korogwe. This group of vehicles was made back in World War II times and included a group of vehicles with engines that uses petrol various types with low capacity:

By 1953 new Albion cars which were using diesel engines were bought and this enabled a uniform maintenance plan to be used in all garage warehouses. My father played a major role in this initiative. All of this Albion policy was maintained and the differences in car groups from then on were only in terms of quantity:

Uganda has been included in the above table, whereby the Road Services were operating from Masindi Town to the lakes.

In 1951 my father supervised a fleet of 6 Albion trucks going to Johannesburg, South Africa, to build bus boards on them by Brockhouse Ltd. He led a motorcade on land through regions that were then called Nyasaland, Northern Rhodesia and Southern Rhodesia and had to stay away for six months. I remember the motorcade when it arrived back in Iringa – the excitement was so great that the whole city turned out to see it. He also came back with brand new bike for me! The first time drivers got to see traffic lights was in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia. Dad had told the drivers that they were supposed to pass when the lights were green and stop when they were red. One of the buses was in the middle of a busy intersection when the lights changed to red. The driver just continued staying there, just as he instructed! It took a while to resolve the confusion!

Frequently, during busy activities, private freight cars were rented to clear over accumulation of cargo. In year 1957, there was an additional purchase of 5 new Leyland Bulk fuel tanks (capable of carrying a mixture of 2,500 and 3000 gallons) which increase the number of vehicles to 18 – the original 13 fuel tankers had a capacity of only 1,500 liters. Fuel trucks were used to transport petrol and diesel from Dodoma (where various companies have large storage facilities) to gas stations all over the Southern Highlands. More fuel trucks were added to the already collection of vehicles in 1962 and 1963.

Road Conditions

In the 1950s road transport increased significantly and so the government invested in several new roads, for example, Iringa to Morogoro.

However, it was difficult and expensive to keep the road in good condition throughout the year. The roads were muddy, with small blocks covered with gravel or pebbles and with ruts, corrugations, and pits. Not only for a few miles, but for hundreds of miles. In some places the road was made of fine sand, in some places red clay (marble) or black clay. Dry clouds of dust generated from dry weather were dangerous and the heavy mud during wet seasons made transportation slow and unreliable. Bridges were built only on permanent rivers. The ones that only flowed during rain seasons had ‘bumps’ built on them – a flat piece of road concrete built about 1 foot and 3 inches above the base of the river. However, often these rivers were impassable because the water was usually deep and rapid.

Stan Pritchard explains the first time he drove on the roads of Tanganyika:

Shortly after arriving in Dodoma, the District Passenger and Freight Supervisor handed me the keys to a brand new Austin A 70, which I was to use in my inspection duties. He directed me to drive back along the Northern Highway to Arusha and conduct a thorough inspection of the depot there, as well as to visit and inspect the roadside stations at Kondoa Irangi and Babati.

Arusha, the northernmost reserve of Road Services in Tanganyika, was a lovely little town located 4,000 feet above the hills of Mount Meru and close to the majestic Mountain Kilimanjaro. It was a nice cool weather and I was looking forward to a nice day walk – but I wasn’t too excited about dealing with the rugged 280-mile dirt road and the stone road to get there. I had imagined the road as a passenger sitting comfortably on a tough Albion-type bus on the way there, but could not stop wondering about how would it be like to drive over that road on a weak car? And driving alone through a challenging alien area? And what if the radiator leaked? I would not have any male passenger in the car to provide fluid for repairs.

I don’t think the Director of Technical Services had any extra confidence in my driving ability than I had. He described at length some of the dangers of driving on rough roads in the Tanganyika jungle, such as over canyons and over impassable sand dunes, and his tendency to pull cars off the line and into dangerous slides. And in the heavy rainfall, when the roads turned into slippery mud, they were even more dangerous, he stressed. “Just remember,” he added, “driving here is not the same as traveling on British, or even Nairobi, paved roads – this is a permanent battle between you, a car, and any kind of surface crossing by road.”

With a pack of sandwiches and a full tea flask, and a stern warning from the Director of Technical Services not to exceed 30 miles per hour during the first 500 miles of driving, with his parting words “not to bend it” still sounding in my ears I began the journey.

Canyons on a wide section of a stone road just outside Dodoma hit and drove a car up and down in a concerning way. The tremors made me feel as if I were holding a pneumatic drill rather than a steering wheel, and even my head occasionally jumped high enough to hit the roof of the car. The car felt like it was crashing and, even more disturbing, I couldn’t make it go in a straight line. It was a terrible situation to have a car that always slipped from one side of the road to the other.

Fortunately, when jumping back and forth caused my foot to slip and hit the paddle to the floor of the board, I found a way to deal with the situation. The car increased its speed for a few seconds and, almost miraculously, the tremors ceased. With a small amount of spiritual guilt, I deliberately stopped following the direction of the Technical Services Director, pushed my leg down harder, and increased the speed to 35 miles per hour. Of course, progress was a bit smooth. Encouraged by this, I crawled up to 40 miles per hour and then – feeling very guilty – even up to 45 miles per hour. With this great careless speed the steering wheel felt as weak as a pneumatic drill; the rear wheels weren’t jumping too much out of control and my head wasn’t hitting the roof and I felt a little relaxed – but not too much.

Although hitting and jumping up and down decreased slightly, the car was still slipping all over the place but now, to my horror, the slopes were even more difficult to control. The car swerved to the side for a moment and slipped at full speed almost in a 90 degree fashion to the road. This was worrying as I was forced to turn my head further and further around to see the road, not through the windshield, but now through a side window. It was so bad, and I had to do something about this situation, otherwise I felt like I would soon be traveling on the road backwards – and I really couldn’t turn my head any further! Through painful experience of trying and making mistakes, I quickly learned to not apply the brakes and instead just lift my leg from the accelerating pedal, then, gently and very slowly, turn the steering wheel and try to force the car to stay in a straight line. It took a lot of concentration, and I had a few exciting moments when I occasionally made excessive adjustments to the bushes along the road but, slowly, I began to master the challenges.

With increasing confidence, and with the Director of Technical Services’s instructions on driving forgotten for a short while, I began to enjoy the challenge and excitement of slipping over rough pebbles in the fastest race. It was fun – but soon a terrible problem arose. A crushed log pillar appeared. There was no ‘delay’ or ‘argument’ about this matter. In large faded letters it said, quite clearly, “Slow down – Speed Causes Corrugations”. This was a blow, but I faithfully obeyed. Once again the steering wheel began to shake and the car shook and flew back and forth forcefully and uncontrollably. It seemed to me that my slower speed was making the bumps worse. So, being divided between obeying the law and keeping the car intact, I chose to keep the car in one piece. And I learned later, from an engineer in the Department of Public Works, that the signs were a great ‘deception’ nonetheless. He told me that a lot of research had been done on the occurrence of corrugations – but no one had found the answer, and there was little evidence that speed was the source. So I kept going.

The road slowly changed from wide and rocky to narrow, with many corners and dust, and bumps connected to potholes. This caused a variety of problems for me. Frequent tremors and slippery slopes made room for a little easier driving, but it was interrupted by shocking bumps whenever the wheel hit one of the potholes – and the potholes were so large that it was almost impossible to avoid them all. Worse was the feeling of helplessness, and all control of the steering wheel was lost, whenever the front wheel slipped into one of the deep cracks that sometimes passed through the middle of the road.

After several hours of this situation I felt so relaxed, seeing a huge baobab in front of me I stood in its shade and began to unwrap my sandwiches. ‘This is life’, I thought, ‘fresh air, sunlight and open space’. Even if the road sections had this challenge it was much better than working in an old railway office in the northern industrial area in the UK. I was suddenly awakened from my joy to see monkeys emerging from some of the rocks along the road and sitting there watching me eat. I, an animal lover, threw a piece of sandwich on him, and the other monkeys appeared quickly. I tossed them more pieces of sandwiches and enjoyed watching their funny actions as more and more monkeys did and fought with each other for sliced bread and canned meat. They were having more fun than I was, I thought.

The car was quickly surrounded by a road full of arguing monkeys. At first it was fun, but it was a problem when I wanted to go back on my journey. No amount of honking or threatening ‘intrusion’ and waving my hand from the window moved them. I was a little scared, but I was too scared to get out of the car to drive them away. When one gentle monkey jumped on the bonnet, and stared at me through the windshield I hesitated even to drive to the group. I didn’t want to hurt or upset them, and I certainly didn’t want to get to Arusha with an angry monkey or two still sitting on a bonnet holding on to the wipers. So, with all my might, I opened the door forcefully, bent down, and picked up a large stone from the road. ‘Okay’, I thought, ‘if you want to be stubborn then I can be tough too’. With those words I threw the stone in the middle of the crowd. Most of them were scattered, but one older monkey, older than the others, had other ideas. He lifted the stone and, at an astonishing speed, jumped into the car – and threw the stone at me! I cringed when, in a loud, irritating voice, a stone struck the front of my new shiny car.

When I returned to Dodoma a few days later the newest car in the railway car was carefully inspected by some old experts at the garage to see if this inexperienced man brought to Tanganyika’s dusty roads had managed to drive on the road. They looked at the small, but clearly visible place, and shook their heads knowing what had happened. When the Director of Technical Services arrived and examined the damage, I was given a detailed talk on how to control a car in unruly areas, and was told that inexperienced and easily deceived young people, like me, should especially learn how to drive again and again. when they go out to the African roads.

“But Sir” I said – this was a time when one was expected to call his superior ‘Sir’, and indeed the lords were present in the British Colonial Service, and before that there were no ‘Ladies’ in those high positions – “the part that was dented was not caused by me “.

“What do you mean, ‘it has nothing to do with you’? You’re the one who was driving or not”?

When I came up with the simplest answer, “the monkey threw a stone at me”, the garage manager pointed out that I was more stupid than I appeared, and I heard him clearly say softly, “We have one right here!” But the Director of Technical Services was more reasonable.

“Look here boy”, he said, somewhat mercilessly I thought. “If you continue to make any such stupid comments you will find yourself on the next boat to the UK, and back to the British Railways.”

I got a picture that I had not gave myself a very good start in my career in Road Services in Tanganyika. “

In Wagon of Smoke, Arthur Beckenham recalls the journey by bus he made in September 1950 from Dodoma to Iringa and then to Mbeya and Tukuyu:

Wednesday. 13 Sept. (Road Service) At 09.20 we left the convoy, 20 minutes late, a 6-ton Albion truck leaving, carrying letters and luggage for two miles ahead of the others: and two passenger buses (Bedford). An Albion truck was given this 2 mile headway due to road dusty conditions. The leading reason is that if the truck breaks down the letters would be picked up by one of the buses. As soon as we left the city of Dodoma we entered a stretch of road full of potholes and corrugations on the Northern Highway Road …. at 44 Miles, a small slope at an average of about 3,000 feet! Immediately after 82 Miles a small slope is reached followed by a descend down the plain of the Great Ruaha River. The twin-span bridge, painted with new aluminum paint, can be seen for miles before being reached. From 155 Miles the road slowly climbs to Iringa, which is about 5,200 feet ! Ten miles before Iringa you pass through Nduli Airport, one runway crosses the road, and we were stopped when the East African Airways flight took off. Iringa is surrounded by mountains in a beautiful setting and the main road is lined with beautiful mauve jakaranda trees along it. The evening temperatures were extremely low and a wood fire was lit on the hotel’s lounge fireplace.

Thursday 14 Sept’s trip is 187 miles to Chimala. Our lunch center was located at the Highlands Hotel in Sao Hill, in an open country that resembles the Scottish Moors. During the day we crossed the Mbarali River and passed 1awa where gold is mined. Now we were following in the vicinity of the Uporoto highlands.

The Chimala Hotel, where we arrived at 11.05 pm, has a main building with a lounge and dining room, while the private rooms are small white circular houses with thatched roofs, the entire section is set in a garden of lemon trees and vines, the high mountains of Uporoto in the vicinity of the rear. From the balcony of the living room one could look north for forty to fifty miles beyond the Buhoro Flats.

Friday 15 Sept. Thirteen miles after leaving Chimala we began a steep climb over the Uporoto range. The 220-mile to the summit is 7,500 feet. We arrived in Mbeya, a place that looks like a Swiss mountain village, at 5.10pm.

Saturday. 16 Sept. We visited Tukuyu, 47 miles south, traveling on a very dusty road. The southern tip of my trip. Part of the trail was on the other side of the Uporoto range, with a beautiful view of Mount Rungwe (9,700 feet). The District Commissioner’s fort was the former German fortress, and the bridges and thick walls looked very strong. After returning to Mbeya, I explored the city. In the evening I met Mr. K. Menzie6 The English founder of Mbeya, was a living history book. “

Other Risks

In addition to natural hazards other incidents occurred involving wildlife and swarms of bees, but perhaps one of the concerning event is which involved a snake as reported in June 1954 East African Railways and Harbours Staff Journal:

“Unwanted Journey Partner. An unusual and unpleasant experience befell a truck crew between Dodoma and Iringa recently when a 5-foot-tall snake fell onto the vehicle from a hanging tree. A Road Service Supervisor who was called used smoke bombs that made the snake go over the engine cover, where it disappeared. The snake later appeared on the car’s front but once again disappeared. The next morning the truck driver managed to kill the snake with a knife.”

Theft and loss of luggage at Road Services was a problem and in 1955 a concerted effort was made to address this problem on the worst route – Itigi to Mbeya (304 miles). Stan Pritchard was made responsible in resolving this challenge and he recalls:

“In the mid-1950s the Headquarters in Nairobi was concerned about the increase in compensation rates we were paying at the expense of the Itigi-Mbeya route, but things got worse one day when we lost a large consignment of gold mines from the gold mine called “Saza”. The police was not finding a resolution in their investigation of the robbery, or any previous robbery incidents, and, desperately, the Director of Technical Services (Quentin More at the time) Instructed me, “come out of that b… …way and do not concern yourself with coming back unless all the theft incidents are resolved!” And i obeyed – I was no where near Dodoma and Iringa for several months, never touched there not even once.

Basically I discovered how the fully closed doors of our trucks could be removed without disturbing the seals, and that an amazing truck came down from Tabora from time to time and met, in the middle of the night, with some of our drivers at Rungwa. Using civilian-dressed soldiers from the Mbeya Police Station, and after setting a trap to the suspected drivers to drive that night, I planned an ambush at Rungwa to arrest them all in the act of robbery. As we hid in the bushes on the side of the road, a herd of elephants disturbed us and the ambush had to be abandoned. We did not arrest anyone, but we must have scared them so much that later the incidents of theft decreased significantly.

A day or two later I was sleeping in a government house in Itigi and in the morning I was told by a freight clerk that the railway car, waiting to be unloaded, had been broken into the night and many valuables had been stolen. This made me think that something like that could happen while I was there, so I quickly drove to Manyoni and obtained a search warrant from the District Commissioner there, with the help of his Asian police inspector, to search every shop in Itigi. We found nothing, except one store that was still closed. We were told that its owner had gone to Singida on an Arab-owned bus with a ‘heavy’ load. So we went to Singida and searched the city for an Arab-owned bus. We found it very late at night parked outside an Asian house with a scary appearance. Since my search warrants were not valid in Singida, I approached the local white police chief for help and planned a raid on the house at about midnight. Not only did we find all the stolen goods, but also the Asian who was the head of the Itigi station! He was supposed to be absent from work due to illness, which is why I had not seen him the day before. However, it seemed that the case was open and close issue and the supervisor had told me that I would be required to appear in court as a necessary witness at a later date. From then on we had only a small problem with theft.

As my foreign vacation drew to a close, and as the case did not seem to be brought to court, I was getting concerned – the Singida police chief always had a valid excuse every time I asked. Eventually our headquarters in Nairobi took the case to the Police Headquarters in Dar-es-Salaam. As a result, the Singida police chief was convicted of accepting bribes to keep the case out of court. “

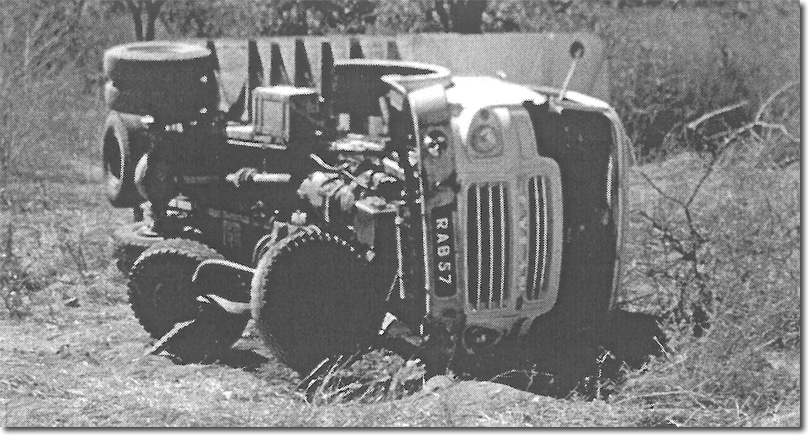

Passenger and freight transport accidents were a common occurrence. A copy of the report prepared by Doug Golding on a fatal accident can be found below along with the following report of the causes of deaths.

Convoy Supervisors

In the very early days of the Road Service vehicles used to operate in caravans with a convoy supervisor traveling in the last vehicle. He carried a few spare parts, like fan belts, water pipes, etc., and a toolbox. This system was quickly abandoned as something that did not save money in car time. After loading, the trucks had to wait until all the others were loaded and ready to go: then they left together, all arrived at the same time and, again, had to stay in place without a specific purpose waiting for their turn to be unloaded. The system was slowly abandoned and the Convoy Supervisors were given Land Rover vehicles that were used to patrol the road to assist vehicles in need. That too was eventually abandoned as an expensive luxury that could be avoided.

Passenger and Freight Transport

Despite road conditions Road Services transported tons of goods, and in later years revenues were more than operating costs:

However, not all passenger and freight transportation generated revenue, as Stan Pritchard discovered on the Mbeya – Itigi Road:

“Slowly I collected a lot of newsletters. Mostly was general information that was basic, … Other information, such as when, and in what place, some trucks seemed to be inconsistent with the information shown in the logbooks of those trucks.

Whenever I found one of our trucks during the day I would sit next to it in the back and observe, unseen, for a few minutes before stepping back and allowing myself to get lost in its cloud of dust. One incident which i drew the line with this procedure is when I came to the back of a truck carrying passengers. This was a lucrative business for some of our drivers who charged each passenger below the normal bus fare. It was not uncommon to find twenty or more passengers sitting up in a dangerous position, on the front of the car, on a canvas covering a load on a fully loaded truck, and often holding small children with chickens and, at times, even goats. . This was very dangerous, and especially if the driver drank illegal alcohol in one of the huts and thought that he could get back on schedule by speeding and run the truck on all corners happily. This had to be stopped and I went all the way for it in a big way. I stopped every truck I saw and removed all the illegal passengers, and from time to time drunks threatened to bring violence, often putting myself in danger but, almost always, I appeared as someone who was not liked by the driver as well as the passengers. But it had to be done. All the while the drivers were watching me. If I had evidence of their involvement in the robbery they were fired from the service. If they were only carrying illegal passengers they were dropped off and given small cars for short trips and, as a result, losses in salaries.

This exercise began to slow down and I rarely saw a truck carrying passengers until, one day as I closely followed the truck during the day, I thought my eyes were cunning me. The canvas cover was moving in an unusual way. It would slowly come up and then change its position to a different place, so I stopped the truck and ordered the canvas to be removed. Beneath it, blinking and winking at the sudden heat, they were half a dozen Africans. It may not have been as dangerous as climbing on top of the truck load, but the heat and the stench in the air must have been something unhealthy and very uncomfortable. But what made me even more concerned was the great opportunity that this event provided for the snatching, while unseen, from the goods that were being carried. Any other time later when I got to situations like this I just played a kind of quick Irish dance on the canvas, and listened to the squeaking sounds. I think I can claim success, theoretically, to get rid of these practices. It is not surprising that the bus passenger and rates began to increase and I was pleased to see details of this issue provided by statisticians at the Nairobi headquarters who researched these issues.”

Road Service License

In 1957 the Government of Tanganyika introduced a road service license administered by the Legal Transport Licensing Authority and all East African Railways and Harbours passenger and freight services had to be licensed in the same manner as any other operator. This authority was very focused on the financial situation and the relevant quality features of the applicant vehicle. By 1959, the General Manager was able to report that “control of passenger service schedules implemented by the Transport Licensing Authority in Tanganyika continued to be effective in calculating passenger transport services on East African Railways and Harbours routes.“

Change of East African Railways Map Route

In January 1961 a major review of the future of Road Services was conducted. In recent years the services have become increasingly

competitive and revenues have generally been reduced by operating costs, including refurbished items. It was also necessary to consider the connection of the Ruvu-Mnyusi railway line built to connect the Central and Tanga Railways. The decisions that came out were that the Dodoma – Kongwa – Gulwe service should be closed immediately, the Itigi – Singida passenger service should be closed at the end of the year and as soon as the new Ruvu – Mnyusi link starts operating, the routes from Morogoro – Korogwe and Dodoma – Arusha – Nairobi should be closed.

The service between Itigi and Singida (75 miles) which had been operating since 1948 was phased out in late 1961.

Following the death of the Tanganyika Groundnut Scheme and the closure of the Kongwa branch in March 1956 a new road service was established between Dodoma, Kongwa, Mpwapwa and Gulwe, 89 miles away. By 1961, however, passenger transport and cargo on this route had been reduced to a non-profit level, and services were removed.

On April 1, 1957 the Morogoro to Iringa road was opened for heavy trucks. This was part of the process of establishing Road Transport Licenses. The outcome was the reintroduction of passenger and freight transport across the Dodoma railway and upgraded transport times between Dar-es-Salaam and the Southern Highlands.

In September 1962 the Kilombero Sugar Factory opened at Kidatu and the Roads Service carried the factory’s products until the opening of the Mikumi to Kidatu railway branch on June 1, 1965.

The Strike

In 1960 the African Union of the Tanganyika Railways called on its members to strike, over a wage dispute, for 82 days from Tuesday 9 February to Saturday 30 April. Road services were severely disrupted and continued only because Europeans, Asians and some African workers drove the vehicles. Some services were canceled, such as bus service from Mombo to Lushoto. During school holidays the only services that worked were buses to take children to / from various boarding schools in Tanganyika. I remember one time my father was driving a truck, on a caravan, with Bob Cluett to Morogoro. They decided to take a break, and when my father stopped the car on the sidewalk, the surface broke apart and his car got stuck. He was not loved! In Iringa, the wives of the railway workers kept the Iringa Hotel working. It was a matter of everyone working because there was so much work to do. Eventually the strike ended.

The End

On December 9, 1961 Tanganyika gained independence and on December 9, 1962 it was part of the Commonwealth as a Republic. On April 26, 1964 it joined with Zanzibar and formed Tanzania.

With the formation of the East African Community in 1969, East African Railways and Harbours was divided into two organizations, the East African Railway Corporation and the East African Ports Corporation. Railway headquarters were established in Nairobi and Ports in Dar-es-Salaam. However, the East African Community collapsed in 1977 and the Tanzania Railways Corporation (TRC Tanzania) commenced on 21 October 1977, taking full responsibility for the services previously provided in Tanzania by the East African Railways Corporation (EARC). These services included railways, road services, maritime services, hotels and food preparation and distribution.

Since the early 1990s TRC has been undergoing a restructuring process that involves the gradual removal of its non-core services. As a result, Road Services have been closed, hotel and food preparation services have been given to private companies and a separate company ‘Marine Services Company Limited‘ now offers maritime services in Lake Victoria and Tanganyika. TRC currently only operates rail passenger services and freight services.

If you enjoyed this article, explore our other post “History of Rail Transport in Tanzania (Mainland)” for a full overview of railway transport in Tanzania.

For more articles about Tanganyika click here!

Estimated reading time: 41 minutes